| Resources | Ufo | Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce History | Lost Chords ]

|

[ Projects

| News | FAQ

| Suggestions | Search

| HotLinks ] | Resources | Ufo | Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce History | Lost Chords ] |

Prayers to the people of Bertie Country:

Reports Of Fatalitites In Bertie County - News Story - WCTI New Bern

- April 16, 2011

BERTIE COUNTY -- We are receiving reports of a tornado touchdown in

Bertie County between Askewville and Colerain.

Tornado unleashes fury on Askewville The Roanoke-Chowan News-Herald

- April 17, 2011

ASKEWVILLE – Shocking.

That’s the way most people in Askewville and the surrounding community are describing the devastation left in the wake of tornadoes that ripped through this central Bertie County town Saturday evening.

Bertie County Tornado Victim Quick Action & Prayer Saved Our Lives - April 17, 2011

The devastation in the town of Colerain in Bertie County is something even fire chief Milton Felton couldn't believe when he saw it. "I didn't think it would be this devastating. I saw this twister from my house and I started riding and I was on another road and found people pinned up under the house."

Liberty Hall - Captain Edward Outlaw Indian Woods Windsor

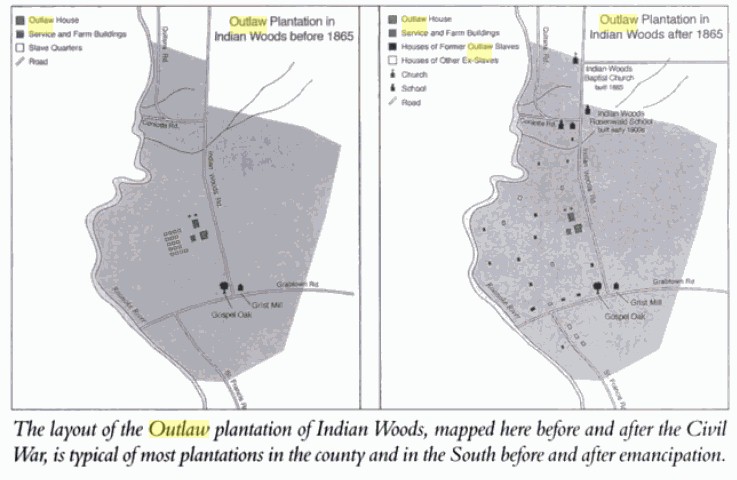

Bertie County: An Eastern Carolina History By Arwin D. Smallwood

"One of the largest and most prosperous plantation in the Windsor Township during the antebellum era was the David Outlaw Plantation of Indian Woods"

About "David Outlaw's home in Indian Woods. The son of Ralph Outlaw, David served Congress from 1848 to 1852. Though destroyed by fire, David's home was located across Indian woods road from the home of his son Edward, who was a captain in the Confederate army during the Civil War and sheriff of the county after the war. Edward's house still stands."

"By the close of the war in 1865, white and black residents of Bertie County had fought and died for BOTH sides."

"Other former slave holders, such as Edward Outlaw, Whitmell Sharrock and William Grimes, who were respect for their fair treatment of slaves, found huge numbers of ex-slaves asking to work and live on their farms following emancipation."

The

"Outlaw House" or "Liberty Hall"

in Windsor, Bertie Co., NC, off now SR 1108 at the corner of Indian Woods Rd.

and Grabtown Rd.

Liberty Hall is a majestic, but mostly unnoticed, historical home located just outside of Windsor on Indian Woods Road.

The house was once the home of Captain Edward Outlaw and is listed on the National Register and is being renovated. The exterior of the house is a rare example of the Italianate architecture and the interior is trimmed with Greek revival woodwork. The house was built in the 1850's by Lewis Bond. Bond and his family moved to Tennessee and the house was sold to his sister and her husband, Mr. and Mrs. John Peter Rascoe.

They gave the house to their daughter, Lucy Rascoe, soon after her marriage in 1868 to Captain Outlaw.

Tradition maintains that a Northerner, S.L. Pennoyer, was the contractor for the house and that it took three years to complete. Pennoyer is buried in the Rascoe family graveyard that is near the house.

Edward Outlaw was born in 1840 in Bertie Co. After the death of his parents, his uncle, Col. David Outlaw, became responsible for his care. The colonel was a member of the legislature and was a United States Congressman from 1848-1850.

Capt. Outlaw attended the University of North Carolina before enlisting in the Confederate Army, serving in Company C of the 11th NC Regiment. He came through the war without a scratch although it was said that he would charge the enemy at a moments' notice. After the war, he returned to Bertie Co. to serve as a commissioner, a state representative, and a sheriff. He died in 1921 at Nags Head and was buried in his Confederate uniform.

He, his wife, and two of their 10 children are buried in the cemetery of St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Windsor. Liberty Hall has remained in the family through the years. The present owners are Carlton and Lucy Gillam of Windsor. She is a descendent of Captain Outlaw's wife.

The "Outlaw House" or "Liberty Hall" in Windsor, Bertie Co., NC, off SR 1108 at the corner of Indian Woods Rd. and Grabtown Rd.

...some time after the Jan. 26, 1920 Bertie Co. Census) Millie Gurley White Phelps, and at least the two oldest children, lived in a small out building at what is now called the "Outlaw House" or "Liberty Hall" in Windsor, Bertie Co., NC, off now SR 1108 at the corner of Indian Woods Rd. and Grabtown Rd. Her aunt Millie Bazemore Early (wife of David C. Early, who died in 1916) was living in the "Outlaw House" with nephew Drew E. Bazemore on the Jan. 26, 1920 Census. Millie Gurley White Phelps was in Bertie Co. in Sept. 1920 when son, Joseph, was born, and Nov. 1922 when son Archie was born

2330 Indian woods Road. Windsor, NC

Liberty Hall is a majestic, but mostly unnoticed, historical home located just outside of Windsor on Indian Woods Road. The house was once the home of Captain Edward Outlaw and is listed on the National Register and is being renovated. The exterior of the house is a rare example of the Italianate architecture and the interior is trimmed with Greek revival woodwork. The house was built in the 1850's by Lewis Bond. Bond and his family moved to Tennessee and the house was sold to his sister and her husband, Mr. and Mrs. John Peter Rascoe. They gave the house to their daughter, Lucy Rascoe, soon after her marriage in 1868 to Captain Outlaw.

Tradition maintains that a Northerner, S.L. Pennoyer, was the contractor for the house and that it took three years to complete. Pennoyer is buried in the Rascoe family graveyard that is near the house.

Edward Outlaw was born in 1840 in Bertie Co. After the death of his parents, his uncle, Col. David Outlaw, became responsible for his care. The colonel was a member of the legislature and was a United States Congressman from 1848-1850. Capt.Edward Outlaw attended the University of North Carolina before enlisting in the Confederate Army, serving in Company C of the 11th NC Regiment. He came through the war without a scratch although it was said that he would charge the enemy at a moments' notice. After the war, he returned to Bertie Co. to serve as a commissioner, a state representative, and a sheriff. He died in 1921 at Nags Head and was buried in his Confederate unform.

He, his wife, and two of their 10 children are buried in the cemetery of St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Windsor. Liberty Hall has remained in the family through the years. The present owners are Carlton and Lucy Gillam of Windsor. She is a descendent of Captain Outlaw's wife.

Restoration of this great house is under way, and the owners have tried to keep as much of the original structure intact as possible. The house has three floors. The first is the basement floor. The floors on this level had to be torn up when the renovations started. When the floors were torn up, a layer of plaster was found underneath. Footprints of pigs and dogs could be seen in the plaster, where the animals had evidently tracked through the plaster during the original construction of the house. The walls on this level are brick and they serve to support the rest of the house. The interior of the house on the top two floors have 14' ceilings. The corner beams are all solid from the ground to the top of the house. The plastered walls in most of the rooms have been knocked out, but in the hallway and around the stairs, it is still intact. In the hall at the entrance of the house, one can see where a huge chandelier would have hung. Tradition says that dances were held in the large hallway of this house. All of the mantels on the fireplaces in the house are original. There are 12 fireplaces and two chimneys. The doors on the closets are original and inside the closets there are still some of the hooks on which 19th century clothing hung. The banister on the stairway is constructed of solid walnut and is still in excellent condition. Work on the exterior is almost complete. There is a large porch on the front and one on the back.

Near Liberty Hall is Bertie's GOSPEL OAK, a silent reminder of the days when traveling preachers came through and members of the community gathered under this tree to hear religious sermons. Traditional word of mouth stories about this tree have been passed through the years. Tradition says this tree was also a meeting place for the Indians and the whites.

Liberty Hall is the last remaining house in a neighborhood of six majestic

homes. (The Bryans of "Snowfield", the Clarks, and the Pugh, and the

Smallwoods all had plantation homes here in Indian Woods) The history and

preservation of this house and others like it are essential to the education and

culture of the Roanoke-Chowan area. The house is not open to the public for

viewing, but visitors can ride by and enjoy the beauty of this old home."

Outlaw Farm Road. Windsor, NC - Google Maps

More information regarding Outlaw Farm Road from Mr. Speller:

Outlaw Farm Rd.

The farm was part of Edward Ralph Outlaw's Plantation Estate left to him by his father, Edward Cherry Outlaw. David Stanley Outlaw was his uncle and not his father as has been record by some other researchers. David Stanley Outlaw was the brother of Edward Cherry Outlaw and became Edward Ralph Outlaw's guardian upon his father's death.

Edward Ralph Outlaw had a son, James Outlaw, in 1858. When James Outlaw married about 1878 or 1880, Edward Ralph Outlaw deed him most of that tract of land that you see and James Outlaw acquired the rest and also cleared some of these tracts for farming.

James Outlaw also acquired tracts of land in the Indian Woods area that has belonged to the Outlaws. Rascoes, Bonds, Coopers, and Smallwoods. I have been told by relatives that James Outlaw owned more than 2,500 areas of land when he died in 1925.

James Outlaw married Malinda Mitchell. One of their children was Maggie Outlaw. Maggie Outlaw married Turner R. Speller. My father, Benjamin F Speller, was their son. Some of James Outlaw descendants still own parts of this farm and other land in the area. Others sold their shares of this farm to my cousin, Dr. Horace Ward, who is also a Bond and Speller descendant as am I.

The James Outlaw Family Cemetery is located on the right hand side of the Outlaw Farm Road in the slight curve near the end of the road shown on the map.

Here is a web address that will provide more information about my relationship to the Outlaws, Bonds, Spellers and others in the area.

Outlaw - Dr. Benjamin Speller - great grandson of James Outlaw - Benjamin F. Speller, Jr., Ph.D.

David Outlaw - 14 September 1806 – 22 October 1868) was a Whig U.S. Congressman from North Carolina between 1847 and 1853.

Born near Windsor, North Carolina in 1806, Outlaw attended private schools and academies in Bertie County. He graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1824, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1825, opening a practice in Windsor. A member of the North Carolina House of Representatives from 1831 to 1834, Outlaw was a delegate to the state constitutional convention of 1835.

From 1836 to 1844, Outlaw was solicitor of the first judicial district in North Carolina. In 1844, he was a delegate to the Whig National Convention, and was elected as a Whig to the 30th, 31st, and 32nd U.S. Congress (March 4, 1847 – March 3, 1853). He was defeated for re-election in 1852, but was elected to the state house once again in 1854 and 1858. After leaving Congress, Outlaw returned to his law practice and died in Windsor in 1868, where he is buried in the Episcopal Cemetery.

David Outlaw was the cousin of Congressman and state senate speaker George Outlaw.

David Outlaw Papers, 1847-1855; 1866. - description of archival material held in the Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

| Size | About 375 items (1.0 linear foot). |

| Abstract | Whig congressman from Bertie County, N.C. Chiefly correspondence of Outlaw to his wife while he was a member of Congress, 1847-1853. Subjects discussed are state and national politics, including the Mexican War, the slavery question, sectionalism, the Wilmot Proviso, the Missouri Compromise, and the Compromise of 1850; social life in Washington, D.C.; and Outlaw's family and his farm in Bertie County, near Windsor, N.C. In his absence from home, Outlaw's farm was managed by one of his slaves. Also included are a few letters from Outlaw's wife and daughter and genealogical material on the Outlaw and Anderson families of Tennessee (typed transcriptions). |

| Creator | Outlaw, David, 1806-1868. |

Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives

Mf. 362

-- David Outlaw Papers, 1847-1866. 326

items. UNC. 1 reel. 35 mm. Microfilm Only

Collection.

These are papers of David Outlaw (1806-1868), Congressman, lawyer, and Whig

political leader from Bertie County, North Carolina. The collection consists

primarily of his correspondence to his wife Emily, written while he was serving

in Congress, 1847-51. Outlaw comments on social and political life, the Mexican

War, internal improvements, slavery and compromises, and the 1848 presidential

election. Many prominent individuals of the period are mentioned including John

Q. Adams, Henry Clay, Andrew Johnson, and James K. Polk. Also included are

letters dealing with family problems and the hiring out of Negroes, and

genealogical data on the Outlaw and Anderson families.

Microtext Collections in Political History at MTSU Library - Middle Tennessee State University Library

David Outlaw Papers MFM 219David Outlaw: This Hollow Hearted Sodom

In January 1849, David Outlaw took his place in the U.S. House of Representatives. A new congressman from Edonton district, North Carolina, he had been chosen to represent the people during a grave political crisis. The war with Mexico was over, and a half million square miles of territory (not including Texas) added their generous portion equally to the United States and to the dilemma over the expansion of slavery. This subject, Outlaw admitted, constituted the "everlasting topic" of debate before the Assembly. "We dream of negroes, hear nothing else by the wayside or in the House [or] at our meals."

The galleries were packed with gawkers; the representatives were packing pistols. Ultras on both sides postured and preened for their constituents and the crowds, "fan[ning] the flame and increas[ing] the excitement." To the hoopla and the harangues, the moderate Outlaw brought a rare moment of calm reflection. "Day after day the evils of slavery…are paraded for our entertainment," he said, "by men who know nothing" of the South. But the Southern representatives are themselves barely above "braggadocio and abuse." "To expect men to agree that slavery is a blessing social, moral and political," Outlaw declared, when most Southerners "do not believe it and so far from believing it, believe exactly the reverse is absurd."

"It is sufficient," he concluded, "to deal with [slavery] as an existing fact, one for which we are not responsible and which we must treat as practical men."

This level-headed assessment was not part of any speech he made, however; sitting on the floor of the House, with the country crashing down around him, Outlaw had tuned out the Assembly, and scribbled these words to his wife in his daily letter home.1

* * *

David Outlaw married Emily Turner Ryan on June 7, 1837. Though she was a widow and mother of two, David felt no remorse that he would not be "the object of [her] virgin affections." David was himself 31, comparatively old for a first marriage, and he felt he had "none of those graces of manner" that attracted the opposite sex.

Awkwardly tall, he stood a bony six-three, with red hair, fair skin, and thick glasses. "I am not a handsome man," he admitted to his wife, and "though blessed with ordinary sense, I am not a brilliant man in conversation or otherwise." Outlaw's nearsightedness had made him aloof, more awkward; his world was the smaller one that lay within his immediate compass. Somehow, though, Outlaw transformed it all into a kind of cultivated coolness, a removed hauteur. "I do not think I am a very vain man," he summed it up precisely, "because I am too proud a man to be so." Given all his failings of physique and character, Outlaw found it a wonder that he should be loved at all-but he was, and by all appearances deeply.

Ten years into their marriage, the Outlaws' letters still gushed with

affection. When he was away from her, David wished he could "travel by telegraph" or, "like the genie in the lamp," be transported to her bedroom where Emily would awake to "find a man in bed with you, imprinting kisses on your mouth and neck & bosom." Emily was similarly smitten: "your love is to me," she assured him, "worth more than all the rest this earth contains."2

But the Outlaws' relationship, while emotionally close, was burdened by physical distance.

David spent up to eight months of the year in Washington and another two as a circuit judge in North

Carolina. This left him just two months to spend with wife and family, and those not usually in a row. While the Outlaws' love was undoubtedly genuine, absence threatened always to dull it, to abstract it into something less lived and felt than reflexively constructed in empty words. Emily found the loneliness particularly acute during her pregnancies, and when David did not come home as promised for the birth of their second child, she suffered bouts of deep despondency. She could not understand why he would willingly trade a life of domestic bliss, one which he claimed to prize above all else, for the hollow-hearted company of strangers. In time, however, fatigue and compromise guided even the long absences into a steady rhythm as much a part of the Outlaws' marriage as anything else. "I fear the time will never come for you to [return home]," Emily wrote her husband typically, "for I see plainly that you are to be a candidate next year. While I see no chance for us ever to live together again, I will never ask you again not to be a candidate & will pray for resignation to my lot in life." Complete resignation, of course, never came, and could not be expected. Emily's society, and indeed Emily herself, understood the worth of a woman as centered not only in her character, but in those of her husband, her family, and her marriage. David's absences were part of his eminence and thereby her eminence-but if extended too long or exercised too brazenly they could easily become part of her humiliation. Trying to convince his wife that his conduct was not unusual, David reminded her of several representatives who never went home, hanging around Washington during the intersessions or luxuriating at the latest spa. In her reply, Emily used the example to make a more general case for the domestic failings of politicians as a class, only barely excepting her husband from the profile. As exasperated as she became, however, Emily always came at the problem obliquely, humorously. Partly she did so because she recognized the limits of her power to change things-but mostly she did so because she understood her love for her husband, and his for her, as the most worthy and ennobling parts of her life. "You cannot know how eager I am to get your letters & how I read them over & over again," she told him, "& you never can know, my own dearest, how very precious your assurances of your love are to me. They cheer me in sadness & afford me food for pleasant thought in my loneliness.…Without [your love] I could not live."3

The feeling seems to have been quite mutual. Never fully engaging Washington's social scene or even his own duties as representative, David Outlaw threw himself into his correspondence home, composing at least one long letter every day, often penning them right on the floor of Congress. "Do you not think," he wrote Emily, "[that] you were mistaken when you said [that] I should be [too] absorbed in politics…to find time to write you?… I have almost persecuted you with letters.…I venture to say without knowing how the fact is that no man in Congress has written his wife so often as I have." More amazing, though, than the prodigious quantity of David's output was the energy he expended ensuring that in formulating and reformulating his devotion to wife, home, and family, he never became formulaic. Unlike other politician-correspondents, David Outlaw never sought refuge in the vague and vainglorious language by which men of the period justified their conduct; he never evaded requests from home to help his wife build a love lived and felt, a love as effortless and as involuntary as breathing. Indeed, though the couple's present was filled with absence and longing, David was careful to write in rich detail about his memories of the past and his hopes for the future, making as concrete as mere words ever can feelings that might become abstracted over time and space. Temporarily housed in a hotel room the Outlaws had shared on their honeymoon, David allowed his pen to gambol through the pleasant recollections. "On such a night," he wrote his wife, "a person's thoughts wander back to when the heart was fresher, the affections…less selfish than contact with the world makes them.… [Tonight] I could almost fancy [that] you were eighteen and that I was twenty-five." Fueled by such thoughts, he claimed, "the romance and poetry of youth revive and burn [and], for a short time at least," the Outlaws could fall in love all over again. It was not just the past that gave the their relationship its vibrancy, however. "Just think of it," David wrote Emily after they had been discussing their oldest daughter Harriet.

"We shall soon have a grown daughter…and you will be called the old lady and I the old gentleman. It almost makes me sad to think of it." Despite the long miles that stretched between them, despite fouled and slow communications, hurt feelings and occasional disagreements, the Outlaws compensated for not having a present by crafting a love out of the memory of being young and the hope of growing old together.4

The capital, however, was no place for a dedicated husband and family man. Socially awkward among the rough company of men, David spent most of his evenings alone in his boarding room "reading documents and newspapers," writing letters and franking paperwork to his constituents. Such tedium was made all the more unbearable by the fact that when he finished "ten to one if some bore [who] is prowling about" did not pop in on him. "You know it is not my forte suddenly to contract intimacies and friendships," he told his wife. "I cannot make a friend of every new unfledged acquaintance or give my confidence to an acquaintance a day old. This is probably a misfortune, but I cannot help it." Washington, though, was a city that thrived on ephemeral friendships and vapid posturing; it was a land of boisterous make-believe in which alliances rose and fell in a stew of self-interest and whim. Unable to function on this social level, David had "scarcely an individual in Washington" whom he could "look upon as a friend" and "not one to whom" he "could unbosom" his "thoughts and feelings." Moreover, even if he had developed such a friendship, he would not have been able to share the best of what he understood himself to be, a devoted husband and loving father. "I should profane things sacred & holy," he told Emily, "were I to give vent to my feelings of love and devotion to you and ardent attachment to my children to men who might as soon as my back was turned make them the subject of jest and ridicule." In self-defense then David had become the very thing he hated about Washington, a liar and a façade misrepresenting his heart in the close quarters of posturing men. His own participation in the sham, of course, only brought home the vapidity of political life and drew him stronger than ever to the honest talk and genuine society of the ersatz family he created in letters scribbled on the floor of Congress. "How I wish I could to night fold you in my arms," he wrote Emily, "and in your caresses forget the harassing cares of this feverish life." "You have been to me," he confessed, "a priceless jewel and the fact that I have you to share my joys and help me bear the ills to which all mortals are subject doubly heightens the first, my love, my friend, the truest, kindest, noblest and best whom I ever expect to find on earth."5

But if he found the company of his wife so enchanting, why did David spend so much time away from her? This, of course, was their marriage's nagging little question-it grieved Emily to ask it because asked and re-asked it rang out plaintive and defeated-and it grieved David to answer it because while he found the question ludicrous and annoying, he also found it infuriatingly unanswerable, even to himself. Repeatedly, David assured his wife "how unsubstantial and unsatisfying…are all the excitements and even triumphs of public life when weighed against that domestic happiness which a man's wife and children bestow." But David must have recognized that his own conduct was difficult to square with these assurances of the primacy of home. Indeed, lacking a single satisfactory explanation, he combined myriad unsatisfactory ones in different proportions, never finding a mix he could throw his weight behind. Only once in his letters did David suggest that his absences were part of his duty to country, party, or district. "We all owe some duties to our country," he told his wife, "and we cannot from a feeling of selfishness shrink from the performance of them." For the most part, though, David treated his political career as something beyond his control, as if he had never made the choice to leave home for politics, and never having made this decision he had no power to extricate himself from its consequences. His involvement in public life, he claimed, was an historical accident. Local members of the Edonton Whig party had approached him with the notion that he campaign for the district's House seat. He was reluctant to run, but when he did and lost in a Whig district, it was too galling to his pride not to try at the next election to avenge the loss. And "after a man has once gotten into public life," he told his wife, "it is not so easy to get out of it." He assured Emily that he would never become a career politician, a man addicted to the excitement and passions of politicking, but he was also not ready to come home and not able to explain why. "We cannot always choose our own pathway," he noted helplessly. "We are to some extent the creatures of circumstances." But if he could not come home, why did Emily never join him in Washington? Partly, of course, familial and managerial duties kept her at home, particularly during her pregnancies. But a full answer requires a deeper understanding of David's abhorrence of Washington.6

* * *

"The virtue which distinguished our revolutionary ancestors is gone," David wrote his wife. "Congress is filled not with patriots but with mere politicians eager in the race of power and popularity." It is a common refrain, uttered almost reflexively by every generation that has succeeded the Founding Fathers'. David Outlaw, though, brought a special verve to his condemnation of life in the nation's capital.

Studying Gibbons's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire during the term, David believed that military men were taking over the country and that the young American republic, like its Roman predecessor, had developed a disquieting bloodlust and a strong addiction to military glory. "The ultimate consequences," he felt, were "likely to be most disastrous."

Already the American army was "large enough to make itself powerfully felt in the Halls of legislation." "How long will it be before rival chieftains" are marauding across the continent, contending "for the glittering prize of empire with armed legions?" In the deep tradition of twitchy small-r republicans, Outlaw eyed the stuffed uniforms parading around Washington with the suspicion of a man who believes he has been unjustifiably out-manned. "From a major general down to a lieutenant," he noted, every military man in Washington "thinks the eyes of all the nation are upon him and that he is destined to some high political distinction." But Outlaw was also astute enough to see in the new American fixation with militarism the fear of impotence which lurks in the small mind of the bully. Certainly it was galling that a man could be "brought forward and sustained" as a candidate "alone and if not so principally because he was a military man." Certainly it was a shame that a statesman like Henry Clay, who had "rendered [his country] more important and substantial service than all the military men of the present day" had to concede the political field to "men inexperienced and probably utterly unqualified" for office. But more disquieting was what the trend said about America more generally. Increased militarism, Outlaw discerned, was less a sign of America's confidence than its insecurity. "Courage is looked upon as the highest virtue" in this country, Outlaw noted, "and from the eagerness with which the populace run after it one would think we were a nation of cowards."7

Outlaw saw this same small-minded martial spirit operating in the halls of Congress. Never mind that factionalism had become so strident that Outlaw described his mess as composed not of "six democrats and five Whigs" but of "five Cass men, one Barnburner, four Taylor men and one Whig, to wit, your humble servant." Never mind that many congressmen slept in the chamber, talked through the speeches, or ran "into the house to vote and [were] out again as soon as their name [was] called." Never mind even that they cheated on their wives, gambled away their ill-gotten fortunes, or were regularly fall-down drunk in the House. All of this paled in comparison to the undercurrent of petty violence that ran through all the operations of government. "The present house contains an unusual number of large men," Outlaw noted humorously-"perhaps their constituents supposed there might be a general melee in which physical power might be as necessary as intellectual attainments." But of course, several melees did break out during Outlaw's term, and one of his close associates claimed to know seventy or eighty representatives who had pistols at the ready, concealed on their persons or in their desks.

When Henry Foote of Mississippi drew a gun from beneath his cloak, cocked the hammer and strode to the center aisle of the Senate to confront Col. Benton, Outlaw, like most of his contemporaries, was chagrined but not particularly surprised. "Nothing short of murder," he told his wife, "will arouse public indignation…and prevent the halls of legislation from being disgraced by scenes of outrage and violence." And indeed this was Outlaw's central point-not only was the conduct of the representatives deplorable, but so were the appetites of the represented. In the crowds that thronged the legislature Outlaw discerned a kind of sadistic glee, as if they were actually hoping "to see the Union dissolved by a general battle in the House."

"We are I fear," Outlaw wrote his wife, "running with fearful speed the race of ruin of all previous

republics."8

Obviously, Outlaw's gloomy perspective needs to be taken in context. Crusty republicans were not exactly a rare breed in the period, nor were bespectacled curmudgeons bursting at the seams with lessons overlearned from Roman history. The excesses of political life were things Outlaw loved to despise, the decadence and the scandals of his fellow representatives providing the perfect foil for his stiff moral posturing. Like the preacher who is never so happy as when steeped in sin, David's perennial grouchiness can sometimes be seen for what it was-the smug satisfaction of a good man content with his place in a bad world. But David's outlook cannot be dismissed as the typical prickliness of the overstarched Whig. Though politically priggish in somewhat familiar ways, Outlaw's perspective on Washington's "fashionable life" is both astute and revealing, involving deeply his complex notions of men and women, North and South.9

While David Outlaw was in Washington, the city's society was at its zenith. Spare and decadent, frenetic and sleepy by turns, the little village of Washington was, to judge from its infrastructure, ludicrously underdeveloped. Its distances were "magnificent," its architectural marvels abutted hovels and swamp land. Pennsylvania Avenue cut a huge swath through the city, providing "a perfect romping ground for…winds" that pestered the carefully-coifed sightseer with a fiendish delight. Maintaining one's dignity, not to mention one's umbrella, wig, tophat, or skirt, required the same studied balance of humor and reserve as the custom of feigned indifference to the stench wafting in from the sewage canals and shad fisheries. It was, as Outlaw noted, a capital not rich enough to accommodate a European court, not sincere enough to be the seat of republican government, a sprawling splendor putting on airs in the middle of a marsh. But if the infrastructure was awkwardly immature, the social life was ripe if not more so. As Virginia Tunstall Clay, the notorious belle of the fifties noted, "the capital was [at this time] synonymous with an unceasing, an augmenting round of dinners and dances, receptions and balls." "A hundred hostesses," she claimed, "renowned for their beauty and wit and vivacity vied with each other in evolving novel social relaxations." (One of Mrs. Clay's novel relaxations, it should be noted, was a box that rejuvenated her festive spirit by delivering her an acute electric shock.) Clay admitted there was a "reckless gaiety" to this Washington social scene and conceded that many of her closest friends were run "mad with rivalry and vanity"-but she never so much apologized for these facts as celebrated them.10

David Outlaw, as might be imagined, was not so gentle as Mrs. Clay in his estimation of Washington's reckless vanity. "Everything has a fair outside," David said of the city, "but it is in the language of Holy Writ a whited sepulcher.…It is all form, there is nothing real, nothing true about it.…We know not whom we can trust [or] upon whom rely." Part of David's problem was merely that he was lonely, an island of propriety in a sea of sin. He had no close associates and considered most of his fellow representatives selfish and corrupt. In the House he believed he bore witness to a "broad farce" where "scheme after scheme [was] offered to squander the public lands" and "dirty intrigues and maneuvers" attended "the miserable scramble for place." And in the wider Washington society Outlaw was, if possible, less comfortable. "The more I see of high-life or rather fashionable life," he wrote his wife, "the more am I disgusted with its hollow hypocrisy, its heartlessness and its deceit, and its utter selfishness." The "pander and pomp and ceremony" of the scenes Mrs. Clay so lovingly described were to Outlaw extravagant and petty, a "shabby gentility" that knew much of "mere decorums" but nothing of "real honor and nobleness of nature, chastity not merely of the person but of the mind and heart." Of course it was only more galling that Outlaw had to participate in the sham. Knowing that the city's dignitaries were meeting at the capitol, David sent a "servant in a carriage, closely shut up" to leave his card "with all the foreign ministers and the members of the cabinet." "What miserable flummery and farce," he grumbled, "and yet [this method] is a great convenience to make visits to persons whom you never saw and never care to see.…[My] visits will of course be returned in the same way."11

Then, too, the social pretenses of life at court offended Outlaw's political as well as personal proprieties, undermining his faith in America's republican experiment. He deemed the local papers, for instance, "aristocratic monsters" for their indulgent descriptions of the latest gala affairs. This "abominable fashion of putting in print the dresses &c of the ladies," he noted, "of giving their names or initials so that every body understands who is meant is copied from the Court Journals of foreign monarchies." Outlaw's arch journalistic nemesis was a Mrs. Royal, publisher of a particularly savage gossip sheet. Her strategy, David said, was to search "out the members of Congress and levy" what amounted to "black mail." He prided himself in the fact that she had not yet caught up with him, but granted that most representatives "take her paper to get rid of her for if they do not she abuses them…and no falsehood is too atrocious for her to publish." Even the papers that eschewed the merely salacious had a tendency to engage in a kind of cult of personality quite at odds with Outlaw's notion of a model republic. "It has become fashionable of late," he wrote home, "to publish every thing in the public prints. After a while I suppose whatever distinguished persons have for dinner, what time they go to bed, when they get up" will be the subject of late-breaking news. The gossip sheets, of course, were not Washington's only court affectation-Europe also set the tone for the capital's fashions, manners, and amusements. As Virginia Clay observed "foreign representatives and their suites formed a very important element" in Washington society. They were "our critics, if not our mentors," she noted, "and to be a favorite at the foreign legations was equivalent to a certificate of accomplishment and social charms." Outlaw, though, had little tolerance for such affectations. "Waltzing is you know fashionable here," he wrote Emily, "as I fully believe it would be to go naked if that were fashionable at foreign Courts.…[These] miserably abortive attempts to imitate the style and fashions of monarchical governments are to me perfectly disgusting."12

But it was not the aristocratic pretenses or sham civilities of the place that most often brought Outlaw's blood to a boil. At the heart of his blistering critique was sex. He admitted that he was prudish and somewhat behind the times in this "age of progress," but he also felt sure the age was progressing from "modesty and chastity" to "libertinism and licentiousness." Washington, he claimed, had become a "hollow hearted Sodom" in which "profligate men" and "abandoned women" gave themselves up to their animal urges. In his letters home he relayed several of the more lurid affairs in some detail. A Mrs. Jones, for instance, scandalized the city when she betrayed her breeding and a husband "devotedly attached to her" in a series of misadventures that ended with her fleeing to Baltimore and "taking laudanum very freely." Another scandal involved an unnamed senator who managed after one of his evening trysts to leave his love letters in a Washington hack. The affair was public information by breakfast. Still this indiscretion ended better than a love triangle broken only when the irate husband gunned down the offending paramour. And these examples, David promised his wife, were just some of the "many cases which occur here every session." "If all men who have cause to be jealous were to shoot a man in this city," he told her, "there would be a very considerable mortality here." Nor were the city socialites content to seek their sexual thrills behind closed doors. The city's museums, exhibition halls, and playhouses were often the purveyors of an astounding mélange of smut. Outlaw was particularly offended by an exhibition of model artists representing the world's most celebrated statues and paintings, some of them nudes. One of the exhibits, David noted, "represented an old man, gazing with intense interest upon a naked woman, and gazing at that part of her person which women most carefully conceal." The woman was "not actually in a state of nature," he noted, but was obscured only by "a slight drapery almost as thin as gauze…thrown a round [her] waist." Such exhibitions, he said, only contributed to the "looseness of morals" that would make Washington as "dissolute as any European Court."13

But while Outlaw railed against "profligate men," it was the "abandoned women" who inspired his most passionate sermons. He claimed to have a "great reverence…for virtuous women and [a] high appreciation of the influence which they exert on society." He believed that "female chastity and honor" constituted nothing less than the bedrock of all "public and private virtue" and felt that without a female influence "men would soon become savages." In Washington, however, the vast majority of women fell woefully below his standard. Old married ladies pranced about the capital, gallanted by "young coxcombs who have about as little brains in their heads as in their heels." They wasted all their time in making up their bodies and faces and tables and parlors and yet tended only to look ridiculous for all the effort. Outlaw admitted he had little knowledge of fashion but claimed he could spot "any thing outré in a lady's dress" and confessed to being "almost nervously sensitive to any thing like slovenliness." Mrs. Catron, for instance, seemed to be an intelligent woman but "dressed her head in a most ridiculous manner [with] curls enough to stuff a sofa." And an astounding number of ladies wore dresses so décolleté "[you] would not have had to make great changes to fit them for an exhibition of model artists." That these women treated Washington like a "fashionable place of resort for lounging and flirtations" was bad enough-that they involved themselves in politics was worse. "The practice is becoming very common here," he told his wife, "for ladies in person to solicit offices and favours of different kinds both from the Executive Departments and from the members of Congress." At this very "session of Congress," he told her, "a bill passed the House solely by the solicitations of a pretty woman. If it had been the case of a man it would not have received fifty votes." Such women were rarely content to peddle their influence in the lobbies. In some cases, he claimed, a congressman would be sent for, introduced into "a girl's bed room, she dressed in dishabille, and told if he would vote" a certain way "she could deny him nothing." One evening Outlaw himself was approached by a woman who "insisted upon my going up to her room." "Really," he told his wife, "I did not know but I should be ravished…and I positively declined to go."14

No doubt much of what Outlaw wrote was true-sex and politics, after all, have always made strange but inevitable bedfellows. Outlaw's extended commentary on the subject of women's sexuality, however, bordered on fixation, and one cannot but suspect that his Washington was oversexed in the same degree as he was repressed. For Outlaw, women's range of legitimate sexual expression was incredibly narrow. He despised alike women who appeared to have no sex and those who had any. One old woman disturbed him particularly because she did "not look like a woman." "I wish a person," he wrote crossly, "to be of one sex or another. One of these men-women or women-men are [equally] disgusting and disagreeable to me." But while he despised the he-women as having "the good traits of neither sex and what is revolting in both," he was more consistently disturbed by women who gave public space to the sexuality they did possess. Everywhere Outlaw looked he was presented with some unseemly press of bodies in which women indulged themselves in the rub of the crowd. He appears, in fact, to have been incapable of thinking about crowds without also thinking of women, and then in a sexual way, as if they were actually pressing in upon him. "There is nothing of interest in our house," he wrote his wife, "and yet the galleries are crowded with ladies." Without "regard to decency or propriety," he claimed, they literally squeezed themselves into the mob of onlookers. "I imagine they cannot be squeezed enough at home or they would not have a fancy to be brought into such close contact with entire strangers." Outlaw also described a public appearance of Henry Clay where women nearly "kissed the old fellow to death" and the statesman had "to make his retreat…to get clear of suffocation." "Now I do not believe in such things," Outlaw wrote home, "kisses are tokens of affection which a woman ought to reserve for her husband, father, brother, or very near relations." He admitted he was prudish on the subject but refused to alter his opinion. "I regard the preservation of [female] purity," he said, "as so important to [women's] own just influence [on] society that I view with abhorrence, with an abhorrence which I can not express, every thing calculated to break down even the outposts of their modesty." Waltzes and polkas topped the list of David's offenders. "If I were a single man," he claimed, "and engaged to a woman, to see her waltz with another gentleman would be sufficient to break it off." Many people, he admitted, say there is nothing wrong with the dance. And "so there is not abstractly, nor is there any thing wrong in feeling a woman's bosom, or kissing her, provided there is no improper feeling. But do not these liberties tend to produce improper passions? Do they not tend to other and still greater liberties?" Later in the year Outlaw read in the paper of a new dance "introduced at Saratoga…far surpassing in indecency and lasciviousness the polka or the waltz." The concluding step involved the gentleman throwing his leg over the lady's shoulder. "Whether the lady follows the modest and delicate example," he noted, "we are not informed, [but] every woman who has a proper regard for the dignity and respectability of her sex ought to set her face resolutely against these things."15

With each of these frothy condemnations of female sexual excess, with each lovingly-rendered and utterly gratuitous detail, Outlaw made it abundantly clear that he was not merely offended-he was titillated, tempted. At a crowded Washington exhibition, he found himself standing near a woman in a low-cut dress. At six-three Outlaw could peer right down the front of her gown and "see her bosom, nipples and all just as plainly as though she had never been dressed in her life." He of course decried the fashion as offensive to his "notions of propriety [and] good taste"-but he also looked, and probably more than once. When a newly-married couple moved into a room adjoining his, he was, he claimed, "obliged to hear a great deal that passes between them." "I can hear their kisses," he told his wife, "and other marks of endearment." But was he obliged to listen? Or did he strain to do so? Himself unsure of the answer he admitted the situation was "rather tantalizing, is it not?" And despite numerous diatribes against the evils of dance, Outlaw made it all but clear on one occasion that the great cruelty of the waltz was that he wasn't getting his turn on the floor. "I have a strong notion to go to a dancing school myself," he noted, "there is so much good hugging that I see no particular reason why I should not come in for my share. I dare say it would be quite pleasant to have a pretty girl in my arms, whirling around, with her eye voluptuously and languishingly looking into mine." While the great bulk of Outlaw's commentaries are categorical in their denunciation of open-tempered sexuality, there are these few occasions when his disapproval can be seen for what it was-the sour grapes of the disgruntled non-participant.16

But David did not blame himself for being tempted; indeed, as the crisis of union deepened in the 1850s he began to blame the North. Outlaw, it should be noted, was a unionist

Whig. As a congressman he consistently voted for sectional compromise, even opposing the conquest of Mexican territory for fear it would destroy the country. But he was not blind to sectional differences. Washington, after all, was the front line between the North and South, and he was thrown into a society very different from the inhabitants of his home town of Windsor, North Carolina. "There is an indescribable charm about home," he told Emily, "which no other place has, even though it be in a small village & mosquitoes do abound there. It has a holiness which appeals" to me, he said, because its people have "hearts which are not corrupted and hardened." Clearly, David believed that the people of Washington had been corrupted and hardened, partly from the excesses of capital life but also partly from their contact with the North. "Great crowds [of Southerners]," he told his wife, seem always "to be on their way North to spend their money."

"That [Yankees] should be more prosperous than we are is not at all surprising. There is scarcely an article of necessity or luxury in the way of manufactured goods we do not buy from them. The very brooms with which we sweep our floors, the utensils in which we cook, the clothes we wear, the chairs we sit on, the carpets upon which we tread, the bedding on which we sleep, all come from [them]." But these Southern tourists came home with more than consumer goods and empty pockets. They "bring back Northern manners." As might be imagined, Outlaw was particularly concerned about the effects of such junkets on Southern women. "There is a boldness, [a] brazenfacedness about Northern city women," he claimed, "as well as a looseness of morals which I hope may never be introduced south." "Many of our women who go there," he noted, "when they come home are dissatisfied. There is not excitement enough, their ordinary routine of domestic employments are distasteful. They long for the ball-room, the theatre, the gay crowd." So far as Outlaw acknowledged, there were no sleepy Windsors in the North, no places where the people were genuine and the mosquitoes constituted the greatest moral challenge. The North was for him synonymous with the city, with the crowd and the press of bodies. There, he claimed, "crime and corruption of all kinds grow rank and luxuriant."17

* * *

"It has often struck me as strange that any of us should wish to continue in public life," David Outlaw wrote his wife typically, "when we know from actual experience how unsatisfactory and unsubstantial are the objects we pursue with so much zeal and avidity, how utterly worthless they are compared with domestic enjoyment, with the love of a wife and children." David was sure he was not alone in the feeling. Beneath the pomp and the cheap thrills, he sensed in Washington an undercurrent of sadness, not of frustrated office-seekers or spent sybarites, but of husbands and fathers who missed their homes. "I have no doubt all public men have felt this at times," he told his wife, "and deeply regretted they should have ever entered upon the stormy career of politics." David, of course, had entered that career and seemed unable to leave it. But considering that he was so lonely and ill-suited to "fashionable life," why did he never invite Emily to join him in Washington? An argument might be made that Outlaw was concerned the city's corrupting influence would assail his wife's treasured modesty-but it is clear he trusted her implicitly in this regard. "It has often struck me," he wrote home, "how fortunate I was in my selection of a wife.… My own temper is naturally high and irascible. I am keenly sensible to [indecency and] I could not bear that my wife's honor should be breathed on by the breath of suspicion. Conceive then what I should have felt if I had been yoked to a woman who was flirting with every body." Emily, though, was of a different breed, a "noble-hearted, kind and affectionate woman" who devoted "all her thoughts and endeavours to smooth [her husband's] rugged path." I have "implicit confidence in your virtue and prudence, David told her, and "unbounded confidence in [your] chastity." But it was precisely this confidence, this purity that made it impossible for him to feel comfortable bringing Emily to the capital. He had learned and relearned in his nightly reading the greatest lesson history has to teach-the things most worth preserving are invariably the most delicate. Everything Outlaw truly cared about, everything he believed in-his wife, his family, Windsor, the republic-were, concomitant to their very goodness, threatened by the corrupting influences ever pressing in upon the worthy. For reasons he did not exactly understand he had ventured out into that press, into a world bent on running its "race of ruin." He railed against those excesses, but it did not escape his attention that his heart was not so pure, nor his character so innocent, as they had been in youth. Emily, then, was the part of him incorruptible, unassailable; she was the home town, the South, the republic he would return to when he shook free of the "ambitious men [and] scheming women" slumming around his "hollow hearted Sodom." Until then David Outlaw would keep his head down in the House, scribble his daily letters home, dream of the simple joys of a "stroll through a [Windsor] corn field," and dwell on "pleasures of memory…almost equal to those of hope."18

-------------------------

Notes

1. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 29, 1849, David Outlaw Papers, SHC (hereafter, unless otherwise noted, all references are to this collection); David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, July 28, 1848. On the general tenor of the House during the debates that would culminate in the Compromise of 1850, see: Holman Hamilton, Prologue to Conflict: The Crisis and Compromise of 1850 (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1964); Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850s (New York: Wiley, 1978); Edwin Charles Rozwenc, The Compromise of 1850 (Boston: D. C. Heath, 1957); and Merrill D. Peterson, The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, and Calhoun (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987). Outlaw's assessment that "negroes" constituted the "everlasting topic" of debate before the assembly echoes that of Thomas Hart Benton, senator from Missouri, who likened the omnipresence of the slavery issue in 1848 to a biblical plague: "You could not look upon the table but there were frogs. You could not sit down at the banquet table but there were frogs. You could not go to the bridal couch and lift the sheets but there were frogs. We can see nothing, touch nothing, have no measures proposed, without having this pestilence thrust before us."

2. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 3, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, August 5, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 20, 1848; Emily Outlaw to David Outlaw, January, 19, 1850. Outlaw's particularities on the subject of vanity and pride put one in mind of Jane Austen's musings on the same: "Vanity and pride are different things, though the words are often used

synonymously. A person may be proud without being vain. Pride relates more to our opinions of ourselves, vanity to what we would have others think of us." (Pride and Prejudice, Penguin Classics, 20). If Outlaw read Austen, he does not mention it.

3. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, June 6, 1850; Emily Outlaw to David Outlaw, May 28, 1852; Emily Outlaw to David Outlaw, January 29, 1850.

4. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 4, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, July 24, 1850.

5. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 16, 1847; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 12, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, July 27, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, March 12, 1848.

6. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 8, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, May 23, 1850.

7. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 7, 1847; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, August 10, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, undated January 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 7, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 14, 1847; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 16, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 14, 1847.

8. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, March 13, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, August 1, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 15, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 4, 1849; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, May 5, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, undated January 1848.

9. A delightful study of crusty (small-r) republicanism is Harry L. Watson, "Squire Oldway and His Friends: Opposition to Internal Improvements in Antebellum North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review (1977), 105-119.

10. Mrs. Clay's famous study of Washington in the period, it should be remembered, was written after the fact, with that peculiar romantic hindsight Southerners brought to the examination of all things antedating the Unpleasantness. In her memory, at least, Washington was a resplendent court at "the very apex of its social glory." Fewer states meant fewer representatives, making society "correspondingly select." Moreover, she noted, "many distinguished men…retained their positions in the political foreground for…many years," and when they finally died or retired their sons often succeeded them, "inheriting, in some degree, their ancestors friends" and creating "a social security" that lent "charm and prestige to the fashionable coteries of the Federal centre." Troubled by the irksome instabilities of the democratic process, Mrs. Clay chose in retrospect to emphasize the degree to which the political cream rose to the top and stayed there. True courtiers, after all, cannot be swanking about the backcountry prostrating themselves for votes when they need to be composing bad poetry for the court belles. Virginia Tunstall Clay, A Belle of the Fifties; Memoirs of Mrs. Clay, of Alabama, Covering Social and Political Life in Washington and the South, 1853-66 (New York: Doubleday, 1905), 28, 29, 86, 87. For other contemporary perspectives on Washington society, see: T. C. DeLeon, Four Years in Rebel Capitals: An Inside View of Life in the Southern Confederacy, From Birth to Death; From Original Notes, Collated in the Years 1861 to 1865 (Mobile: The Gossip Printing Company, 1892); Francis J. Grund, ed., Aristocracy in America. From the Sketchbook of a German Nobleman (London: R. Bentley, 1839); John von Sonntag de Havilland, A Metrical Description of a Fancy Ball Given at Washington, 9th April, 1858 (Washington: F. Philip, 1858); Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House, with an introduction by James Olney (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); Elizabeth Lomax, Leaves From an Old Washington Diary, 1854-1863 (Mount Vernon: Golden Eagle Press, 1941); Benjamin Perley Poore, Perley's Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis, (New York: W. A. Houghton, 1886); Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, Portrayed by the Family Letters of Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith (New York, Scribner, 1906); and Anne Hollingsworth Wharton, SocialLife in the Early Republic (Williamstown: Corner House, 1970).

11. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 21, 1847; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, July 3, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 12, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 7, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 6, 1847; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 27, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 14, 1850.

12. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 21, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 7, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 7, 1849; Virginia Tunstall Clay, A Belle of the Fifties, 37; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, March 26, 1848.

13. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, March 12, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 5, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 27, 1849; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 15, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 27, 1849.

14. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, August 7, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 16, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 18, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 18, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 16, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 10, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 18, 1851; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 11, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 11, 1851; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 16, 1847; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 25, 1850.

15. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 6, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 11, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 3, 1849; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, February 11, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, March 12, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 30, 1849; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, August 7, 1850.

16. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, January 18, 1851; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, August 10, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, March 26, 1848.

17. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, June 16, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, June 26, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, June 16, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, July 27, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 4, 1849.

18. David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, June 16, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, December 8, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, June 16, 1850; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, March 17, 1848; David Outlaw to Emily Outlaw, June 25, 1850. Given Outlaw's sense that he was himself defiled by his association with Washington, much might be made of the fact that he appears to have been a chronic bather. Even in the dead of winter he tended to bathe in cold water and in the summers he took a "shower bath every morning" and washed himself "from head to foot with cold water" every afternoon. I have resisted interpreting these habits for want of evidence but merely mention Outlaw's belief that "it is a real luxury to feel that you are clean." Certainly Outlaw was not the only one to feel the stink of the city upon him. As a friend wrote William Porcher Miles in 1858: "Don't let Washington spoil you. I am afraid that continual intercourse with those abolitionists will hurt any decent man and that the Halls of congress are like a dirty privy, a man will carry off some of the stink even in his clothes." (Benjamin Evans to William Porcher Miles, March 4, 1858, William Porcher Miles Papers, SHC).

Southern Unionist - In the United States, Southern Unionists were people living in the Confederate States of America, opposed to secession, and against the Civil War. These people are also referred to as Southern Loyalists, Union Loyalists, and Lincoln Loyalists. During Reconstruction these terms were replaced by Scalawag, which covered all Southern whites who supported the Republican party.

Whig Party (United States) - The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s[1], the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party.

In particular, the Whigs supported the supremacy of Congress over the presidency, and favored a program of modernization and economic protectionism. This name was chosen to echo the American Whigs of 1776, who fought for independence, and because "Whig" was then a widely recognized label of choice for people who saw themselves as opposing autocratic rule.[2] The Whig Party counted among its members such national political luminaries as Daniel Webster, William Henry Harrison, and their preeminent leader, Henry Clay of Kentucky. In addition to Harrison, the Whig Party also counted four war heroes among its ranks, including Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. Abraham Lincoln was the chief Whig leader in frontier Illinois.

In its two decades of existence, the Whig Party saw two of its candidates, William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, elected president. Both, however, died in office. John Tyler became president after Harrison's death, but was expelled from the party. Millard Fillmore, who became president after Taylor's death, was the last Whig to hold the nation's highest office.

The party was ultimately destroyed by the question of whether to allow the expansion of slavery to the territories. With deep fissures in the party on this question, the anti-slavery faction successfully prevented the renomination of own incumbent President Fillmore in the 1852 presidential election; instead, the party nominated General Winfield Scott. Most Whig party leaders thereupon quit politics (as Lincoln did temporarily) or changed parties. The voter base defected to the Republican Party, various coalition parties in some states, and to the Democratic Party. By the 1856 presidential election, the party had lost its ability to maintain a national coalition of effective state parties and endorsed Millard Fillmore, of the American Party by that time, at its last national convention.[3]

Indian Woods in Windsor, North Carolina

Indian Woods

US 13, Windsor, NC, USA

Latitude & Longitude: 36° 0' 6.9192", -76° 57' 45.018"

North Carolina State

Historical Marker

"Reservation established in 1717 for Tuscaroras remaining in N.C. after war of 1711-1713. Sold, 1828. Five miles N.W."

Tuscarora Indians in eastern North Carolina were divided into two factions in the early eighteenth century.

The Northern Tuscarora or Upper Towns were led by Chief Tom Blunt and the Southern or Lower Towns by Chief

Hancock. When European settlers began entering the Tuscarora territory, they brought disease and often engaged in trade which was unfair to the native people, some of whom they enslaved.

Chief Hancock grew tired of being exploited. In early September 1711 the Tuscarora captured the organizers of the settlement at New Bern, Christopher von Graffenried, John Lawson, and two of their slaves. Lawson was tortured and murdered. Graffenreid was released because the Tuscarora believed that he was the governor of the colony.

Later that month Chief Hancock led his people into white settlements along the Trent and Pamlico rivers and massacred white men, women, and children, launching the Tuscarora War. The colonial government of North Carolina was aided by Virginia and South Carolina. Indians in surrounding areas who had been enemies of Hancock and his tribe came to his side.

The decisive battle came in March 1713 at the Tuscarora stronghold of Nooherooka in what is now Greene County. The war ended in 1717.

Chief Tom Blunt and the Northern Tuscarora tribe were rewarded for helping the white settlers during the war and for capturing Chief Hancock. The colonial government gave Chief Blunt a tract of 53,000 acres, on the north side of the Roanoke River in what is now southwestern Bertie County. The area came to be known as Indian Woods. Indians declining to settle on the tract left North Carolina and settled in Niagara County, New York. They eventually joined the Five Nations of Indians in the area.

In 1828, the Tuscarora still remaining in North Carolina gave up their title and rights to Indian Woods. Around 645 Tuscarora families remained and moved to other parts of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina.

...

The Southern Tuscarora, led by Chief Hancock, worked in conjunction with the Pamplico Indians, the Cothechneys, the Cores, the Mattamuskeets and the Matchepungoes to attack the settlers in a wide range of locations in a short time period. Principle targets were the planters on the Roanoke River, the planters on the Neuse and Trent Rivers and the city of Bath. The first attacks began on September 22nd, 1711, and hundreds of settlers were ultimately killed. Several key political figures were either killed or driven off in the subsequent months.

Governor Edward Hyde called out the militia of North Carolina, and secured the assistance of the Legislature of South Carolina, who provided "six hundred militia and three hundred and sixty Indians under Col. Barnwell". This force attacked the Southern Tuscarora and other tribes in Craven County at Fort Narhantes on the banks of the Neuse River in 1712. The Tuscarora were "defeated with great slaughter; more than three hundred savages were killed, and one hundred made prisoners." These prisoners were largely women and children, who were ultimately sold into slavery.

Chief Blunt was then offered the chance to control the entire Tuscarora tribe if he assisted the settlers in putting down Chief Hancock. Chief Blunt was able to capture Chief Hancock, and the settlers executed him in 1712. In 1713 the Southern Tuscaroras lost Fort Neoheroka, with 900 killed or captured.

It was at this point that the majority of the Southern Tuscarora began migrating to New York to escape the settlers in North Carolina.

The remaining Tuscarora signed a treaty with the settlers in June 1718 granting them a tract of land on the Roanoke River in what is now Bertie County. This was the area already occupied by Tom Blunt, and was specified as 56,000 acres (227 km²); Tom Blunt, who had taken on the name Blount, was now recognized by the Legislature of North Carolina as King Tom Blount. The remaining Southern Tuscarora were removed from their homes on the Pamlico River and made to move to Bertie. In 1722 Bertie County was chartered, and over the next several decades the remaining Tuscorara lands were continually diminished as they were sold off in deals that were frequently designed to take advantage of the Native Americans.

Colonial and state political history of Hertford County, N. C. by Winborne, Benjamin B.

...

HERTFORD

COUNTY.

On the 12th day of December, 1758, John Campbell, a member from Bertie in the

Colonial General Assembly of North Carolina, presented, a petition asking for,

the erection of Hertford County from the territory of Chowan, Bertie, and

Northampton. On the 18th day of December, 1759, Benj. Wynns, one of the

members from Bertie, was ordered to prepare and bring in a bill pusuant to, the

prayer, of the petition, which he did, and the same was presented and passed and

sent to the Council. On December 19, 1759, it was endorsed and sent to the upper

house, where it was first

read and passed. The bill was finally passed December 29, 1759, and the county

given two members in, the General Assembly. The boundary being as follows:

Beginning in Bertie County at the first high land on the northwest side of Mare

Branch on Chowan River Pocosin, running thence by a direct line to Thos.

Outlaw's plantation, near Stony Creek, thence by a direct line to

Northampton County line at the plantation whereon James Rutland formerly lived,

then along Northampton County line to the head of Beaver Dam Swamp, then by a

line direct to the easternmost part of Kirby Creek, thence down the creek to the

Meherrin River; then up the Meherrin River to the Virginia line; then easterly

along the Virginia line to Bennett's Creek; then down Bennett's Creek to Chowan

River; then across the river to the mouth of the said Mare Branch; and up the

branch to the beginning, and all of said territory shall be known as Hertford

County, and parish of St. Barnabas.

...

Governor Josiah Martin and the Assembly. The Superior Court for each county

still exists in North Carolina, presided over by a district judge, and the

criminal docket prosecuted on behalf of the State by a district solicitor,

except that the attorney-general of the State was required to perform the duties

of solicitor in the third district, in which Wake County was located, up to

1868. After that date a solicitor was required to be elected in each district.

W. N. H. Smith, of Hertford County, succeeded David Outlaw, of Bertie County,

as Solicitor of the district in 1847, and Smith was succeeded in 1857 by

Elias C. Hines of Chowan. Hines was succeeded in 1863 by Jesse J. Yeates, of

Hertford, and Yeates was succeeded in 1867 by Mills L. Eure, of Gates. The

judges and solicitors, prior to 1868, were elected by the General Assembly;

since that date they have been elected by the people. The Superior Court judges

have always been required in North Carolina to rotate and hold the courts of a

different district each spring and fall, except the period between July, 1868,

and 1876. Since 1868, Hertford County has not been allowed to remain in any

judicial district long enough for any of her sons to aspire to judicial honors

in the district.

...

The first column contains the heads of families, the second the number of

free white males over 16 years, including the heads of families, the third the

number of free white males under 16 years, the fourth the number of free white

female, including heads of families, the fifth the number of free negroes, and

the sixth the number of slaves owned by the several families:

| Outlaw, Wm. | 3 | 4 | 3 | .. | 19 |

| Outlaw, Thomas | 1 | 3 | 5 | .. | 4 |

| Outlaw, Lewis | 1 | 1 | 2 | .. | 1 |

| Overton, James | 1 | 1 | 2 | .. | .. |

...

Senator Sharp was the eldest son of Maj. Jacob Sharp and the grandson of Starkey Sharp and his wife, Sarah Winborne. His mother was a Nancy Hunter, of Gates County. He married Sallie Carter, daughter of Major Isaac Carter, and reared two sons and a daughter. His son, Jacob H. Sharp, was a brave Confederate soldier from Mississippi, and was promoted before the end of the conflict to the rank of Brigadier General, and is now living in Columbus, Mississippi. His second son, Thos. L. Sharp, was also a gallant Confederate soldier from his native county. He entered the army as Captain, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and was killed in battle at Atlanta, Ga., in 1864. E. H. Sharp had several brothers and one sister.

In 1827 Mr. Sharp was defeated for the Senate by David O. Askew, of Pitch Landing, who was the grandson of Thomas Outlaw, of Stony Creek, in Bertie County, whose farm is mentioned in the boundary of Hertford County, and a nephew of the old legislator and Moderator of the Chowan Baptist Association, George Outlaw, of Bertie.

Mr. Askew was in the Senate again in 1828. Shortly after his return from the Senate he emigrated to Mississippi, where he still has a number, of descendants.

His brother, Dr. George O. Askew, was in the Senate from Bertie in 1827, and

remained a member of that body for six years. The eminent physician, Dr. A. J.

Askew, of Bertie, who married Miss Ward, of Norfolk, Va., was also a brother of

the Senator. David O. Askew married Martha Etheridge. Their cousin, John O.

Askew, of Pitch Landing, was the son of George Askew and wife Annie, the

daughter of George Outlaw, the old Moderator, and he was the cousin to the old

Congressman, David Outlaw.

The Askews and Outlaws were people of wealth and prominence in the eastern

part of the State.

...

In 1853 the Whigs renominated and elected Col. David Outlaw, of Bertie, to

Congress. Colonel Outlaw was a lawyer of consummate ability and a regular

attendant upon the courts of Hertford, where he had many kin and a large

clientage.