Ukraine Journalism -

http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/2012/11/21/how-stalin-s-terrible-famine-in-ukraine-was-exposed-by-a-western-mail-writer-91466-32278424/How Stalin’s terrible famine in Ukraine was exposed by a Western Mail writer WalesOnline

Nov 21 2012

This

weekend sees the anniversary of the famine Stalin engineered to kill

millions in Ukraine. Here Mick Antoniw AM, the son of Ukrainian emigres,

gives a personal account of Holodomor, as it is known

This

weekend in Ukraine and in Ukrainian communities and homes across the

world people will be commemorating the 79th anniversary of the

“Holodomor”, the artificial famine created by Stalin which led to the

deaths over an 18 month period during 1932-33 of more than seven million

Ukrainian men, women and children. The precise figures will never be

known but estimates range between six and ten million dead.

...

...

British

and indeed international investigative journalism failed spectacularly.

On the other side, the best of British journalism was exemplified by

journalists such as Malcolm Muggeridge and in particular the Western

Mail journalist, Gareth Jones.

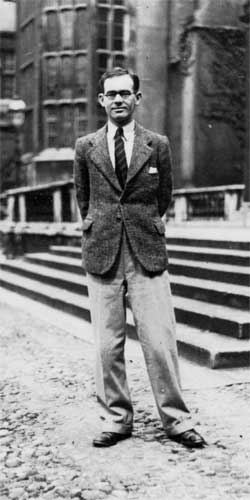

After graduating from

Cambridge in 1929, Barry-born Gareth made his first visit to Hughesovka

(Donetsk) where he saw the first signs of famine. In 1933 he visited

Soviet Ukraine again and defied a ban on travelling to visit the famine

affected regions.

During his March 1933 “off limits”

walking tour of Ukraine he witnessed the famine first hand and reported:

“I walked alone through villages and twelve collective farms.

Everywhere was the cry: ‘There is no bread, we are dying’.

“In

one of the peasant’s cottages in which I stayed we slept nine in the

room. It was pitiful to see that two out of the three children had

swollen stomachs. All there was to eat in the hut was a very dirty

watery soup, with a slice or two of potato.

“Fear of death

loomed over the cottage, for they had not enough potatoes to last until

the next crop. When I shared my white bread and butter and cheese one of

the peasant women said: ‘Now I have eaten such wonderful things I can

die happy’. I set forth again further towards the south and heard the

villagers say: ‘We are waiting for death’.

“During the famine around 20-25% of the population of Soviet Ukraine was exterminated including a third of Ukraine’s children. “That

the famine was a direct product of Stalin’s political leadership was

illustrated by the gruesome statement of leading communist MM

Khatayevich who summed up the official position thus: ‘A ruthless

struggle is going on between the peasantry and our regime. It’s a

struggle to the death. This year was a test of our strength and their

endurance. It took a famine to show them who is master here. It has cost

millions of lives, but the collective farm system is here to stay.

We’ve won the war’.”

Gareth Jones was vilified and

ostracised for reporting honestly what he saw. He was nevertheless one

of the few who stood up and maintained the highest journalistic

principles. He was banned by the Soviet authorities from re- entering

the Soviet Union. Two years later he was murdered in suspicious

circumstances in Manchuria in 1935. In recognition

of Gareth Jones’ exposure of the famine a memorial plaque in English,

Welsh and Ukrainian was unveiled in Aberystwyth in May 2006.

In November 2008 I attended a ceremony in London at which his nephew was awarded the Ukrainian Order of Freedom.

Wales

has an unusual historic connection with Ukraine mainly arising out of

its common industrial heritage. In Gareth Jones, Wales can be proud of

something else; at a time when many turned a blind eye to the terrible

events in Ukraine, it was a Welshman who stood up and told the world the

truth.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1038774/Holocaust-hunger-The-truth-Stalins-Great-Famine.htmlHolocaust by hunger: The truth behind Stalin's Great FamineBy Simon Sebag Montefiore

UPDATED:19:50 EST, 25 July 2008

The

demented Roman Emperor Caligula once mused that if all the people of

Rome had one neck he would cut it just to be rid of his troublesome

people. The trouble was there were simply too many Romans to kill them

all. Many centuries later, the brutal Soviet dictator

Josef

Stalin reflected that he would have liked to deport the entire

Ukrainian nation, but 20 million were too many to move even for him.

...

So he found another solution: starvation. Now,

75 years after one of the great forgotten crimes of modern times,

Stalin's man-made famine of 1932/3, the former Soviet republic of

Ukraine is asking the world to classify it as a genocide.

The

Ukrainians call it the Holodomor - the Hunger. Millions starved as

Soviet troops and secret policemen raided their villages, stole the

harvest and all the food in villagers' homes.

They

dropped dead in the streets, lay dying and rotting in their houses, and

some women became so desperate for food that they ate their own

children. If they managed to fend off starvation, they were deported and shot in their hundreds of thousands.

So

terrible was the famine that Igor Yukhnovsky, director of the Institute

of National Memory, the Ukrainian institution researching the

Holodomor, believes as many as nine million may have died.

For

decades the disaster remained a state secret, denied by Stalin and his

Soviet government and concealed from the outside world with the help of

the 'useful idiots' - as Lenin called Soviet sympathisers in the West.

Russia

is furious that Ukraine has raised the issue of the famine: the

swaggering 21st-century state of Prime Minister Putin and President

Medvedev see this as nationalist chicanery designed to promote Ukraine,

which may soon join Nato and the EU.

They see it as an anti-Russian manoeuvre more to do with modern politics than history. And

they refuse to recognise this old crime as a genocide [ Ah but it is DEMOCIDE!] .

They

argue that because the famine not only killed Ukrainians but huge

numbers of Russians, Cossacks, Kazakhs and many others as well, it can't

be termed genocide - defined as the deliberate killing of large numbers

of a particular ethnic group.

It may be a strange defence, but it is historically correct.

So what is the truth about the Holodomor? And why is Ukraine provoking Russia's wrath by demanding public recognition now?

The

Ukraine was the bread basket of Russia, but the Great Famine of 1932/3

was not just aimed at the Ukrainians as a nation - it was a deliberate

policy aimed at the entire Soviet peasant population - Russian,

Ukrainian and Kazakh - especially better-off, small-time farmers.

It was a class war designed to 'break the back of the peasantry',

a war of the cities against the countryside and, unlike the Holocaust,

it was not designed to eradicate an ethnic people, but to shatter their

independent spirit.

So while it may not be a formal case of genocide, it does, indeed, rank as one of the most terrible crimes of the 20th century.

To

understand the origins of the famine, we have to go back to the October

1917 Revolution when the Bolsheviks, led by a ruthless clique of

Marxist revolutionaries including Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin, seized

power in the name of the workers and peasants of the Russian Empire to

create a Marxist paradise, using terror, murder and repression.

The

Russian Empire was made of many peoples, including the Russians,

Ukrainians, Kazakhs and Georgians, but the great majority of them,

especially in the vast arable lands of Ukraine, southern Russia, the

northern Caucasus, and Siberia, were

peasants, who dreamed only of owning their own land and farming it.

Initially, they were thrilled with the Revolution, which meant the

breakup of the large landed estates into small parcels which they could farm.

But the peasants had no interest in the Marxist utopian ideologies that obsessed Lenin and Stalin.

Once

they had seized their plots of land, they were no longer interested in

esoteric absurdities such as Marx's stages in the creation of a

classless society.

The fact is they were essentially

conservative and wanted to pass what little wealth they had to their children.

This

infuriated Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who believed that the peasantry,

especially the ones who owned some land and a few cows, were a huge

threat to a collectivist Soviet Russia.

Lenin's hatred of the peasantry

became clear when a famine occurred in Ukraine and southern Russia in

1921, the inevitable result of the chaos and upheaval of the Revolution.

With his bloodthirsty loathing for all enemies of the Revolution,

he said 'Let the peasants starve',

and wrote ranting notes ordering the better-off peasants to be hanged

in their thousands and their bodies displayed by the roadsides.

Yet

this was an emotional outburst and, ever the ruthless pragmatist, he

realised the country was so poor and weak in the immediate aftermath of

its revolutionary civil war that the peasants were vital to its

survival. So instead, he embraced what he called a New Economic Policy,

in effect a temporary retreat from Marxism, that allowed the peasants to

grow crops and sell them for profit. It was always planned by Lenin and

his fellow radicals that this New Economic Policy should be a stopgap

measure which would soon be abandoned in the Marxist cause.

But before this could happen, Lenin died in 1924 and Stalin defeated all his rivals for the Soviet leadership.

Then,

three years later, grain supplies dropped radically. It had been a poor

crop, made worse by the fact that many peasant farmers had shifted from

grain into more lucrative cotton production.

Stalin travelled across Russia to inspect supplies and ordered forcible seizures of grain from the peasantry.

Thousands

of young urban Communists were drafted into the countryside to help

seize grain as Stalin determined that the old policies had failed.

Backed by the young, tough Communists of his party, he devised what he called

the Great Turn:

he would seize the land, force the peasants into collective farms and

sell the excess grain abroad to force through a Five Year Plan of

furious industrialisation to make Soviet Russia a military super power.

He

expected the peasants to resist and decreed anyone who did so was a

kulak - a better-off peasant who could afford to withhold grain - and

who was now to be treated as a class enemy. By 1930, it was clear the

collectivisation campaign was in difficulties.

There was less

grain than before it had been introduced, the peasants were still

resisting and the Soviet Union seemed to be tottering.

Stalin, along with his henchman Vyacheslav Molotov and others, wrote a ruthless memorandum ordering

the 'destruction of the kulaks as a class'. They

divided huge numbers of peasants into three categories.

The

first was to be eliminated immediately; the second to be imprisoned in

camps; the third, consisting of 150,000 households - almost a million

innocent people - was to be deported to wildernesses in Siberia or Asia.

Stalin

himself did not really understand how to identify a kulak or how to

improve grain production, but this was beside the point.

What

mattered was that sufficient numbers of peasants would be killed or

deported for all resistance to his collectivisation programme to be

smashed.

In letters written by many Soviet leaders, including

Stalin and Molotov, which I have read in the archives, they repeatedly

used the expression:

'We must break the back of the peasantry.' And they meant it.

In

1930/1, millions of peasants were deported, mainly to Siberia. But

800,000 people rebelled in small uprisings, often murdering local

commissars who tried to take their grain.

So

Stalin's top henchmen led armed expeditions of secret policemen to crush 'the wreckers', shooting thousands.The

peasants replied by destroying their crops and slaughtering 26 million

cattle and 15 million horses to stop the Bolsheviks (and the cities they

came from) getting their food. Their mistake was to think they were dealing with ordinary politicians.

But the Bolsheviks were far more sinister than that:

if many millions of peasants wished to fight to the death, then the Bolsheviks were not afraid of killing them.

It

was war - and the struggle was most vicious not only in the Ukraine but

in the north Caucasus, the Volga, southern Russia and central Asia.

The

strain of the slaughter affected even the bull-nerved Stalin, who

sensed opposition to these brutal policies by the more moderate

Bolsheviks, including his wife Nadya. He knew Soviet power was suddenly

precarious, yet Stalin kept selling the grain abroad while a shortage

turned into a famine.

More than a million peasants were deported to Siberia: hundreds of thousands were arrested or shot.

Like

a village shopkeeper doing his accounts, Stalin totted up the numbers

of executed peasants and the tonnes of grains he had collected. By

December 1931, famine was sweeping the Ukraine and north Caucasus.

'The peasants ate dogs, horses, rotten potatoes, the bark of trees, anything they could find,' wrote one witness Fedor Bleov.

By

summer 1932, Fred Beal, an American radical and rare outside witness,

visited a village near Kharkov in Ukraine, where he found all the

inhabitants dead in their houses or on the streets, except one insane

woman.

Rats feasted on the bodies.

Beal found messages next to the bodies such as: 'My son, I couldn't wait. God be with you.'

One

young communist, Lev Kopolev, wrote at the time of 'women and children

with distended bellies turning blue, with vacant lifeless eyes. 'And

corpses. Corpses in ragged sheepskin coats and cheap felt boots; corpses

in peasant huts in the melting snow of Vologda [in Russia] and Kharkov

[in Ukraine].'

Cannibalism was rife and some women offered sexual favours in return for food.

There are horrific eye-witness accounts of mothers eating their own children.

In

the Ukrainian city of Poltava, Andriy Melezhyk recalled that neighbours

found a pot containing a boiled liver, heart and lungs in the home of

one mother who had died.

Under a barrel in the cellar they

discovered a small hole in which a child's head, feet and hands were

buried. It was the remains of the woman's little daughter, Vaska.

A boy named Miron Dolot described the countryside as 'like a battlefield after a war.

'Littering

the fields were bodies of starving farmers who'd been combing the

potato fields in the hope of finding a fragment of a potato.

'Some frozen corpses had been lying out there for months.'

On

June 6, 1932, Stalin and Molotov ordered 'no deviation regarding

amounts or deadlines of grain deliveries are to be permitted'.

A

week later, even the Ukrainian Bolshevik leaders were begging for food,

but Stalin turned on his own comrades, accusing them of being wreckers.

'The Ukraine has been given more than it should,' he stated.

When

a comrade at a Politburo meeting told the truth about the horrors,

Stalin, who knew what was happening perfectly well, retorted: 'Wouldn't

it be better for you to leave your post and become a writer so you can

concoct more fables!'

In the same week,

a train pulled into Kiev from the Ukrainian villages 'loaded with corpses of people who had starved to death', according to one report. Such tragic sights had no effect on the Soviet leadership.

When the American Beal complained to the Bolshevik Ukrainian boss, Petrovsky, he replied:

'We know millions are dying. That is unfortunate, but the glorious future of the Soviet Union will justify it.' Stalin was not alone in his crazed determination to push through his plan.

The archives reveal

one young communist admitting: 'I saw people dying from hunger, but I firmly believed the ends justified the means.'Though

Stalin was admittedly in a frenzy of nervous tension, it was at this

point in 1932 when under another leader the Soviet Union might have

simply fallen apart and history would have been different.

Embattled

on all sides, criticised by his own comrades, faced with chaos and

civil war and mass starvation in the countryside, he pushed on

ruthlessly - even when,

in 1932, his wife Nadya committed suicide, in part as a protest against the famine.

'It seems in some regions of Ukraine, Soviet power has ceased to exist,' he wrote.

'Check the problem and take measures.' That meant the destruction of any resistance.

Stalin

created a draconian law that any hungry peasant who stole even a husk

of grain was to be shot - the notorious Misappropriation of Socialist

Property law.

'If we don't make an effort, we might lose Ukraine,' Stalin said, almost in panic.

He dispatched ferocious punitive expeditions led by his henchmen, who engaged in mass murders and executions.

Not

just Ukraine was targeted - Molotov, for example, headed to the Urals,

the Lower Volga and Siberia. Lazar Kaganovich, a close associate of

Stalin, crushed the Kuban and Siberia regions where famine was also

rife.

Train tickets were restricted and internal passports

were introduced so that it became impossible for peasants to flee the

famine areas.

Stalin called the peasants 'saboteurs' and declared

it 'a fight to the death! These people deliberately tried to sabotage

the Soviet stage'.

Between four and five million died in Ukraine,

a million died in Kazakhstan and another million in the north Caucasus

and the Volga.

By 1933, 5.7 million households - somewhere between ten million and 15 million people - had vanished. They had been deported, shot or died of starvation.

As for Stalin, he emerged more ruthless, more paranoid, more isolated than before.

Stalin

later told Winston Churchill that this was the most difficult time of

his entire life, harder even than Hitler's invasion. 'It

was a terrible struggle' in which he had 'to destroy ten million. It

was fearful. Four years it lasted - but it was absolutely necessary'.

Only in the mind of a brutal dictator could the mass murder of his own people be considered 'necessary'.

Whether it was genocide or not, perhaps now the true nature of one of the worst crimes in history will finally be acknowledged.

• Sashenka, a novel of love, family, death and betrayal in 20th century Russia, by Simon Sebag Montefiore, is out now.

Author

Topic: Death by Gun Control - Democide (Read 16050 times)

Author

Topic: Death by Gun Control - Democide (Read 16050 times)