King Edwy - Saint Dunstan - King Edgar

This compares the "Outlawe" banishment story by

King Edwy and their return with that

of St. Dunstan banishment by Edwy and his return with King Edgar.

The Outlawe legend:

From "A

visitation of the seats and arms of the noblemen and gentleman of Great Britain

by Bernard Burke" it says :

From "A

visitation of the seats and arms of the noblemen and gentleman of Great Britain

by Bernard Burke" it says :

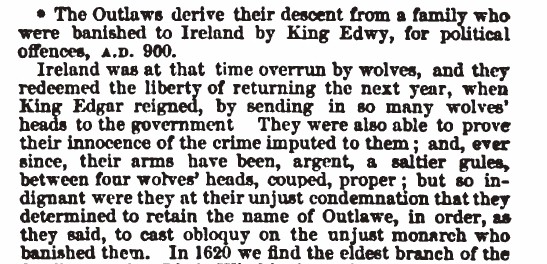

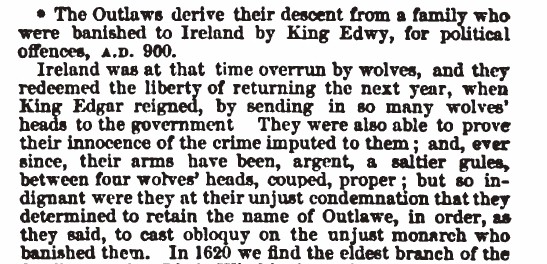

"The Outlaws derive their

descent from a family who were banished to Ireland by King Edwy, for political

offences [ 956- 957 AD] . Ireland was at that time

overrun by wolves, and they redeemed the liberty of returning the next year,

when King Edgar reigned, by sending in so many wolves' heads to the government.

They were also able to prove their innocence of the crime imputed to them ;

and, ever since, their arms have been, argent, a saltier gules, between four

wolves' heads, couped, proper; but so indignant were they at their unjust

condemnation that they determined to retain the name of Outlawe, in order, as

they said, to cast obloquy on the unjust monarch who banished them. "

Obloquy - Definition

- a strongly condemnatory utterance : abusive language - Origin

of OBLOQUY - Middle English obloquie, from Anglo-French, from Late Latin obloquium, from obloqui

to speak against, from ob- against + loqui to speak

First Known Use: 15th century

obloquy -

1. Censure or abusive language towards someone, especially when expressed by many.

2. Disgrace resulting from public condemnation.

St. Dunstan's was exiled (along with his followers (Early Outlawe's?) ) by King Edwy in 957 and returns a year later to

support Edgar, matches the "Outlawe" legend.

However Dunstan fleeing to

Belgium (Flanders - (Flee-Anders) ) does not match the story of an "Outlaw" banishment

to Ireland.

When we look at Edgar, we see that he did offer a general pardon in return

for wolves tongues, still no reference to Ireland. We can imagine that these men

may have been exiled with Dunstan and that they escape to Ireland ( Dunstan had

been raised by Irish Monks and may have had connections to Saxon-Irish

settlements ) then heard about the pardon offered by Edgar and returned

with the required number of Wolf tongues.

So in review:

- It can also be established that

King Edwy WAS considered an unjust monarch and was basically pushed out with Edgar

being selected to replace him (along with Dunstan). So, the story does fits.

- I have been looking into Saxon connections to Dubin Ireland during the period of Edwy and Edgar, but have found nothing

specific. It appears though that the Danes in Dublin DID have connections with the

Wessex Saxon's and would have provided refuge for our Outlawe's, since we see later

under King Edgar, a charter in 964 stating Dublin was in his domain (see

below).

- There can be no doubt that there were many wolves in Ireland and that

it was referred to as "Wolf-land".

- ~961 - Edgar DOES publish a decree for a general pardon in return for

wolves heads when he takes power, and does this also for the kingdom in

Wales.

So, what if this legend IS true? Where would our Utlagh group do in the

next hundred years? What would happen to them and what alliances would they

make?

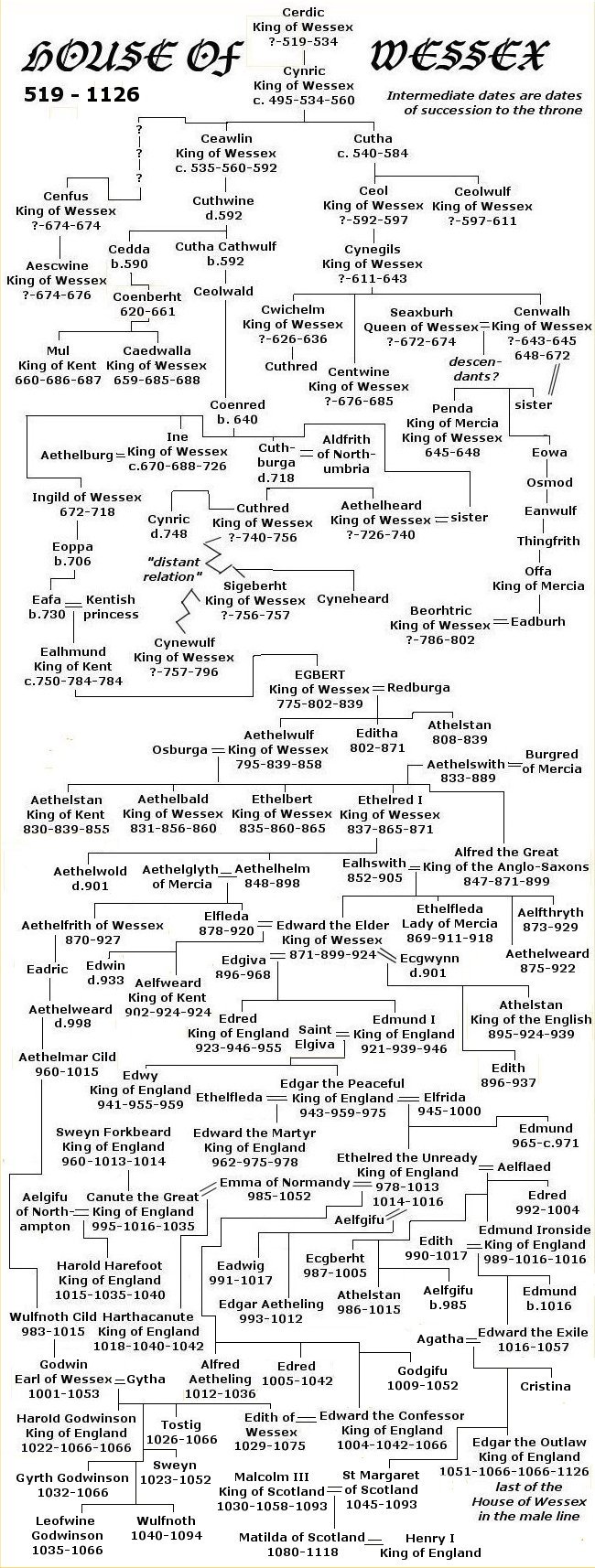

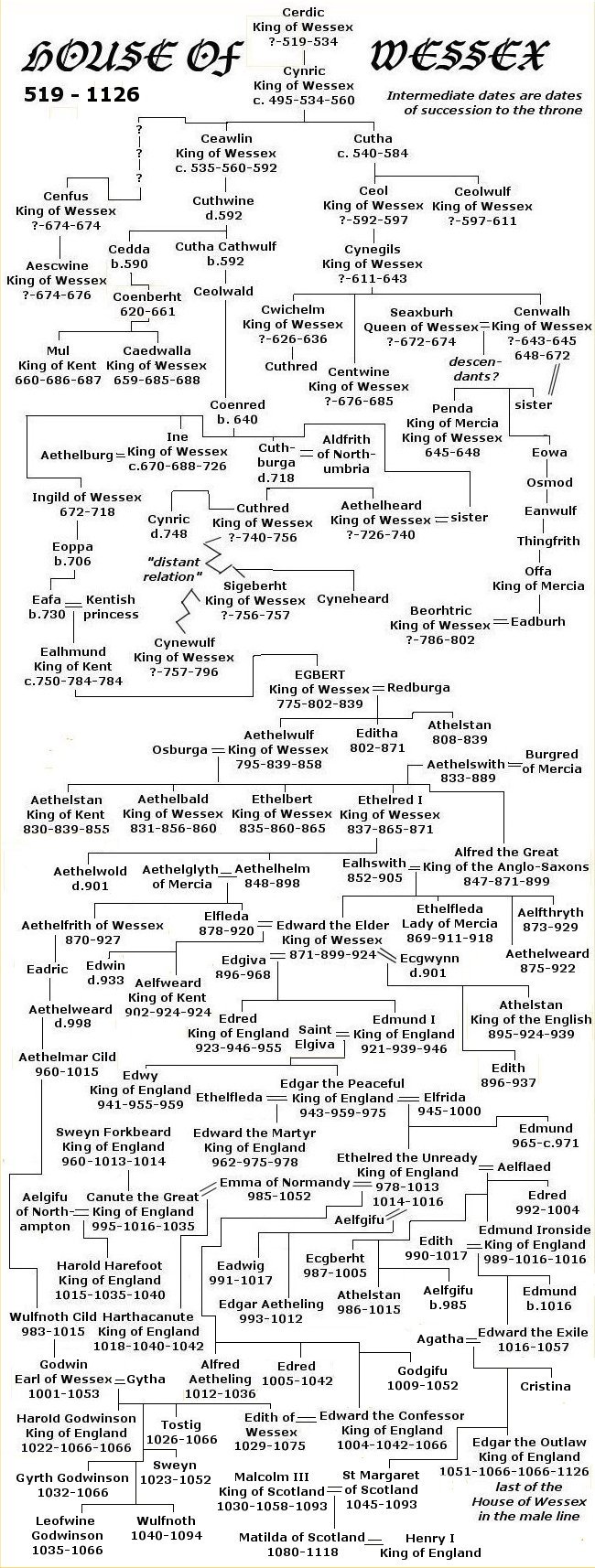

The fact that we find record's of the Vtlaghe's in Kent trying to

retain their lands from the Norman's around 1200 start's to make sense. There

is a direct connection of the House of Wessex to the Kingdom of Kent:

Kingdom

of Kent - (Cent in Old

English, Cantia regnum in Latin)

was a Jutish

colony and later independent kingdom in what is now south

east England.

It was founded at an unknown date in the 5th century by Jutes,

members of a Germanic people from continental Europe, some of whom

settled in Britain after the withdrawal of the Romans.

It was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon

heptarchy, but it lost its independence in the 8th century, when it became a

sub-kingdom of Mercia.

In the 9th century, it became a sub-kingdom of Wessex,

and in the 10th century, it became part of the unified Kingdom

of England which was created under the leadership of Wessex. Its name has

been carried forward ever since as the county

of Kent. List

of monarchs of Kent

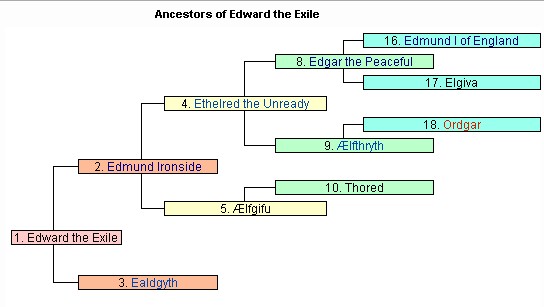

We can see that these men of Wessex and King Edgar goes with the Wessex

"Atheling" line all the way to Edward the Confessor and Edward

the Exile. By the time of Godwin they may have been aligned either way.

If they

were "bodyguards" or "houschurls", they may have left with Æthelred fled to Normandy

when Kiing Cnut took power, or later

left with "Edward the Exile" ( via Kiev and Hungary see below)

or

left with Edward the Confessor for his exile in Normandy.

If they stayed in Wessex (Kent?), they would have probably would have been out of

power for under the Danes and later aligned with the Godwins . Lots of

speculation.

See an alternative story that also matches closely the "Outlawe"

legend story that occurs about a hundred years later in 1052: Earl Godwin and

his son Earl Harold (Godwinson) banishment to Ireland the last Saxon King of

England (of course if that was the story , which is more recent in memory ,

why would you look back to Edwy and Edgar for a legend ?)

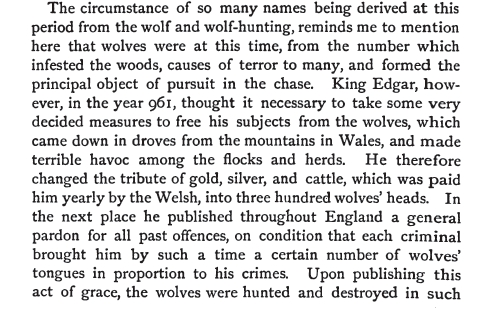

♦Wolves were very numerous in England, King Edgar

unsuccessfully attempted to effect their total destruction by commuting

the punishment of certain crimes into the acceptance of a certain number of

wolves' tongues from each criminal ; their heads

were demanded by him as a tribute particularly 300 annually from Wales, a.d. 961

- which was

paid for three years, but was then discontinued because no more wolves were left

to be killed, a highly improbable story

A complete and universal

English

Dictionary - Edgar contrived a good expedient to clear the

country of wolves, which then were very numerous, and made terrible havoc

among the flocks. Instead of tributes of gold, silver, and cattle, paid him by

the Welsh, he ordered them, in 961, to bring him every year 300 wolves

heads; and

publish, throughout England, a general pardon to all criminals, on condition

they brought him, by such a time, a certain number of wolves tongues, in

proportion to their several crimes ; so that in 3 years time there was

not one left. See also: Transactions of the

Royal Historical

Society Volume 6

A complete and universal

English

Dictionary - Edgar contrived a good expedient to clear the

country of wolves, which then were very numerous, and made terrible havoc

among the flocks. Instead of tributes of gold, silver, and cattle, paid him by

the Welsh, he ordered them, in 961, to bring him every year 300 wolves

heads; and

publish, throughout England, a general pardon to all criminals, on condition

they brought him, by such a time, a certain number of wolves tongues, in

proportion to their several crimes ; so that in 3 years time there was

not one left. See also: Transactions of the

Royal Historical

Society Volume 6

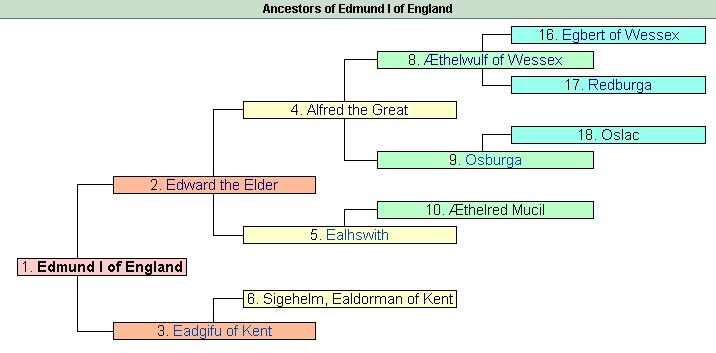

Let's start with the source "The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicles" , it wasn't started until King Alfred (King

Edgars son) but this is the best we have....

A.D. 955. This year died King Edred, on St. Clement's

mass day, at Frome.(41) He reigned nine years and a half; and he rests in the

old minster. Then succeeded Edwy, the son of King Edmund, to the government

of the West-Saxons; and Edgar Atheling, his brother, succeeded to the government

of the Mercians. They were the sons of King Edmund and of St. Elfgiva.

A.D. 956. This year died Wulfstan, Archbishop of York,

on the seventeenth day before the calends of January; and he was buried at

Oundle; and in the same year was Abbot Dunstan driven out of this land over

sea.

A.D. 958. This year Archbishop Oda separated King Edwy and

Elfgiva; because they were too nearly related.

A.D. 959. This year died King Edwy, on the calends of October; and Edgar

his brother took to the government of the West-Saxons, Mercians, and

Northumbrians. He was then sixteen years old. It was in this year he sent

after St. Dunstan, and gave him the bishopric of Worcester; and afterwards the

bishopric of London.

Back to the Wolves stories:

In 968 (?) Eadgar made an expedition into Wales because the Prince of the

North Welsh withheld the tribute that had been paid to the English King since

the time of yhelstan, and, according to William of Malmesbury, laid on the

rebellious Prince a tribute of three hundred wolves' heads for four years,

which was paid for three years, but was then discontinued because no more wolves

were left to be killed, a highly improbable story (Gesta Regum, 155). It

seems as though the Welsh were virtually independent during this reign, for

their Princes do not attest the charters of the English king, and so may be

supposed not to have attended his witenagemots.

A complete and universal English

Dictionary - Edgar contrived a good expedient to clear the

country of wolves, which then were very numerous, and made terrible havoc

among the flocks. Instead of tributes of gold, silver, and cattle, paid him by

the Welsh, he ordered them, in 961, to bring him every year 300 wolves

heads; and

publish, throughout England, a general pardon to all criminals, on condition

they brought him, by such a time, a certain number of wolves tongues, in

proportion to their several crimes ; so that in 3 years time there was

not one left. See also: Transactions of the Royal Historical

Society Volume 6

Born: c. 941 AD

Birthplace: Wessex, England

Died: 1-Oct-959

AD

Cause of death: unspecified

Remains: Buried, Winchester

Cathedral Gender: Male

Occupation: Royalty

Executive summary: King of England 955-59 AD

King Edwy "The Fair", King of the English, was the eldest son of King

Edmund I and Aelfgifu, and succeeded his uncle King

Edred in 955, when he was little more than fifteen years old. He was crowned

at Kingston by Archbishop Odo, and his troubles began at the coronation feast.

He had retired to enjoy the company of the ladies Aethelgifu (perhaps his foster

mother) and her daughter Aelfgifu, whom the king intended to marry. The nobles

resented the king's withdrawal, and he was induced by Dunstan and Cynesige,

bishop of Lichfield, to return to the feast. Edwy naturally resented this

interference, and in 957 Dunstan was driven into exile.

By the year 956 Aelfgifu had become the king's wife, but in 958 Archbishop

Odo of Canterbury secured their separation on the ground of their being too

closely akin. Edwy, to judge from the disproportionately large numbers of

charters issued during his reign, seems to have been weakly lavish in the

granting of privileges, and soon the chief men of Mercia and Northumbria were

disgusted by his partiality for Wessex.

The result was that in the year 957 his brother, the Aetheling Edgar,

was chosen as king by the Mercians and Northumbrians. It is probable that no

actual conflict took place, and in 959, on Edwy's death, Edgar acceded peaceably

to the combined kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria.

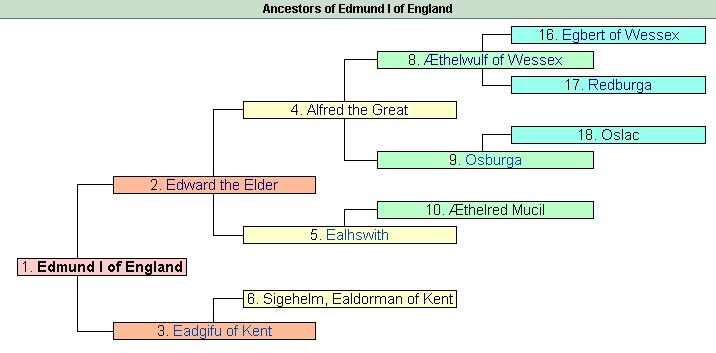

Father: King

Edmund I

Mother: Elgiva

Brother: King Edgar I

Wife: Elgiva (annulled) UK

Monarch 23-Nov-955 to 1-Oct-959

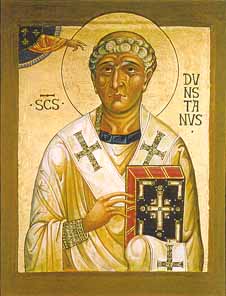

St. Dunstan, the 10th

century English saint, was born near Glastonbury in England. A man of the

church, a great scholar and a statesman, he gave up the worldly pleasures of the

court of King Athelstan to become a monk in Glastonbury. He was known for

his skill with metals, and today is revered by silversmiths as their patron

saint. Out of his ability in metallurgy grew up the legend that Dunstan,

tempted by the Devil while working at his forge, seized the devil's nose with

his red-hot tongs. Dunstan became Abbot of Glastonbury in 945 CE, and made the

monastery famous as a center of learning. He publicly criticized King Edwy,

successor to King Edred. For this he was deprived of his offices and

banished. But he returned to England in 957 and was made bishop of London the

following year.

St. Dunstan, the 10th

century English saint, was born near Glastonbury in England. A man of the

church, a great scholar and a statesman, he gave up the worldly pleasures of the

court of King Athelstan to become a monk in Glastonbury. He was known for

his skill with metals, and today is revered by silversmiths as their patron

saint. Out of his ability in metallurgy grew up the legend that Dunstan,

tempted by the Devil while working at his forge, seized the devil's nose with

his red-hot tongs. Dunstan became Abbot of Glastonbury in 945 CE, and made the

monastery famous as a center of learning. He publicly criticized King Edwy,

successor to King Edred. For this he was deprived of his offices and

banished. But he returned to England in 957 and was made bishop of London the

following year.

In 960 he was elected archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of King

Edgar, who followed Edwy. Dunstan retired to Canterbury in 978 after

Edgar's death and remained there until his death in 988.

Dunstan was canonized for his piety, devotion to learning and dedication to

the institutional church. May 19 is Saint Dunstan's Day.

St. Dunstan's shield carries the bishop's miter to symbolize his service as

Archbishop of Canterbury; the scroll to symbolize his devotion to learning; the

crown to symbolize his life dedicated to the King and Savior of us all; and the

bellows to remind us of his practical vocation as a metallurgist. It may be

viewed on the banner in the sanctuary. St. Dunstan lived c. 925 CE -

988 CE. (CE refers to the Common Era and replaces the old term AD - Anno Domini).

Edgar I the Peaceful (Old

English: Ēadgār; c.

7 August 943 8 July 975), also called the Peaceable, was a king of England

(r. 95975). Edgar was the younger son of Edmund

I of England.

Edgar and Dunstan

Upon Eadwig's death in October 959, Edgar immediately recalled Dunstan

(eventually canonised

as St. Dunstan) from exile to have him made Bishop

of Worcester (and subsequently Bishop

of London and Archbishop

of Canterbury). Dunstan remained Edgar's advisor throughout his reign.

Some see Edgars death as the beginning of the end of Anglo-Saxon

England,

followed as it was by three successful 11th-century conquests two Danish and

one Norman.

Then came the boy-king Edwy,

fifteen years of age; but the real king, who had the real power, was a monk

named Dunstan - a clever priest, a little mad, and not a little proud and

cruel.

Dunstan was then Abbot of Glastonbury

Abbey, whither the body of King Edmund the Magnificent was carried, to be

buried. While yet a boy, he had got out of his bed one night (being then in a

fever), and walked about Glastonbury Church when it was under repair; and,

because he did not tumble off some scaffolds that were there, and break his

neck, it was reported that he had been shown over the building by an angel. He

had also made a harp that was said to play of itself - which it very likely did,

as Aeolian Harps, which are played by the wind, and are understood now, always

do. For these wonders he had been once denounced by his enemies, who were

jealous of his favour with the late King Athelstan, as a magician; and he had

been waylaid, bound hand and foot, and thrown into a marsh. But he got out

again, somehow, to cause a great deal of trouble yet.

The priests of those days were,

generally, the only scholars. They were learned in many things. Having to make

their own convents and monasteries on uncultivated grounds that were granted to

them by the Crown, it was necessary that they should be good farmers and good

gardeners, or their lands would have been too poor to support them. For the

decoration of the chapels where they prayed, and for the comfort of the

refectories where they ate and drank, it was necessary that there should be good

carpenters, good smiths, good painters, among them. For their greater safety in

sickness and accident, living alone by themselves in solitary places, it was

necessary that they should study the virtues of plants and herbs, and should

know how to dress cuts, burns, scalds, and bruises, and how to set broken limbs.

Accordingly, they taught themselves, and one another, a great variety of useful

arts; and became skilful in agriculture, medicine, surgery, and handicraft. And

when they wanted the aid of any little piece of machinery, which would be simple

enough now, but was marvellous then, to impose a trick upon the poor peasants,

they knew very well how to make it; and did make it many a time and

often, I have no doubt.

Dunstan, Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, was

one of the most sagacious of these monks. He was an ingenious smith, and worked

at a forge in a little cell. This cell was made too short to admit of his lying

at full length when he went to sleep - as if that did any good to

anybody! - and he used to tell the most extraordinary lies about demons and

spirits, who, he said, came there to persecute him. For instance, he related

that one day when he was at work, the devil looked in at the little window, and

tried to tempt him to lead a life of idle pleasure; whereupon, having his

pincers in the fire, red hot, he seized the devil by the nose, and put him to

such pain, that his bellowings were heard for miles and miles. Some people are

inclined to think this nonsense a part of Dunstan's madness (for his head never

quite recovered the fever), but I think not. I observe that it induced the

ignorant people to consider him a holy man, and that it made him very powerful.

Which was exactly what he always wanted.

On the day of the coronation of the

handsome boy-king Edwy, it was remarked by Odo, Archbishop of Canterbury

(who was a Dane by birth), that the King quietly left the coronation feast,

while all the company were there. Odo, much displeased, sent his friend Dunstan

to seek him. Dunstan finding him in the company of his beautiful young wife Elgiva,

and her mother Ethelgiva, a good and virtuous lady, not only grossly

abused them, but dragged the young King back into the feasting-hall by force.

Some, again, think Dunstan did this because the young King's fair wife was his

own cousin, and the monks objected to people marrying their own cousins; but I

believe he did it, because he was an imperious, audacious, ill-conditioned

priest, who, having loved a young lady himself before he became a sour monk,

hated all love now, and everything belonging to it.

The young King was quite old enough

to feel this insult. Dunstan had been Treasurer in the last reign, and he soon

charged Dunstan with having taken some of the last king's money. The Glastonbury

Abbot fled to Belgium (very narrowly escaping some pursuers who were sent to put

out his eyes, as you will wish they had, when you read what follows), and

his abbey was given to priests who were married; whom he always, both before and

afterwards, opposed.

But he [Dunstan] quickly conspired with his friend, Odo the Dane, to set

up the King's young brother, Edgar, as his rival for the throne; and, not

content with this revenge, he caused the beautiful queen Elgiva, though a lovely

girl of only seventeen or eighteen, to be stolen from one of the Royal Palaces,

branded in the cheek with a red-hot iron, and sold into slavery in Ireland.

But the Irish people pitied and befriended her; and they said, 'Let us

restore the girl- queen to the boy-king, and make the young lovers happy!' and

they cured her of her cruel wound, and sent her home as beautiful as before. But

the villain Dunstan, and that other villain, Odo, caused her to be waylaid at

Gloucester as she was joyfully hurrying to join her husband, and to be hacked

and hewn with swords, and to be barbarously maimed and lamed, and left to die.

When Edwy the Fair (his people called him so, because he was so young and

handsome) heard of her dreadful fate, he died of a broken heart; and so the

pitiful story of the poor young wife and husband ends! Ah! Better to be two

cottagers in these better times, than king and queen of England in those bad

days, though never so fair!

Then came the boy-king, Edgar,

called the Peaceful, fifteen years old. Dunstan, being still the real king,

drove all married priests out of the monasteries and abbeys, and replaced them

by solitary monks like himself, of the rigid order called the Benedictines. He

made himself Archbishop of Canterbury, for his greater glory; and exercised

such power over the neighbouring British princes, and so collected them about

the King, that once, when the King held his court at Chester, and went on the

river Dee to visit the monastery of St. John, the eight oars of his boat were

pulled (as the people used to delight in relating in stories and songs) by eight

crowned kings, and steered by the King of England. As Edgar was very obedient

to Dunstan and the monks, they took great pains to represent him as the best of

kings. But he was really profligate, debauched, and vicious. He once

forcibly carried off a young lady from the convent at Wilton; and Dunstan,

pretending to be very much shocked, condemned him not to wear his crown upon his

head for seven years - no great punishment, I dare say, as it can hardly have

been a more comfortable ornament to wear, than a stewpan without a handle. His

marriage with his second wife, Elfrida, is one of the worst events of his

reign. Hearing of the beauty of this lady, he despatched his favourite courtier,

Athelwold, to her father's castle in Devonshire, to see if she were

really as charming as fame reported. Now, she was so exceedingly beautiful that

Athelwold fell in love with her himself, and married her; but he told the King

that she was only rich - not handsome. The King, suspecting the truth when they

came home, resolved to pay the newly-married couple a visit; and, suddenly, told

Athelwold to prepare for his immediate coming. Athelwold, terrified, confessed

to his young wife what he had said and done, and implored her to disguise her

beauty by some ugly dress or silly manner, that he might be safe from the King's

anger. She promised that she would; but she was a proud woman, who would far

rather have been a queen than the wife of a courtier. She dressed herself in her

best dress, and adorned herself with her richest jewels; and when the King came,

presently, he discovered the cheat. So, he caused his false friend, Athelwold,

to be murdered in a wood, and married his widow, this bad Elfrida. Six or seven

years afterwards, he died; and was buried, as if he had been all that the monks

said he was, in the abbey of Glastonbury, which he - or Dunstan for him - had

much enriched.

England, in one part of this reign,

was so troubled by wolves, which, driven out of the open country, hid themselves

in the mountains of Wales when they were not attacking travellers and animals,

that the tribute payable by the Welsh people was forgiven them, on condition of

their producing, every year, three hundred wolves' heads. And the Welshmen were

so sharp upon the wolves, to save their money, that in four years there was not

a wolf left.

Our

Patron,

Saint Dunstan, was born in 909 in Baltonsborough, England, of

noble ancestry.

He was educated by Irish monks. He became a Benedictine

monk in 934 and was ordained a priest in 939. From that time until his death

in 988, Dunstan was well known for establishing many great abbeys such as

Glastonbury and Westminster, He was very instrumental in reforming and

rebuilding many of the monasteries destroyed by the Danish invaders. They

became great learning centers, ordaining many monastic bishops for England and

missionaries for Scandinavia.

Dunstan was a person of great holiness and loved

by his disciples and colleagues, kings and commoners alike. He was deeply

involved in the politics of that time and was King Edgars chief advisor in

matters of Church and State from 959 until 975.

Dunstan was a very energetic man and respected as

a creative artist in metal work. He was also a noted musician, playing the

harp and composing several hymns.

Dunstan was immediately venerated as a saint all

over England when he died in 988. He stands as one of the greatest of all the

Archbishops of Canterbury.

Dunstan is a patron saint of metalworkers,

goldsmiths and jewelers

Bishop of Worcester

Archbishop of Canterbury

Patron saint of: Armourers and gunsmiths

Born 909; Died May 19, 988

Feast Day: May 19

Symbol: smith's tongs, and a dove

Saint Dunstan is fairly unusual among Anglo-Saxon saints in that we know

where, if not precisely when, he was born. Dunstan was born in the village of Baltonsborough,

Somerset, just a few miles south of Glastonbury, probably about the year 909

or 910. [Note: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives the birth date as 925]. His

father Heorstan was a Wessex nobleman of royal blood, and his family

connections were to be of great benefit to him in his later career in the

church.

Glastonbury was at that time a popular place for Christian pilgrimage;

folk traditions told that it was the first place of Christian settlement in

Britain, and associated it with Joseph of Arimathea and Jesus himself.

The Abbey at Glastonbury was a centre of learning, and housed scholars from

as far away as Ireland. The young Dunstan was educated at Glastonbury and then

joined his uncle Athelm, Archbishop of Canterbury, at the royal court of King

Athelstan.

Dunstan took to the monastic life much later than most; taking holy orders in

943, when he may already have reached 34 years. Apparently he was at first

disinclined to a life in the church, but a skin disease which he feared might be

leprosy made him change his mind.

After taking orders Dunstan returned to Glastonbury and built himself a

small cell (i.e. a hut) beside the Abbey church. There he lived a simple life of

manual labour and devotion. He soon showed great skill in the arts of

metalworking, and he used his skills to craft bells and vessels for the church.

But his life was not to stay simple for long; Athelstan died, and his

successor Edmund called Dunstan to his court to act as a priest. After a short

period at court, Edmund named Dunstan Abbot of Glastonbury.

So once more Dunstan returned to the place of his birth, this time on a

mission to reinvigorate the abbey. He instituted the strict Benedictine Rule,

rebuilt and enlarged the church buildings, and established Glastonbury as a

leading centre of learning and scholasticism. The effect of Dunstan's reforms,

and in particular his efforts to produce a class of educated clerics, did much

to encourage the growth of monastic settlements throughout Britain.

Dunstan acted as a royal advisor and negotiator for Edmund and his successor

Eadred, and helped establish a period of peace from Danish attack. Unfortunately

in 955 Dunstan's zeal got him into trouble when he reproved young King Eadwig

for moral laxity. Eadwig promptly confiscated Dunstan's property and exiled the

monk.

Dunstan found shelter at the monastery of Ghent, in modern Belgium, but he

was quickly called back to Britain by Edgar, king of Northumbria and Mercia.

Edgar shared Dunstan's monastic zeal, and together they put considerable

energy into monastic reform and expansion. Under Edgar's influence Dunstan

became Bishop of Worcester, and when Eadwig considerately died in 960, Dunstan

was named Archbishop of Canterbury.

In this post Dunstan carried on his work of encouraging scholarship and

monastic settlements. He also oversaw every detail of Edgar's coronation as

king.

It is said that he designed the coronation crown himself, and more

importantly, that he altered the ceremony to put emphasis on the bond between

church and monarch; making the coronation a sacred act, emulating the ceremony

of consecration for priests. Dunstan's coronation ceremony still forms the basis

of royal coronations today.

When Edgar died, Dunstan carried on as advisor to his son Edward, but when

Edward was murdered in 978 to make way for his brother Ethelred, Dunstan retired

from court life. He lived on at Canterbury, delighting in teaching the young and

only rarely troubling to involve himself in the politics of the realm.

When he died in 988 Dunstan was buried in his cathedral, where his tomb was a

popular place of pilgrimage throughout the Middle Ages. Until Thomas a Becket

later eclipsed Dunstan's fame he was the most popular English saint.

Edgar 'the Peaceable', King of England b. 944 Wessex, England d. 8 JUL 975 Winchester, Hampshire, England Axholme Ancestry

... During the rule of his brother, King Edwy, Edgar was chosen by the

Mericians and Northumbrians to be their sovereign. One of his first acts was to

recall the monastic reformer St. Dunstan, whom Edwy had exiled; Edgar

subsequently made Dunstan bishop of Worcester and London and archbishop of

Canterbury. In 959 at the age of sixteen years he succeeded his brother...

Eadgar did not interfere with the Danish districts in England, but granted them

self-government in their districts. This conciliatory policy met with signal

success, and the Danish population lived peacefully under his supremacy. He made

alliance with Otto I, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, and received many gifts

from him. His fame had spread abroad and he was respected by the Kings on the

continent.

Edgar or Eadgar 944-975, King of the English, the younger son of Eadmund the

Magnificent [see Edmund] and the sainted "lfgifu, was born in 944, the year

of his mother's death, for he was twenty-nine at the time of his coronation

in 973 (Anglo-Saxon Chron. sub ann. 972; Flor. Wig. sub ann. 973). He was

probably brought up at the court of his uncle Eadred [see Edred]

(King of Wessex), for his name,

coupled with that of his brother Eadwig [see Edwy], is appended to a charter of

Eadred dated 955 (Kemble, Codex Dipl. 435). After his brother's accession he

resided at his court, and was there on 9 May 957 (ib. 465), when the

insurrection of the north had already broken out. Some time, probably, before

the close of that year he was chosen King by the insurgents. The kingdom was

divided by a decree of the áºitan,' and he ruled over the land north of the

Thames.

He begins to issue charters as King the following year. In a charter of

958 he styles himself `king of the Angles and ruler of the rest of the peoples

dwelling round' (ib. 471); in a charter of the next year `king of Mercia,'

with a like addition (ib. 480); and in another charter, granted probably

about the same time, `king of the Mercians, Northumbrians, and Britons'

(Wells Chapter MSS.).

As he was now scarcely past childhood he must have been little more than a

puppet in the hands of the northern party. As soon as he was settled on the

throne he sent for Dunstan [q.v.], who was then in exile, and who from that

time became his chief minister and adviser. The other leading men of his

party were Oskytel, archbishop of York; Tfhere, ealdorman of Mercia; Brihtnoth

[q.v.], ealdorman of Essex; and yhelstan, the `half-king,' ealdorman of East

Anglia, whose wife, "lfwen, was the young king's foster-mother (Historia

Ramesiensis, 11), a connection that may have had a curious bearing on the

rivalry between him and his elder brother, for it has been suggested that "thelfgifu,

the mother of Eadwig's wife, and a person of great weight at his court, stood in

the same relation to the West-Saxon King (Robertson, Essays, 180, 201).

...

On the death of Edwy [q.v.] or Eadwig in October 959 Eadgar, who was

then sixteen, was chosen King by the whole people (Flor. Wig.), and

succeeded to the kingdom of the West-Saxons, as well as of the Mercians and

Northumbrians (A.-S. Chron.). His reign, though of considerable historical

importance, does not appear to have been eventful. It was a period of national

consolidation, peace, and orderly government. Much of the prosperity of the

reign should certainly be attributed to the wisdom of Dunstan, archbishop of

Canterbury (960-988), who served the King as well and faithfully as he had

served his uncle Eadred.

In 968 (?) Eadgar made an expedition into Wales because the Prince of the

North Welsh withheld the tribute that had been paid to the English King since

the time of yhelstan, and, according to William of Malmesbury, laid on the

rebellious Prince a tribute of three hundred wolves' heads for four years,

which was paid for three years, but was then discontinued because no more wolves

were left to be killed, a highly improbable story (Gesta Regum, 155). It

seems as though the Welsh were virtually independent during this reign, for

their Princes do not attest the charters of the English king, and so may be

supposed not to have attended his witenagemots.

Eadgar's relations with the Danish parts of the kingdom are of more

importance. From the time of the death of Eric Haroldsson and the skilful

measures taken by Eadred and Dunstan to secure the pacification of Northumbria, the

northern people had remained quiet until they had joined in the revolt against

Eadwig. By the election of Eadgar and the division of the kingdom they broke

off their nominal dependence on the West-Saxon throne. Now, however, Eadgar

himself had become King of the whole land, and Wessex was again the seat of

empire. It was probably this change that in 966 led to an outbreak in

Northumbria. The disturbance was quelled by Thored, the son of Gunner,

steward of the king's household, who harried Westmorland, and Eadgar sought to

secure peace by giving the government of the land to Earl Oslac. It is said,

though not on any good authority, that as Kenneth of Scotland had taken

advantage of this fresh trouble in the north to make a raid upon the country,

Eadgar purchased his goodwill, at least so it is said, by granting him Lothian,

or northern Bernicia, an English district to the south of the Forth, to be held

in vassalage of the English crown. (This grant, which has been made the subject

of much dispute, has been fully discussed by Dr. Freeman, Norman Conquest, i.

610-20; and E. W. Robertson, Scotland under her Early Kings, ii. 386 sq.).

...

This self-government was granted, Eadgar tells the Danes, as a reward `for the

fidelity which ye have ever shown me' (Thorpe, Ancient Laws, 116, 117). The two

peoples, then, lived on terms of equality each under its own law, though,

indeed, the differences between the systems were trifling, and this arrangement,

as well as the good peace Eadgar established in the kingdom, was no doubt the

cause that led the áºitan' in the reign of Cnut to declare the renewal of Ãadgar's

law' [see under Canute]. Besides this policy of non-interference he favoured

men of Danish race, and seems to have adopted some of their customs. The steward

of his household was a Dane, and a curious notice in the `Chronicle'

concerning a certain king, Sigferth, who died by his own hand and was buried at

Wimborne, seems to point to some Prince of Danish blood who was held in honour

at the English court. Offices in Church and state alike were now open to the

northern settlers. While, however, Eadgar was thus training the Danes as good

and peaceful subjects, his policy was looked on with dislike by Englishmen

of old-fashioned notions, and the Peterborough version of the `Chronicle'

preserves a song in which this feeling is strongly expressed. The King is

there said to have `loved foreign vices' and `heathen manners,' and to have

brought òutlandish' men into the land.

...

At the date of his coronation at Bath, Eadgar was in his thirtieth

year. He is said to have been short and slenderly made, but of great strength

(ib. 156), `beauteous and winsome' (A.-S. Chron.). His personal character, the

events of his life, and the glories of his reign made a deep impression on the

English people. Not only are four ballads, or fragments of ballads, relating

to his reign preserved in the different versions of the national chronicle, but

a large mass of legends about him, originally no doubt contained in gleemen's

songs, is given by William of Malmesbury. He is represented in somewhat

different lights. All contemporary writers save one speak of him in terms of

unmixed praise; the one exception, the Peterborough chronicler, while dwelling

on his piety, his glory, and his might, laments, as we have seen, his love of

foreigners and of foreign fashions and evil ways.

Eadred - The British Chronicles - Google Books

- English Monarchs - Kings and Queens of England -

Edred. - WikijuniorKings and Queens of England-The Anglo-Saxons - Wikibooks, collection of open-content textbooks

King Edgar's connection to Dublin Ireland:

Antuiquity, name and inhabitants of Dublin

...

The next antient authority concerning Dublin, is king

Edgar's charter, called Oswald's-law, dated at Gloucester in the year 964;

the preface to which runs thus in English:

"By the abundant mercy of God, who thundereth from on

high, and is King of kings, and Lord of lords, I EDGAR, king of the English,

and emperor and lord of all the kings of the islands of the ocean, which lie

round Britain, and of all the nations included in it, give thanks to the

omnipotent God, my King, who hath so greatly extended my empire, and exalted it

above the empire of my ancestors, who though they obtained the monarchy of all

England, from the reign of Aethelstan, who, first of all the kings of

the English, by his arms, subdued all the nations inhabiting Britain, yet none

of them ever attempted to stretch its bounds beyond Britain. But divine

Providence hath granted to me, together with the empire of the English, all the

kingdoms of the islands of the Ocean, with their fierce kings, as far as Norway,

and the greatest part of Ireland, with its most noble city of Dublin; "all

which by the most propitious grace of God, I have subdued under my power."

Some writers have called this charter in question; but they

are such, who repine that the English should have any footing here at all; not

duly reflecting, what happiness they enjoy under the mild administration of the

best of laws, compared with the misery they suffered while their

own rude customs prevailed.

The Saxon annals relate, "that the power of Edgar was

so great, by the means of a considerable fleet and army which he supported, that

the kings of Wales, Ireland, and the isle of Man, were obliged to swear

allegiance to, and acknowledge him for their sovereign:" which might

have given rise to those expressions in his charter relating to his conquest of

a great part of Ireland.

That some of the Anglo-Saxon kings had a dominion over the

city of Dublin, and perhaps over other parts of Ireland, seems to be clearly

evinced, by a coin of king Ethelred, next successor but one to Edgar, the

legend on the reverse of which expresseth the mint-master's name, and the place

where it was struck to be at Dyfelin.

Now Ethelred could not assume this mark of

sovereignty, of minting money within the dominions of a prince, who did not

acknowledge him as his superior lord and this casts some light over the

before-recited charter of king Edgar.

'Tis certain that the Danes, under princes of their own,

held the actual government of Dublin during the reigns of both these princes yet

it is no way improbable, that they held that city by homage and tribute, though

no mention is made of it by historians. This circumstance elucidates all the

difficulties in Edgar's charter, the Saxon annals, and the coin of Ethelred

before mentioned, which is at present in the possession of a gentleman of the

physico-historical society. Thus far of the antiquity of the city of Dublin.

Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons - Bernicia

|

918/919

|

A powerful Norse-Irish dynasty from Dublin

seizes control of York,

potentially destroying the slow Anglo-Saxon recovery of the region.

Ealdred is driven back into his own lands, suggesting a greater level of

authority has been enjoyed by Bamburgh until this date.

|

|

920 - 921

|

At the same time that Ragnald, king of Dublin

and York,

accepts Edward, king of Wessex,

as father and lord, Ealdred does the same.

|

|

927

|

Athelstan marches north after subduing the Scandinavian

kingdom of York

and expels Ealdred (perhaps because he is a rival for the throne at York).

Ealdred becomes the king's man and is reinstated.

|

|

930 - 963

|

Oswulf / Osulf

|

Son. Helped defeat Eric Bloodaxe in York.

Earl of York

(954-963).

|

|

954

|

A coalition of northern forces tributary to Eadred of

Wessex

defeats Eric Bloodaxe, king of York,

in battle, due in no small part to Oswulf's vital allegiance. Northumbria

falls under the rule of the kings of England

and is administered by Oswulf.

|

|

955 - 959

|

There is a successional rift between King Edred's two

sons, Edwy and Edgar. The latter takes control of Mercia

and Northumbria, while Edwy rules in the south until his death in 959.

Edgar then seizes complete control and becomes the second king of England.

|

|

959 - 960

|

Oswulf is signing charters as dux and then eorl

of York,

but following his death in 963, the territories under his control are

divided, with one Oslac being handed York by King Edgar the Peaceful of England,

while Oswulf's son succeeds him in Bamburgh.

|

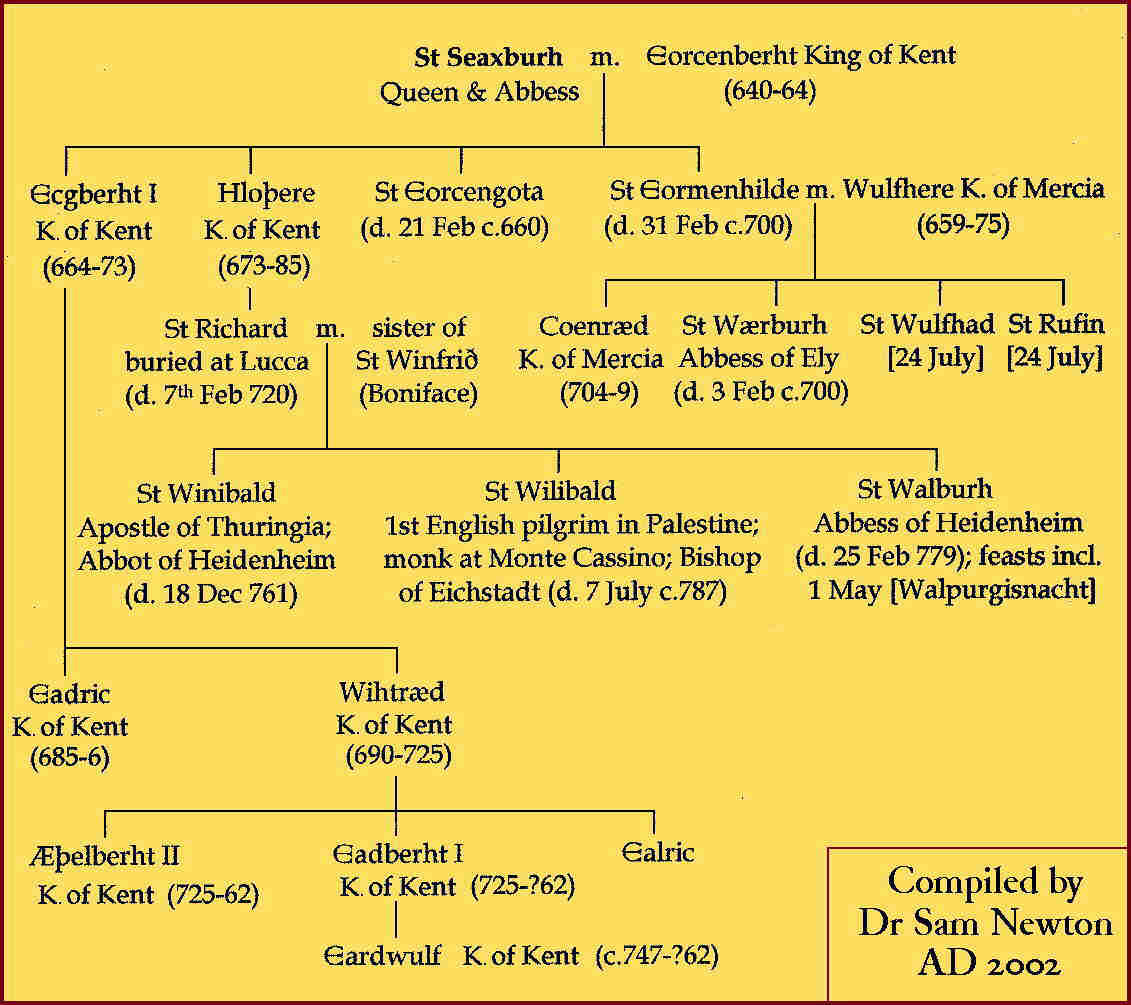

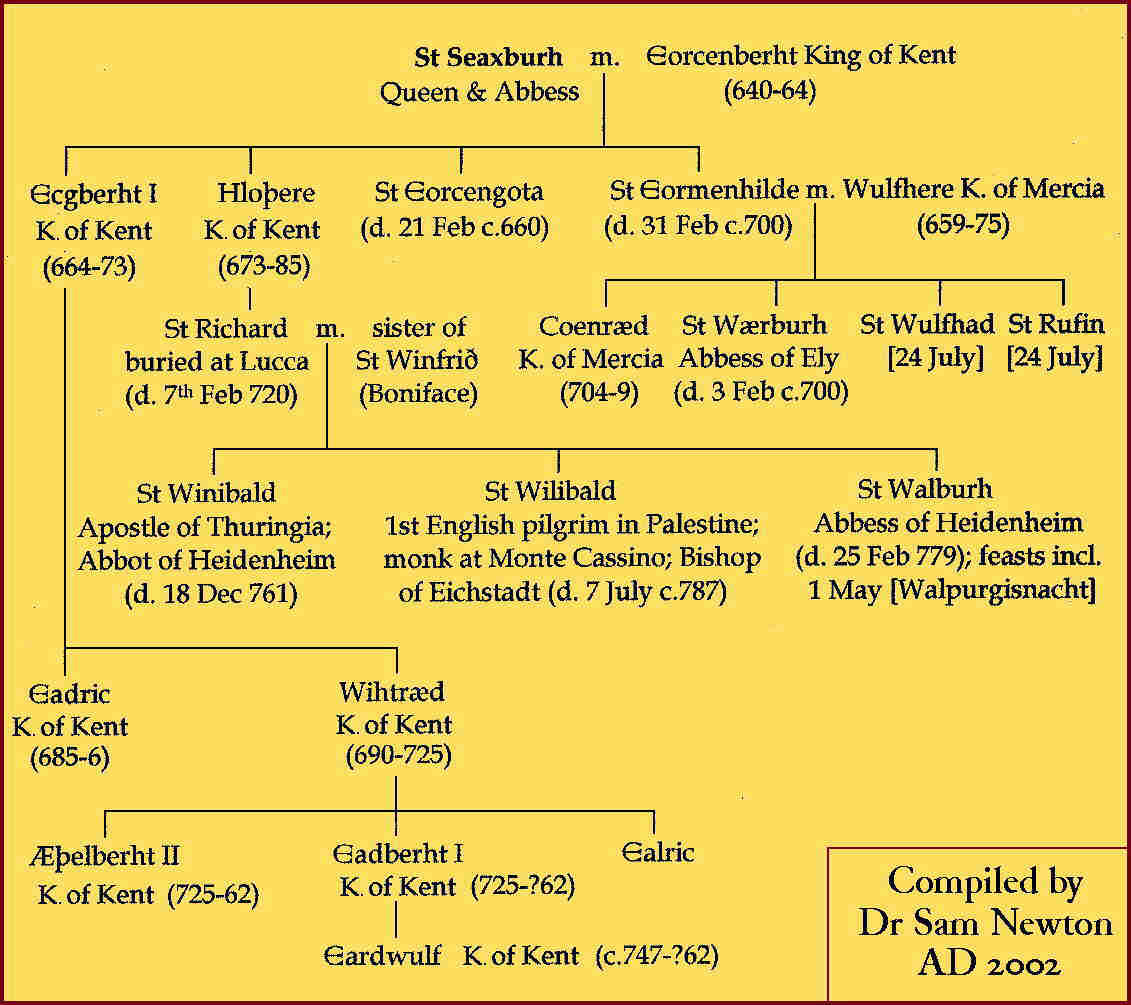

The Wuffing connection to House of Wessex: St

Seaxburh - the Wuffing princess Seaxburh - [also known as Saxburga

or Sexburga]

According to Bede, Seaxburh was the eldest daughter of Onna (HE III, 8). Through

her marriage to Eorconberht, King of Kent (640-64), she was to become the

mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother of kings and saints.

Her children from the marriage include Ecgberht I, King of Kent (664-73),

Hlothere, King of Kent (673-85), St Eorcongota [21st Feb], and St Eormenhilda

[13th Feb]

....

Although subsequent genealogical relations are uncertain, St Seaxburhs

line may have continued through to Ecgberht II of Kent, who ruled c.765-84,

and Ealhmund, king of Kent c.785. The latter was the father of Ecgberht, king of

Wessex (802-839), grandfather of Ælfred the Great.

This would mean that Seaxburh would embody a genealogical link between the

Wuffings and the West Saxon dynasty, from whom our present royal family is

descended.

For a discussion of other possible connections between the Wuffings and the West

Saxon kings in the ninth century, see Chapter

Six of Sam Newton's book on Beowulf.

List of monarchs of Wessex

Death and succession

On 26 May, 946, Edmund was murdered by Leofa, an exiled thief, while

celebrating St Augustine's Mass Day in Pucklechurch

(South Gloucestershire).[4]

John

of Worcester and William

of Malmesbury add some lively detail by suggesting that Edmund had been

feasting with his nobles, when he spotted Leofa in the crowd. He attacked the

intruder in person, but in the event, Edmund and Leofa were both killed.[5]

Edmund's sister Eadgyth,

wife to Otto

I, died (earlier) the same year, as Flodoard's

Annales for 946 report.[6]

Edmund was succeeded as king by his brother Edred,

king from 946 until 955. Edmund's sons later ruled England as:

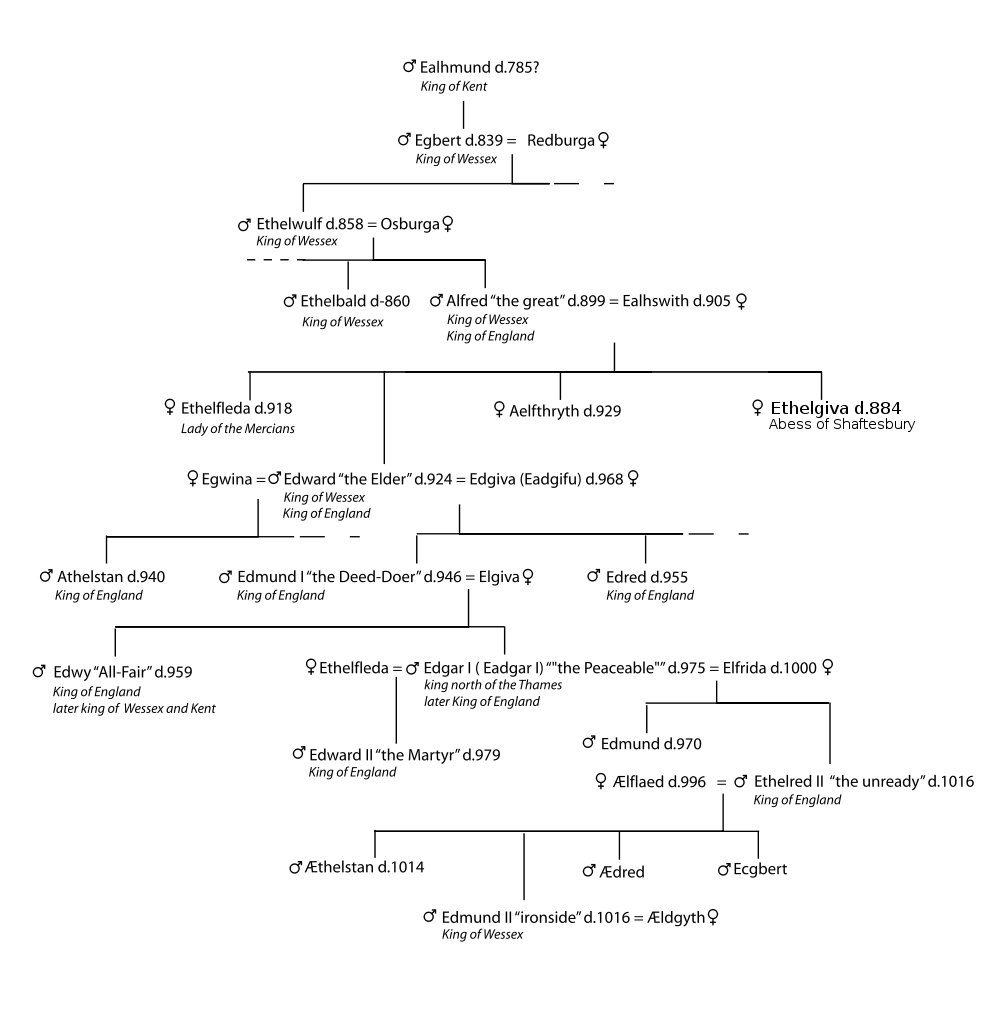

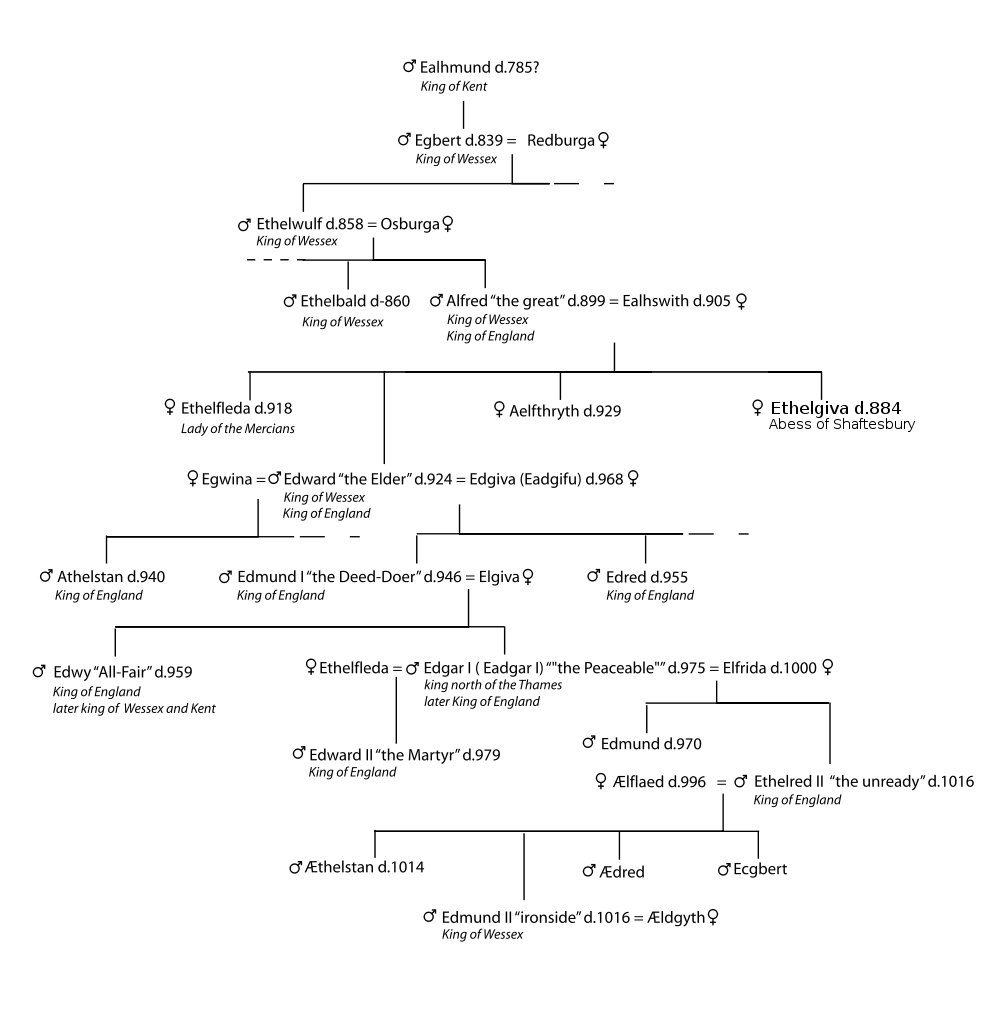

So after Edgar we have:

Edward the Martyr

- (Old

English: Eadweard) (c. 962 18 March 978) was king

of the English from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the

eldest son of King Edgar,

but not his father's acknowledged heir.

On Edgar's death, the leadership of England was contested, with some supporting

Edward's claim to be king and other supporting his much younger half-brother Æthelred

the Unready. Edward was chosen as king and was crowned by his main clerical

supporters, Archbishops Dunstan

and Oswald

of Worcester.

Then we have:

Æthelred the Unready

- or Æthelred II[1]

(c. 968 23 April 1016), was king

of the English (9781013 and 10141016). He was son of King

Edgar and Queen Ælfthryth.

Æthelred was only about 10 (no more than 13) when his half-brother Edward

was murdered. Æthelred was not personally suspected of participation, but as

the murder was committed at Corfe

Castle by the attendants of Ælfthryth, it made it more difficult for the

new king to rally the nation against the invader, especially as a legend of St

Edward the Martyr soon grew. Later, Æthelred ordered a massacre of Danish

settlers in 1002 and also paid tribute, or Danegeld,

to Danish leaders from 991 onwards. His reign was much troubled by Danish Viking

raiders. In 1013, Æthelred fled to Normandy

and was replaced by Sweyn,

who was also king of Denmark. However, Æthelred returned as king after Sweyn

died in 1014.

"Unready" is a mistranslation of Old English unræd (meaning

bad-counsel) a twist on his name "Æthelred" (meaning

noble-counsel).

Then :

Edmund Ironside

- (or Edmund II) (Old

English: Eadmund) (c.

988/993 30 November 1016) was king

of the English from 23 April to 30 November 1016. The cognomen

"Ironside" refers to his efforts to fend off a Viking

invasion led by Cnut

the Great. His authority was thereafter limited to Wessex, or the area south

of the River

Thames. The north was controlled by Cnut, who became "king of all

England" upon Edmund's death.

Edmund had two children by Ealdgyth: Edward

the Exile and Edmund. Cnut

the Great ordered them both sent to Sweden,

to be murdered, but they were sent on to Kiev

and ended up in Hungary.

So Cnut and the Danes take over and Finally:

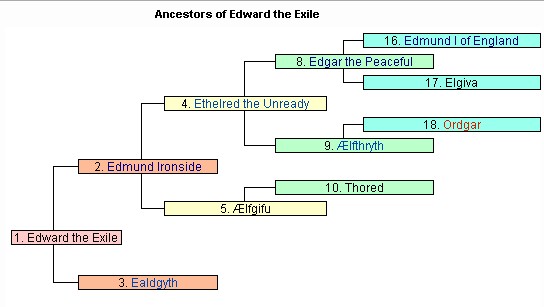

Edward the Exile

- (The Outlaw) - (1016 Late August 1057), also called Edward

Ætheling, son of King

Edmund

Ironside and of Ealdgyth.

After the Danish

conquest of England in 1016 Canute

had him and his brother, Edmund, exiled to the Continent. Edward was only a few

months old when he and his brother were brought to the court of Olof

Skötkonung, (who was either Canute's half-brother or stepbrother), with

instructions to have the children murdered. Instead, the two boys were secretly

sent to Kiev, where

Olof's daughter Ingigerd

was the Queen. Later Edward made his way to Hungary,

probably in the retinue of Ingigerd's son-in-law, András

in 1046, who he supported in his successful bid for the Hungarian throne.

On hearing the news of his being alive, Edward

the Confessor recalled him to England in 1056 and made him his heir.

Edward offered the last chance of an undisputed succession within the Saxon

royal house. News of Edward's existence came at time when the old

Anglo-Saxon Monarchy, restored after a long period of Danish domination, was

heading for catastrophe. The Confessor, personally devout but politically weak,

was unable to make an effective stand against the steady advance of the powerful

and ambitious sons of Godwin,

Earl of Wessex. From across the Channel William,

Duke of Normandy also had an eye on the succession. Edward the Exile

appeared at just the right time. Approved by both king and by the Witan,

the Council of the Realm, he offered a way out of the impasse, a counter both to

the Godwins and to William, and one with a legitimacy that could not be readily

challenged.

Edward, who had been in the custody of Henry

III, the Holy Roman Emperor, finally came back to England at the end of

August 1057. But he died within two days of his arrival.

Then we have:

Edward the Confessor

- (Old

English: Ēadƿeard se Andettere;

French:

Édouard le Confesseur; c. 1003 5

January 1066),[1]

son of Æthelred

the Unready and Emma

of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon

kings

of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House

of Wessex, ruling from 1042 to 1066 (technically the last being Edgar

the Ætheling who was proclaimed king briefly in late 1066

Edward had succeeded Cnut's

son Harthacnut,

restoring the rule of the House of Wessex after the period of Danish rule since

Cnut had conquered England in 1016. When Edward died in 1066 he had no son to

take over the throne so a conflict arose as three men claimed the throne of

England.

Edward was born c. 1003 in Islip,

Oxfordshire. Edward and his brother Alfred

were sent to Normandy for exile by their mother. Æthelred died in April 1016,

and he was succeeded by Edward's older half brother Edmund

Ironside, who carried on the fight against the Danes until his own death

seven months later at the hand of Canute, who next became king and married

Edward and Alfred's mother, Emma. According to Scandinavian tradition,

Edward, by then back in England, fought alongside his brother, and distinguished

himself by almost cutting Canute in two, although as Edward was at most thirteen

years old at the time, the story is highly unlikely.

Edward and his brother Alfred unsuccessfully attempted to depose Harold in

1036. Edward then returned to Normandy, but Alfred was captured by Godwin,

Earl of Wessex who then turned him over to Harold

Harefoot, who blinded by forcing red hot pokers into his eyes to make him

unsuitable for kingship. Alfred died soon after as a result of his wounds. This

murder of Edward's brother is thought to be the source of much of Edward's later

hatred for the Earl and one of the primary reasons for Godwin's banishment in

autumn 1051;

The Anglo-Saxon lay and ecclesiastical nobility invited Edward back to

England in 1041; this time he became part of the household of his

half-brother Harthacnut

(son of Emma and Canute),

and according to the Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle was sworn in as king alongside him. Following Harthacnut's

death on 8 June 1042, Edward ascended the throne

Edward had married Godwin's daughter Edith

on 23 January 1045, but the union was childless.

Tour Scotland, Scottish

Anecdotes. -

The power of Edgar "the Peaceful" was such that as a sign of his power,

Edward was

rowed down the River Dee with the oars manned by 8 Kings of tributary kingdoms.

English Monarchs - Kings and Queens of England -

Edgar the Peaceful. - Edgar was a very small man, recorded as

being less than five feet tall, although possessing great personal magnetism. The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes him as being handsome. Following

his coronation, Edgar travelled north to Chester, where he met with eight

sub-Kings of Britain whom he had summoned. Among them was Kenneth,

King of Scots and his son Malcolm, King of the Cumbrians along with six

others, including the Princes of Wales.

In a demonstration of the power of Wessex, Edgar was rowed up the River

Dee to the Monastery of St. John the Baptist, by all eight sub-Kings,

attended by a great concourse of nobles. The entire occasion represented an

assertion of Saxon supremacy over the Celts of England, Scotland and Wales.

Tour Scotland, Scottish

Anecdotes.

The Guinness Book of Records shows that the tallest Scotsman and the tallest "true"

giant was Angus Macaskill. Born on the island of Berneray off the island of

Harris in 1825, Macaskill was 7ft 9in (2.36m) tall. He was also strong,

reputedly able to lift a hundredweight (50kg) with two fingers and hold it at

arms length for ten minutes. He died on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, in

1863. A cairn on Berneray commemorates him.

The blue paint that Pictish, and later the Scottish warriors wore in battle was a hallocinogen.

It was was the mold from rye.

Scotland is the only country in Europe that the Romans could not conquer.

The Scots were the tallest race in Europe, according to the 1909 Census. But the carnage of

WWI changed that. By the 1930s, the average height of men in Scotland had

been reduced by 9 inches.

Our

Patron, Saint Dunstan, was born in 909 in Baltonsborough, England, of

noble ancestry. He was educated by Irish monks. He became a Benedictine

monk in 934 and was ordained a priest in 939. From that time until his death

in 988, Dunstan was well known for establishing many great abbeys such as

Glastonbury and Westminster, He was very instrumental in reforming and

rebuilding many of the monasteries destroyed by the Danish invaders. They

became great learning centers, ordaining many monastic bishops for England and

missionaries for Scandinavia.

Our

Patron, Saint Dunstan, was born in 909 in Baltonsborough, England, of

noble ancestry. He was educated by Irish monks. He became a Benedictine

monk in 934 and was ordained a priest in 939. From that time until his death

in 988, Dunstan was well known for establishing many great abbeys such as

Glastonbury and Westminster, He was very instrumental in reforming and

rebuilding many of the monasteries destroyed by the Danish invaders. They

became great learning centers, ordaining many monastic bishops for England and

missionaries for Scandinavia.

From "

From "

St. Dunstan, the 10th

century English saint, was born near Glastonbury in England. A man of the

church, a great scholar and a statesman, he gave up the worldly pleasures of the

court of King Athelstan to become a monk in Glastonbury. He was known for

his skill with metals, and today is revered by silversmiths as their patron

saint. Out of his ability in metallurgy grew up the legend that Dunstan,

tempted by the Devil while working at his forge, seized the devil's nose with

his red-hot tongs. Dunstan became Abbot of Glastonbury in 945 CE, and made the

monastery famous as a center of learning. He publicly criticized King Edwy,

successor to King Edred. For this he was deprived of his offices and

banished. But he returned to England in 957 and was made bishop of London the

following year.

St. Dunstan, the 10th

century English saint, was born near Glastonbury in England. A man of the

church, a great scholar and a statesman, he gave up the worldly pleasures of the

court of King Athelstan to become a monk in Glastonbury. He was known for

his skill with metals, and today is revered by silversmiths as their patron

saint. Out of his ability in metallurgy grew up the legend that Dunstan,

tempted by the Devil while working at his forge, seized the devil's nose with

his red-hot tongs. Dunstan became Abbot of Glastonbury in 945 CE, and made the

monastery famous as a center of learning. He publicly criticized King Edwy,

successor to King Edred. For this he was deprived of his offices and

banished. But he returned to England in 957 and was made bishop of London the

following year.