|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

From "A visitation of the seats and arms of the noblemen and gentleman of Great Britain by Bernard Burke" (section about the Heddings) it says ;

"The Outlaws derive their descent from a family who were banished to Ireland by King Edwy, for political offences A.D.900. [More likely ~955-957AD see Dunstan link] [See: Was the Outlawe's banishment associated with Saint Dunstan? (patron Saint of Goldsmiths)]

Ireland was at that time overrun by wolves, and they redeemed the liberty of returning the next year, when King Edgar reigned, by sending in so many wolves' heads to the government.

They were also able to prove their innocence of the crime imputed to them ; and, ever since, their arms have been, argent, a saltier gules, between four wolves' heads, couped, proper; but so indignant were they at their unjust condemnation that they determined to retain the name of Outlawe, in order, as they said, to cast obloquy on the unjust monarch who banished them.

Regardless of other explanations proposed - We have seen from the earliest records from 1190-1210 AD that the clan of Outlawe - "Vtlaghe's" were based in Kent/(and south London?) trying to keep their lands from the Normans. And we know that Harold's brother Leofwine Godwin (died at Hastings) was "Earl of Kent" in 1066.

1198 - Philip and Henry and Richard and William and Jordan, sons

of Vtlag’ - Kent

Pipe Rolls - John 1198

1200~1212 - De

Helia Vtlagh (of

Elham)

- Rents due about Mildelton - (Milton

Kent) (Elham Canterbury,

Kent)

1200~1212 - Haghenild

Vtlaghe - lands

of Newton and Newington - Heirs: Hildith , Simon,

and Adam, and Henry and Roger son of Thomas -

( Canterbury, Kent )

It

is interesting that

Lewin is a another name for Leofwine and that later the Outlaw's

donated "Lewin's Mead " in Bristol to Margam Abbey.

It was from Bristol in 1051 that Leofwine and Harold Godwinson left for Dublin

Ireland during their Banishment :

1210 - Margam

Abbey - John, son of Ralph Utlage, the

meadow of Leowine, Lewin's-mead, St. James' - Bristol

So we have a reasonable expectation at least that at the time of Hastings, the Vtlag's were men of Kent, loyal to Harold's brother Leofwine.

So here I would like to suggest another explanation , I have found an early story that MATCHES the Outlaw story very well...:

1. Time period Not 955 but AD 1051 AD - Not King Edwy/Edgar but Edward the Confessor and Earl Godwin / Earl Harold (Godwin)

2. When Earl Harold and his brother Leofwine (Godwin) are banished to Ireland, still in the kings domain, it is with the idea that he is hostage to keep his father Earl Godwin from acting/fighting, his father has the money and power to put up a fight.

"In early

October Godwin and the rest of his sons were declared outlaws and given five

days to leave the country. The men of Dover were left unpunished. Godwin,

his wife Gytha, and his sons Swein, Tosti and Gyrth boarded ship at Bosham and

left for Flanders. Harold and Leofwine Godwinson sailed from Bristol for the

Norse stronghold of Dublin in Ireland. There, after a stormy crossing, they

were welcomed into the court of Diarmait Mac Mæl-Na-Mbo, King of Leinster"

Also he is banished and stays in Ireland a year or less (the winter of

1051-1052) which matches the Outlaw

story. Followers (thegns / fighters) for Harold would have been banished with

him. Among these followers of Harold and the Godwin's were probably our future "Outlaw"

clan.

We see from the Wuffings Saxon symbology that the cult of the Wolf and association of the outlaw that these men may have been his personal (soldier) guard.

or another alternative they were Norse-Irish Mercenaries from Wolf-land (Ireland) :

During Harold's time with the Diarmid, the king (King of Leinster -

Ireland), possibly with help from the Godwinsons and their followers, expelled the Norse-Irish King Eachmargach from Dublin and replaced him with his son,

Murchad. Dublin was full of Viking mercenaries, and the new king allowed the Godwinsons to freely recruit them for the coming struggle with King

Edward.

3. An outlaw was said to bear a

"wolf's head," Earl Harold returns with many "wolves heads", other

"outlaw" exiles he has recruited to return with him to force the

king's hand to accept him and his followers back.

4. In recognition that they were one of the many "wolves heads", the arms have a red saltire between four wolve's heads severed (one of the many wolves heads), that forced the kings hand and (A demi-wolf, pierced through the side with an arrow - The Demi-wolf symbolizes the unjust king that is now wounded with a golden arrow of truth) You wouldn't use a golden arrow on a real wolf !

Alternatively : The gold arrow may symbolize Harold II himself (who was said to be killed by an arrow in the eye).

So followers in Earl Harold's group honored him by carrying this new

Outlaw Shield as being one of many of "Harold's Wolves" from Ireland

"Wolf-land" .

Godwin, Earl of Wessex, was one of the most prominent figures in late Anglo-Saxon England, and many texts preserve stories of his life.

This narrative is the earliest extended account of outlawry in English Literature. It introduces a number of themes to the outlaw tradition: the conflict between a Saxon nobleman and corrupt Norman royal officials, false accusations by a powerful cleric, outlawry and banishment of the hero, the hero's return with an armed force, popular support of the people, and reconciliation with the king.

History of Anglo-Saxons, by Sir Francis Palgrave. [ Understand this is written by the Norman victors ! ]

HISTORY OF THE ANGLO-SAXONS

Earl Godwin gathered his forces far and wide, and so did his sons, Earl Sweyne and Earl Harold...

This witenagemot was accordingly held; but the interval of time had tended greatly to the disadvantage of Godwin (A.D. 1051-1052). His forces were melting away—many of his followers abandoned him. The king had been actively employed in raising the forces of such of the parts adjoining the Thames as were under his own actual control; and when the witan met,

the first measure which they adopted was an adjudication that Sweyne should be outlawed. This was a heavy doom. An outlaw was said to bear a "wolf's head," that is to say, he was declared as much out of the protection of society as the savage animal; any one might slay him with impunity; and therefore sentence of death was virtually passed against the earl.Godwin and his sons, so late the "king's darlings," were

now exiles; and, "wonderful would it have been thought," in the

words of the Saxon chronicle, "if any one had said before, that matters

would have come to this pass." The old earl and his son Sweyne sailed to

Flanders, to Earl Baldwin's country; and they had a ship full of treasure

with them, to purchase a hearty and good welcome from the Flemings. Harold

crossed to Ireland, and he was so far favoured, as to be allowed to remain in

that country under the king's protection. This fact should be remarked,

because it seems to show that he was not considered as being out of the

king's dominions; or, in other words, that the opposite coast of Ireland was

part of Edward's realm.

...

This calm did not last long—Godwin, as you will recollect, was in Flanders,

with a ship full of treasure, and gathering together a fleet, he attacked the

southern coast, and laid the country under contribution (A.D. 1052). King Edward

was not unprepared; he and his witan apprehended that such an attack was

meditated, and they had taken counsel how they might best avert the danger. They

had, therefore, sent a fleet with orders to blockade the Flemish ports, and

prevent the escape of Godwin. This naval force was placed under the command of

Godwin's personal enemies: Earl Ralph, the Frenchman, and Earl Odda, who

possessed the best portion of Godwin's dominions. But the Earl was on the alert;

the weather favoured him; he outwitted his adversaries, and the king's affairs

were so badly managed, that the fleet returned home, and the expedition was

wholly dispersed.

Harold, on his part, was full of activity; he sailed from Ireland, and joining his forces to those of his father, they proceeded to rouse their adherents. The mariners belonging to Hastings appear to have been the first who joined them. Kent, Sussex, Surrey, and Essex followed the same example, besides many other districts and shires—all were for Godwin, and all declared that they would live and die in his cause. Godwin and Harold had their chief station off the Isle of Wight, and they now determined to sail to London. As they advanced up the river, their forces still continued increasing, both by land and water. The peasantry supplied them with provisions, and all the country seemed to be at their command.

When the "earls" arrived in the port of London they transmitted their demands to the king. In appearance, their requests were sufficiently reasonable and just, since they confined their petitions to the restoration of their former territories and dignities. If Godwin and his family had not been liable to suspicion, such a proceeding would have indicated great moderation. But Edward considered it as fraught with danger; for he gave a peremptory denial, and his refusal excited so bitter a feeling against him amongst the troops of Godwin, that the old earl had great difficulty in restraining them, though at the same time he steadily pursued his own purpose, and succeeded in gaining over the burgesses of London and Southwark to his party. When all Godwin's men were assembled, he put himself in motion; and whilst his vessels sailed up the river, his land army assembled on the "Strand," then, what its name implies, an open shore, without the walls of London, and extending along the northern bank of the river Thames.

The king's forces were considerable. But, as before, they were extremely averse to civil war. They were loth to fight with their own kinsmen; Englishmen only were engaged on either side. If Edward had been worsted in battle, a revolution was to be apprehended, and the crown might have been transferred to the house of Godwin. And, under these circumstances, King Edward, however unwillingly, was compelled to yield to the wishes of his subjects, and to agree to a compromise. Offers were made by the king, sufficient to appease the resentment, and satisfy the ambition of Godwin and Harold. Edward submitted to their preponderance, and the treaty was concluded, like all important transactions, by means of the witenagemot. Godwin appeared before the "earls, and the best men of the land," who were assembled, and declared that he and his sons were innocent of the crimes which had been laid to their charge.

The great council not only agreed that Godwin and his sons were innocent, but decreed the restoration of their earldoms; and such was the influence of the Earl of Wessex, that the witan adopted all the views of his party. All the French were declared outlaws, because it was said that they had given bad advice to the king, and brought unrighteous judgments into the land; a very few only, whose ignoble names have been preserved—Robert the Deacon, Richard the son of Scrub, Humphrey Cock's-foot, and the Groom of the stirrup,—were excepted from this proscription: obscure, mean men, whom Godwin could not fear. Robert, the monk of Jumieges, who had been promoted to the Archbishopric of Canterbury, was just able to escape with his life, so highly were the people incensed against him. He and Ulf, Bishop of Dorchester, after scouring the country, broke out through the east-gate of Canterbury, and killing and wounding those who attempted to stop them, they betook themselves to the coast, and got out to sea. Other of the Frenchmen retired to the castles of their countrymen, and the restoration of the queen to her former rank, completed the triumph of the Godwin family.

A very short time after these events, Godwin died (A.D. 1053). We are told, that when he was banqueting with Edward at Windsor, words arose between them. Edward still believed that Godwin had been the guilty cause of Alfred's murder. "May this morsel be my last," said Godwin, "if I committed the crime;" and this imprecation was followed by his death, he being choked by the bread which he had attempted to swallow. I do not vouch for these particulars. Tradition has been busy with his memory. The shoals called the "Godwin Sands," are popularly considered as his estates, which being overflowed by the sea, became and are the terror of the mariner. The exact circumstances of Godwin's death are doubtful; and the more authentic chroniclers, omitting the other details, only state that he was struck speechless, and that he died miserably within three days. [ Poisoned? ]

Harold, as the eldest son of Godwin, succeeded to his father's

territories, and to his authority (A.D. 1053-1055). He vacated the earldom

of East Anglia, which was bestowed upon Algar, son of Leofric, who had held the

honour during Harold's outlawry. This appears to have been a device, enabling

him to quiet his opponents until he should gain more power; and his influence

rapidly increased. Upon the death of Siward, the doughty Earl of Northumbria,

the king appointed Tostig, Harold's brother, as his successor; but with little

justice, and contrary to the wishes of the people, and the right of Siward's

heir.

Harold gained much by the expulsion of Algar, who was outlawed by the

"witenagemot," upon the accusation of treason, but unjustly, and

without any real cause. Algar, trusting in the power of his father Leofric, who

was still able to counterbalance the influence of Harold, was not to be easily

disheartened. The stout exile imitated the example of Godwin and Harold under

similar circumstances, and appealed to the sword. Retiring to the dominions of

Griffith, King of Wales, who had espoused Algitha, his sister, and was then

waging war against Harold, they collected a large force, and, advancing upon

Hereford, burnt the city, and penetrated into Gloucestershire.

Here Algar and his allies were encountered by Harold; and after much bloodshed had been occasioned, peace was established between the competitors, the sentence of outlawry being reversed; and Algar was restored to his possessions and dignity. Some time afterwards, Leofric died, and the earldom of Cestrian-Mercia devolved upon Algar, who again falling under the displeasure of Edward, or rather of Harold, was outlawed and banished a second time. Algar was as bold as before; and, repairing to his old friends and allies, the Welsh, and assisted by a fleet of the Danes, he recovered possession of his earldom by main force, defying Edward and his power. A greater affront was offered to King Edward by the Northumbrians, who, rising against Tostig, slew his retainers, seized his treasure, and expelled him from the earldom, and, electing Morkar, a son of Algar, as their earl, demanded that assent from Edward which he could not refuse.

A kingdom in which such events could take place, was evidently on the verge of ruin. Neither confidence nor unanimity subsisted. Faction was contending against faction; and, like the Britons of the old time, every bystander must have seen that the realm was at the mercy of any invader. During these transactions, old age was rapidly advancing upon Edward. I have told you he was childless. He saw the increasing power of Harold, and that the kingdom which he had been called to govern, would be exposed to the greatest confusion. Upon the decease of Edward, the only representatives of the line of Cerdic would be found in the descendants of Edmund Ironside (A.D. 1057). King Edward had hitherto regarded his family with coldness, if not with aversion. But the wish to ensure tranquillity to his kingdom prevailed; and he recalled "Edward the Outlaw" from his abode in Hungary, with the intention of proclaiming him as heir to the crown.

Edmund Ironside had been much beloved, and greatly did England rejoice when Edward, no longer the Outlaw, but the Atheling, arrived here, accompanied by his wife Agatha, the emperor's kinswoman, and his three fair children, Edgar, Christina, and Margaret. But the people's gladness was speedily turned to sorrow. Very shortly after the Atheling arrived in London, he sickened and died. [Poisoned?] He was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral; and sad and ruthful were the forebodings of the English, when they saw him borne to his grave. Harold gained exceedingly by this event. Did the Atheling die a natural death?—the lamentations of the chroniclers seem to imply more than meets the ear.

Edward's design having thus been frustrated, he determined that William of Normandy should succeed him to the throne of England (A.D. 1058-1065), and he executed, or, perhaps, re-executed a will to that effect, bequeathing the crown to his good cousin. This choice, disastrous as it afterwards appeared to be from its consequences, was not devoid of foresight and prudence. Edward, without doubt, viewed the nomination of the Norman as the surest mode of averting from his subjects the evils of foreign servitude or domestic war. The Danish kings, the pirates of the north, were yearning to regain the realm which their great Canute had ruled. At the very outset of Edward's reign, Magnus, the successor of Hardicanute, had claimed the English crown. A competitor at home had diverted Magnus from this enterprise; but it might at any time be resumed. And how much better would the wise and valiant William be able to resist the Danish invasions, than the infant Edgar? Harold was brave and experienced in war, but his elevation to the throne might be productive of the greatest evil. The grandsons of Leofric, who ruled half England, would scarcely submit to the dominion of an equal; the obstacle arising from Harold's ancestry was indeed insuperable. No individual, who was not of an ancient royal house, had ever been able to maintain himself upon an Anglo-Saxon throne.

William himself asserted, that Edward had acted with the advice and consent of the great Earls, Siward, Leofric, and Godwin himself; consequently the bequest was made before the arrival of Edward the Outlaw. The son and nephew of Godwin, who were then in Normandy, had also been sent to him, as he maintained, in the characters of pledges or hostages, that the will should be carried into effect; or, as is most probable, that no opposition should be raised by the powerful earl. The three earls thus vouched, were not living when William made this assertion; but if we do not distrust his veracity and honour, we may suppose that Edward, in the first instance, appointed William as his heir. As the king grew older, his affection for his own kindred awakened, and he recalled the Atheling, revoking his devise to the stranger

....

Upon the death of Edward the Confessor, there were three claimants to the crown, his good cousin, William of Normandy, and his good brother-in-law, Harold—each of whom respectively founded their pretensions upon the real or supposed devise of the late king—and Edgar Atheling, the son of Edward the Outlaw, who ought to have stood on firmer ground. If kindred had any weight, he was the real heir—the lineal descendant of Ironside—and the only male now left of the house of Cerdic; and he also is said to have been nominated by Edward, as the successor to the throne.

Each of these competitors had his partisans: but, whilst William was absent, and Edward young and poor, perhaps timid and hesitating, Harold was on the spot; a man of mature age, in full vigour of body and mind; possessing great influence and great wealth. And on the very day that Edward was laid in his grave (Jan. 6, 1066), Harold prevailed upon, or compelled the prelates and nobles assembled at Westminster, to accept him as king. Some of our historians say, that he obtained the diadem by force. This is not to be understood as implying actual violence; but simply, that the greater part of those who recognised him, acted against their wishes and will. And if our authorities are correct, Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury, but who had been suspended by the pope, was the only prelate who acknowledged his authority.

Some portions of the Anglo-Saxon dominions never seem to have submitted to Harold. In others, a sullen obedience was extorted from the people, merely because they had not power enough to raise any other king to the throne. Certainly the realm was not Harold's by any legal title. The son of Godwin could have no inherent right whatever to the inheritance of Edward; nor had the Anglo-Saxon crown ever been worn by an elective monarch. The constitutional rights of the nation extended, at farthest, to the selection of a king from the royal family; and if any kind of sanction was given by the witan to the intrusion of Harold, the act was as invalid as that by which they had renounced the children of Ethelred, and acknowledged the Danish line.

Harold is stated to have shewn both prudence and courage in the government of the kingdom; and he has been praised for his just and due administration of justice. At the same time he is, by other writers, reprobated as a tyrant; and he is particularly blamed for his oppressive enforcement of the forest-laws. Towards his own partisans, Harold may have been ostentatiously just, while the ordinary exercise of the royal prerogative would appear tyrannical to those who deemed him to be an usurper.

Harold, as the last Anglo-Saxon ruler, has often been viewed with peculiar partiality; but it is perhaps difficult to justify these feelings. He had no clear title to the crown in any way whatever. Harold was certainly not the heir: Edward's bequest in his favour was very dubious; and he failed to obtain that degree of universal consent to his accession, which, upon the ordinary principles of political expediency, can alone legalize a change of dynasty. The Anglo-Saxon power had been fast verging to decay. As against their common sovereign, the earls were rising into petty kings. North of the Humber, scarcely a shadow of regular government existed; and even if the Norman had never trod the soil of England, it would have been scarcely possible for the son of Godwin to have maintained himself in possession of the supreme authority. Any of the great nobles who divided the territory of the realm might have preferred as good a claim, and they probably would have been easily incited to risk such an attempt. Hitherto, the crown had been preserved from domestic invasion by the belief that royalty belonged exclusively to the children of Woden. Fluctuating as the rules of succession had been, the political faith in the "right royal kindred" excluded all competition, except as amongst the members of a particular caste or family; but the charm was now broken—the mist which had hitherto enveloped the sovereign magistracy was dispelled—and the way to the throne was opened to any competitor.

All the places in HITCHIN which were not in Harold's hands in 1066 were held BY HIS 'MEN' (Hitchin is in Herfordshire)

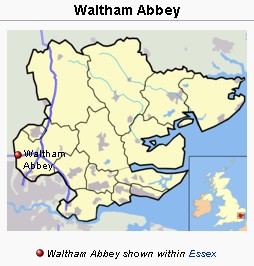

Waltham Abbey,

Essex - The name Waltham derives from weald or wald

"forest" and ham "homestead" or

"enclosure". The name of the ancient parish as a whole is Waltham

Holy Cross Waltham reverted to the King (Edward

the Confessor), who gave it to the Earl

Harold

Godwinson (later king). Harold rebuilt Tovi's church in stone around 1060,

in gratitude it is said for his cure from a paralysis, through praying before

the miraculous cross.

Waltham Abbey,

Essex - The name Waltham derives from weald or wald

"forest" and ham "homestead" or

"enclosure". The name of the ancient parish as a whole is Waltham

Holy Cross Waltham reverted to the King (Edward

the Confessor), who gave it to the Earl

Harold

Godwinson (later king). Harold rebuilt Tovi's church in stone around 1060,

in gratitude it is said for his cure from a paralysis, through praying before

the miraculous cross.

Legend

has it that after Harold's death at the Battle

of Hastings in 1066, his body was brought to Waltham for burial near to

the High Altar. Today, the spot is marked by a stone slab in the churchyard (originally

the site of the high alter prior to the reformation).

Legend

has it that after Harold's death at the Battle

of Hastings in 1066, his body was brought to Waltham for burial near to

the High Altar. Today, the spot is marked by a stone slab in the churchyard (originally

the site of the high alter prior to the reformation).

The grave of King Harold - see : Earl Godwin his son Earl Harold and his "Utlagh" men

Temple Dinsley firmly enters the historical record in the Domesday Book in 1086, when Deneslai is recorded as a manor previously belonging to King Harold.

King Harold Buried in the Village of Bosham?

For almost 1,000 years, the final resting place of King Harold has remained a tantalising mystery. As every schoolchild is told, the last Saxon monarch was reputedly killed with an arrow through the eye at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

But the body of Harold II, as he should formally be known, has never been found. After his defeat by the Normans, the king's body was hidden to prevent his tomb becoming a shrine to martyrdom. In fact, he is supposedly the only monarch since Edward the Confessor whose whereabouts remain a puzzle. Traditionalists believe he is interred at Waltham Abbey in Essex. But amateur historian John Pollock thinks a forgotten body underneath a parish church in West Sussex holds the secret. After his research, a parochial church council yesterday applied for human remains buried below the chancel arch at Holy Trinity Church, Bosham, to be unearthed.

Mr Pollock, who lives in the village, said: "I am absolutely convinced that it is Harold in there." The church already claims to be the final resting place of King Canute's daughter and the village is awash with seafaring tales and medieval myths ranging from a spooky bell heard at sea to hidden tunnels under the streets.

The church bones were inadvertently discovered in 1954 by workmen. They found a stone sarcophagus and a body with its head and part of a leg missing. DNA profiling was not available at the time and the tomb was covered over. But, having researched church records, Mr Pollock now believes this is Harold. Other legends, instead of describing the king being slain by an arrow, suggest he was beheaded and dismembered. He was said to have been buried near the sea and Bosham is also linked with the king, who is depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry visiting Bosham in 1064.

Harold Rex

Is King Harold II buried in Bosham Church (9781900851008) John Pollock Books

Bosham - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sussex Churches Bosham

- Bosham Church appears on the Bayeaux Tapestry in the scene where Harold leaves

England to travel to Normandy, stopping to pray in Bosham Church en route. It is

also traditionally the burial place of King Canute's daughter, and the King

himself may have been responsible for building the Saxon features that visitors

so enjoy seeing today.

Cnut the Great - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Edward the Confessor - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Godwin, Earl of Wessex - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Harold Godwinson - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hereward the Wake - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles - 1052 (Giles, 1847)

((A.D. 1052 . This year died Alfric, Archbishop of York, a very pious man, and wise. And in the same year King Edward abolished the tribute, which King Ethelred had before imposed: that was in the nine-and-thirtieth year after he had begun it. That tax distressed all the English nation during so long a time, as it has been written; that was ever before other taxes which were variously paid, and wherewith the people were manifestly distressed.

In the same year Eustace [Earl of Boulougne] landed at Dover: he had King Edward's sister to wife. Then went his men inconsiderately after quarters, and a certain man of the town they slew; and another man of the town their companion; so that there lay seven of his companions. And much harm was there done on either side, by horse and also by weapons, until the people gathered together: and then they fled away until they came to the king at Gloucester; and he gave them protection.

When Godwin, the earl, understood that such things should have happened in his earldom, then began he to gather together people over all his earldom, (75) and Sweyn, the earl, his son, over his, and Harold, his other son, over his earldom; and they all drew together in Gloucestershire, at Langtree, a great force and countless, all ready for battle against the king, unless Eustace were given up, and his men placed in their hands, and also the Frenchmen who were in the castle.

This was done seven days before the latter mass of St. Mary. Then was King

Edward sitting at Gloucester. Then sent he after Leofric the earl [Of Mercia]

and north after Siward the earl [Of Northumbria] and begged their forces. And

then they came to him; first with a moderate aid, but after they knew how it was

there, in the south, then sent they north over all their earldoms, and caused to

be ordered out a large forcefor the help of their lord; and Ralph, also, over

his earldom:

and then came they all to Gloucester to help the king, though it might be late.

Then were they all so united in opinion with the king that they would have

sought out Godwin's forces if the king had so willed.

Then thought some of them that it would be agreat folly that they should join battle; because there was nearly all that was most noble in England in the two armies, and they thought that they should expose the land to our foes, and cause great destruction among ourselves. Then counselled they that hostages should be given mutually; and they appointed a term at London, and thither the people were ordered out over all this north end, in Siward's earldom, and in Leofric's, and also elsewhere; and Godwin, the earl, and his sons were to come there with their defence.

Then came they to Southwark, and a great multitude with them, from Wessex; but his band continually diminished the longer he stayed. And they exacted pledges for the king from all the thanes who were under Harold, the earl, his son; and then they outlawed Sweyn, the earl, his other son.

Then did it not suit him to come with a defence to meet the king, and to meet the army which was with him. Then went he by night away; and the king on the morrow held a council, and, together with all the army, declared him an outlaw, him and all his sons.

And he went south to Thorney, and his wife, and Sweyn his son, and Tosty and his wife, Baldwin's relation of Bruges, and Grith his son.

And Harold, the earl, and Leofwine, went to Bristol in the ship provisioned. And the king sent Bishop Aldred [Of Worcester] to London with a force; and they were to overtake him ere he came on ship-board: but they could not or they would not. And he went out from Avonmouth, and met with such heavy weather that he with difficulty got away; and there he sustained much damage. Then went he forth to Ireland when fit weather came.

And Godwin, and those who were with him, went from Thorney to Bruges, to Baldwin's land, in one ship, with as much treasure as they might therein best stow for each man. It would have seemed wondrous to every man who was in England if any one before that had said that it should end thus; for he had been erewhile to that degree exalted, as if he ruled the king and all England; and his sons were earls and the king's darlings, and his daughter wedded and united to the king: she was brought to Wherwell, and they delivered her to the abbess.

Then, soon, came William, the earl [Of Normandy], from beyond seas with a

great band of Frenchmen; and the king received him, and as many of his

companions as it pleased him; and let him away again. This same year was given

to William, the priest, the bishopric of London, which before had been given to

Sparhafoc.))

...

((A.D. 1052 . In this year died Elgive Emma, King Edward's

mother and King Hardecanute's.

And in this same year, the king decreed, and his council, that ships should proceed to Sandwich; and they set Ralph, the earl. and Odda, the earl [Of Devon], as headmen thereto.

Then Godwin, the earl, went out from Bruges with his ships to Ysendyck, and left it one day before Midsummer's-mass eve, so that he came to Ness, which is south of Romney. Then came it to the knowledge of the earls out at Sandwich; and they then went out after the other ships, and a land-force was ordered out against the ships.

Then during this, Godwin, the earl, was warned, and then he went to Pevensey; and the weather was very severe, so that the earls could not learn what was become of Godwin, the earl. And then Godwin, the earl, went out again, until he came once more to Bruges; and the other ships returned again to Sandwich.

And then it was decreed that the ships should return once more to London, and that other earls and commanders should be appointed to the ships. Then was it delayed so long that the ship-force all departed, and all of them went home.

When Godwin, the earl, learned that, then drew he up his sail, and his fleet, and then went west direct to the Isle of Wight, and there landed and ravaged so long there, until the people yielded them so much as they laid on them. And then they went westward until they came to Portland, and there they landed, and did whatsoever harm they were able to do.

Then was Harold come out from Ireland with nine ships; and then landed at

Porlock, and there much people was gathered against him; but he

failed not to procure himself provisions. He proceeded further, and slew there a

great number of the people, and took of cattle, and of men, and of property as

it suited him. He then went eastward to his father; and then they both went

eastward until they came to the Isle of Wight, and there took that which was

yet remaining for them.

And then they went thence to Pevensey and got away thence as many ships as were there fit for service, and so onwards until he came to Ness, and got all the ships which were in Romney, and in Hythe, and in Folkstone.

And then they went east to Dover, and there landed, and there took ships and hostages, as many as they would, and so went to Sandwich and did "hand" the same; and everywhere hostages were given them, and provisions wherever they desired.

And then they went to North- mouth, and so toward London; and some of the ships went within Sheppey, and there did much harm, and went their way to King's Milton, and that they all burned, and betook themselves then toward London after the earls.

When they came to London, there lay the king and all the earls there against them, with fifty ships. Then the earls sent to the king, and required of him, that they might be held worthy of each of those things which had been unjustly taken from them.

Then the king, however, resisted some while; so long as until the people who were with the earl were much stirred against the king and against his people, so that the earl himself with difficulty stilled the people. Then Bishop Stigand interposed with God's help, and the wise men as well within the town as without; and they decreed that hostages should be set forth on either side: and thus was it done.

When Archbishop Robert and the Frenchmen learned that, they took their horses and went, some west to Pentecost's castle, some north to Robert's castle. And Archbishop Robert and Bishop Ulf went out at East-gate, and their companions, and slew and otherwise injured many young men, and went their way to direct Eadulf's-ness; and he there put himself in a crazy ship, and went direct over sea, and left his pall and all Christendom here on land, so as God would have it, inasmuch as he had before obtained the dignity so as God would not have it.

Then there was a great council proclaimed without London: and all the earls and the chief men who were in this land were at the council.

There Godwin bore forth his defence, and justified himself, before

King Edward his lord, and before all people of the land, that he was

guiltless of that which was laid against him, and against Harold his son, and

all his children.

And the king gave to the earl and his children his full friendship, and full earldom, and all that he before possessed, and to all the men who were with him.

And the king gave to the lady [Editha] all that she before possessed.

And they declared Archbishop Robert utterly an outlaw, and all the

Frenchmen,

because they had made most of the difference between Godwin, the earl, and the

king. And Bishop Stigand obtained the Archbishopric of Canterbury. In this same

time Arnwy, Abbot of Peterborough, left the abbacy, in sound health, and gave it

to Leofric the monk, by leave of the king and of the monks; and Abbot Arnwy

lived afterwards eight years. And Abbot Leofric then (enriched) the minster, so

that it was called the Golden-borough. Then it waxed greatly, in land, and in

gold, and

in silver.))

((A.D. 1052 . And went so to the Isle of Wight, and there took

all the ships which could be of any service, and hostages, and betook himself so

eastward. And Harold had landed with nine ships at Porlock, and slew

there much people, and took cattle, and men, and property, and went his way

eastward to his father, and they both went to Romney, to Hythe, to Folkstone,

to Dover, to Sandwich, and ever they took all the ships which they found,

which could be of any service, and hostages, all as they proceeded; and went

then to London.))

Notes:

(75)

Godwin's earldom consisted of Wessex, Sussex, and Kent:

Sweyn's of Oxford, Gloucester, Hereford, Somerset, and Berkshire: and

Harold's of Essex, East-Anglia, Huntingdon, and Cambridgeshire.

[ How interesting! Harold's Earldom is where we find many of the later

Utlagh's/Outlawe's ! Also the earlier land of the Wuffings]

Huntingdon - Huntingdon is a market town in the county of Cambridgeshire

in East

Anglia, England.

So - Why were the Godwin's Banished?

Edward the

Confessor - Harthacnut had been considered the legitimate successor following

Canute's death in 1035, but his half-brother, Harold

Harefoot, usurped the crown. Edward and his brother Alfred unsuccessfully

attempted to depose Harold in 1036. Edward then returned to Normandy, but Alfred

was captured by Godwin,

Earl of Wessex who then turned him over to Harold

Harefoot, who blinded him to make him unsuitable for kingship. Alfred died

soon after as a result of his wounds.

This murder of Edward's brother is thought

to be the source of much of Edward's later hatred for the Earl and one of the

primary reasons for Godwin's banishment in autumn 1051; Edward said that the

only way in which Godwin could be forgiven was if he brought back the murdered

Alfred, an impossible task

...

Godwin,

Earl of Wessex, who was firmly in control of the thegns

of Wessex, which

had formerly been the heart of the Anglo-Saxon monarchy; Leofric,

Earl of Mercia, whose legitimacy was strengthened by his marriage to Lady

Godiva, and in the north, Siward,

Earl of Northumbria. Edward's sympathies for Norman favourites frustrated

Saxon and Danish nobles alike, fuelling the growth of anti-Norman opinion led by

Godwin,

who had become the king's father-in-law in 1045. The breaking point came over

the appointment of an archbishop

of Canterbury. Edward rejected Godwin's man and appointed the bishop of

London, Robert

of Jumièges, a reliable Norman of Normandy.

...

Matters came to a head over a bloody riot at Dover between the townsfolk and

Edward's kinsman Eustace,

count of Boulogne. Godwin

refused to punish them, Leofric

and Siward

backed the King, and Godwin

and his family were all exiled in September 1051. Queen

Edith was sent to a nunnery at Wherwell.

Earl Godwin returned with an army following a year later, however, forcing the

king to restore his title and send away his Norman advisors. Godwin died in 1053

and the Norman Ralph

the Timid received Herefordshire,

but Godwin's son Harold accumulated even greater territories for the Godwin

family, who held all the earldoms save Mercia

after 1057. Harold

led successful raiding parties into Wales

in 1063 and negotiated with his inherited rivals in Northumbria in 1065, and in January

1066, upon Edward's death, he was proclaimed the king.

Robert of Jumièges - (sometimes Robert Chambert or Robert Champart, died between 1052 and 1055) was the first Norman Archbishop of Canterbury.[1] He had previously served as prior of the Abbey of St Ouen at Rouen in France, before becoming abbot of Jumièges Abbey, near Rouen, in 1037. He was a good friend and advisor to the king of England, Edward the Confessor, who appointed him Bishop of London in 1044, and then archbishop in 1051....The rift between Robert and Godwin culminated in Robert's deposition and exile in 1052.

Robert accompanied Edward the Confessor on Edward's recall to England in 1042[1] to become king following Harthacanute's death.[2] It was due to Edward that in August 1044 Robert was appointed Bishop of London,[14] one of the first episcopal vacancies which occurred in Edward's reign.[15] Robert remained close to the king and was the leader of the party opposed to Earl Godwin

Events came to a head at a council held at Gloucester

in September 1051, when Robert accused Earl Godwin of plotting to kill King

Edward.[31][notes

3] Godwin and his family were exiled; afterwards Robert

claimed the office of sheriff of Kent,

probably on the strength of Eadsige,

his predecessor as Archbishop, having held the office

...

Robert was declared an outlaw and deposed from his archbishopric on 14 September

1052 at a royal council, mainly because the returning Godwin felt that

Robert, along with a number of other Normans, had been the driving force behind

his exile.[22][44][notes

6] Robert journeyed to Rome to complain to the pope about

his own exile,[48]

where Leo IX and successive popes condemned Stigand,[49]

whom Edward had appointed to Canterbury.[50]

Robert's personal property was divided between Earl Godwin, Harold Godwinson,

and the queen, who had returned to court.[51]

When it became apparent that Godwin would be returning, Robert quickly left England[44] with Bishop Ulf of Dorcester and Bishop William of London, probably once again taking Godwin's son Wulfnoth and grandson Hakon (son of Sweyn) with him as hostages, whether with the permission of King Edward or not

Robert died at Jumièges,[52] but the date of his death is unclear. Various dates are given, with Ian Walker, the biographer of Harold arguing for between 1053 and 1055,[39] but H. E. J. Cowdrey, who wrote Robert's Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry, says on 26 May in either 1052 or 1055.[2][notes 7] H. R. Loyn, another modern historian, argues that it is likely that he died in 1053.[53]

Robert's treatment was used by William the Conqueror as one of the justifications for his invasion of England, the other being that Edward had named William his heir

So why Harold?

Edward's cousin's son, William of Normandy, who had visited England during Godwin's exile, claimed that the childless Edward had promised him the succession to the throne, and his successful bid for the English crown put an end to Harold's nine-month kingship following a 7,000-strong Norman invasion.

Edgar Ætheling was elected king by the Witan after Harold's death but was brushed aside by William. Edward, or more especially the mediæval cult which would later grow up around him under the later Plantagenet kings, had a lasting impact on English history.

Harold Godwinson - Marriages and children

For some twenty years Harold was married More

danico (Latin: "in the Danish manner") to Edith

Swannesha and had at least six children by her. The marriage was widely

accepted by the laity, although Edith was considered Harold's mistress by the

clergy. Their children were not treated as illegitimate.

According to Orderic

Vitalis, Harold was at some time betrothed to Adeliza,

a daughter of William, Duke

of Normandy, later William the Conqueror; if so, the betrothal never led to

marriage.[5]

About January 1066, Harold married Edith

(or Ealdgyth), daughter of Ælfgar,

Earl of Mercia, and widow of the Welsh prince Gruffydd

ap Llywelyn an enemy of the English. Edith had two sons — possibly

twins — named Harold and Ulf (born c. November 1066), both of whom survived

into adulthood and probably lived out their lives in exile.

After her husband's death, the queen is said[by

whom?] to have fled for refuge to her brothers Edwin,

Earl of Mercia and Morcar

of Northumbria but both men made their peace with the Conqueror initially

before rebelling and losing their lands and lives. Aldith may have fled abroad

(possibly with Harold's mother, Gytha, or with Harold's daughter, Gytha).

...

Harold's daughter Gytha

of Wessex married Vladimir

Monomakh Grand

Duke (Velikii

Kniaz) of Kievan

Rus' and is ancestor to dynasties of Galicia,

Smolensk,

and Yaroslavl,

whose scions include Modest

Mussorgsky and Peter

Kropotkin. Isabella

of France (consort of Edward II) was also a direct descendant of Harold via

Gytha, and thus the bloodline of Harold was re-introduced to the Royal

Line. Ulf, along with Morcar

and two others, were released from prison by King William as he lay dying in

1087. He threw his lot in with Robert

Curthose, who knighted him, and disappeared from history. Two of his elder

half-brothers, Godwine and Magnus, made a number of attempts at invading

England in 1068 and 1069 with the aid of Diarmait

mac Mail na mBo. They raided Cornwall as late as 1082, but died in

obscurity in Ireland.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/northernireland/ashorthistory/archive/topic25.shtml

Harold Godwinesson spent the winter of 1051-1052 in Ireland under

Dermot’s protection and after Harold had been defeated and killed at the

Battle of Hastings in 1066, his sons found refuge with this powerful

Irish High-King. ... When Dermot was killed in battle in 1072, he was

described by an annalist as the ‘King of Ireland with opposition’.

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/harold_of_wessex.htm

When Godwin was exiled in 1051, Harold went to Ireland where he stayed with the Dermont, King of Leinster

He married Eadgyth Swanneck and they had five children

The earls of Mercia and Northumbria remained loyal to the king and the Witan eventually declared that Earl Godwin and his sons had five days to leave England. Godwin and his sons, Tostig and Gyrth, joined Swegen in Flanders. Harold went to Ireland and spent the winter with Dermont, king of Leinster. The following year Harold sailed from Dublin with nine ships. After landing at Porlock in Somerset, Harold plundered the neighbourhood. He then joined up with his father and brothers and sailed up the Thames

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_of_Wessex

Edith of Wessex (c. 1029 – 19 December 1075) married King Edward the Confessor of England in 1045

Edith was the daughter of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, one of the most powerful men in England at the time of King Edward's rule. Her mother Gytha Thorkelsdóttir was sister of Ulf Jarl, and by tradition descended from saga hero Styrbjörn Starke and king Harold I of Denmark.

Upon Edward's death, on 4 January 1066, he was succeeded by Edith's brother, Harold Godwinson. At the Battle of Stamford Bridge (25 September 1066) and the Battle of Hastings (14 October

1066), Edith lost four of her remaining brothers (Tostig, Harold, Gyrth and

Leofwine). Her brother Wulfnoth, who had been given to Edward the Confessor as a

hostage in 1051 and soon afterwards became a prisoner of William the Conqueror,

remained in captivity in Normandy. Edith was therefore the only senior member of the Godwin family to survive the Norman conquest on English soil, the sons of Harold having fled to

Ireland.

Ireland's History in Maps (1100 AD)

Godwin family tree - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

Edith Swannesha |

|

Harold Godwinson | ||||||||||||

| Godwine (b. 1049) |

|

Edmund (b. 1049) |

|

Magnus (b. 1051) |

|

Gunhild (1055–1097) |

|

Gytha of Wessex (1053–1098) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Harold Godwinson |

|

Aldith of Mercia |

|

||||||||||||

| Harold (1067–1098) |

|

Ulf (1067–1087) | |||||||||||

thePeerage.com - Person Page 10670

Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó

- (died 7 February 1072) was king

of Leinster and a contender for the title of High

King of Ireland.

Diarmait belonged to the Uí

Cheinnselaig, a kin group of south-east Leinster

centred around Ferns.

Kings of Leinster were in a particularly advantageous position to exploit this new wealth as three of the five principal towns lay in or near Leinster. In Leinster proper, in the south-eastern corner dominated by the Uí Cheinnselaig, lay Wexford. To the west of this, in the smaller kingdom of Osraige, which had been attached to Leinster since the late 10th century, was Waterford. Finally, the most important Viking town in Ireland was Dublin, which lay at the north-eastern edge of Leinster.

The surviving sons of King Harold Godwinson of England escaped to Leinster after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 where they were hosted by Diarmait. In 1068 and 1069 Diarmait lent them the fleet of Dublin for their attempted invasions of England.

Harold Godwinson - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Ulf, along with Morcar and two others, were released from prison by King William as he lay dying in 1087. He threw his lot in with Robert Curthose, who knighted him, and disappeared from history. Two of his elder half-brothers, Godwine and Magnus, made a number of attempts at invading England in 1068 and 1069 with the aid of Diarmait mac Mail na mBo. They raided Cornwall as late as 1082, but died in obscurity in Ireland.

Wulfnoth Godwinson

- (1040 - 1094) was a younger brother of Harold

II of England, the sixth son of Godwin.

He was given as a hostage to Edward

the Confessor in 1051 as assurance of Godwin's good behaviour and support

during the confrontation between the earl and the king which led to the exile of

Godwin and his other sons. Upon Godwin's return to England at the head of an

army a year later, following extensive preparations in Ireland and Flanders,

Norman supporters of King Edward, and especially Archbishop Robert of Jumieges,

fled England. It is likely at this point that Wulfnoth (and Hakon, son of

Svein Godwinson, Godwin's eldest son) were spirited away by the fleeing

archbishop, and taken to Normandy, where they were handed over to Duke

William of Normandy

...

According to Eadmer's

Historia novorum in Anglia, the reason for Harold's excursion to

Normandy in 1064 or 1065 was that he wished to free Wulfnoth as well as his

nephew Hakon. To this end he took with him a vast amount of wealth, all of

which was confiscated by Count

Guy

I of Ponthieu when Harold and his party were shipwrecked

William may have held Wulfnoth as hostage against a resurgence of a remnant of Godwinson power. He stayed in comfortable, if not enviable, captivity in Normandy and later in England, and died in Salisbury in 1094, still a prisoner.

English

Resistance to the Normans 1067-1072

Or how the Normans conquered England

The Year 1068

In the north of England opposition began to grow to William as

it was told the king, that the people in the North had gathered themselves together, and would stand against him if he came. Whereupon he went to Nottingham, and wrought there a castle; and so advanced to York, and there wrought two castles; and the same at Lincoln, and everywhere in that quarter.

This show of strength seems to have been sufficient to quell the rebellion and Gospatric, who was Earl of Northumbria (having bought the earldom from William the previous year) and had presumably organised the 'gathering together', subsequently fled with his supporters into Scotland.

In the West Country there was further trouble as the sons of king Harold II, who are named by Florence of Worcester as Godwin, Edmund and Magnus arrived with a fleet at the mouth of the river Avon. They had previously fled to Ireland but now, in the summer of 1068, returned with a force of Hiberno-Norse mercenaries.

Their first target was Bristol, but the inhabitants successfully resisted, so they resorted to raiding the surrounding area. The brothers then left for Somerset, where they once again indulged themselves in a spot of pillaging. Here they were opposed by a local levy led by one Eadnoth Staller together with the local Norman garrisons. In the resulting conflict Eadnoth Staller was killed and possibly Magnus Haroldson as well. Despite taking some losses, the brothers seem to have got the better of the fighting and were able to return to Ireland with their loot.

The Year 1069

The year 1069 was to prove the crucial year in the course of the conquest as William I faced a number of simultaneous challenges to his rule.

The previous year William I had appointed Robert of Comines as Earl of Northumberia in place of Gospatric, but he was not a popular choice and whilst at Durham he was ambushed and killed togther with 900 of his men, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.(Or 700 according to Simeon of Durham or a mere 500 if you prefer Orderic Vitalis.) Edgar Aetheling, who had the previous year fled with his family and supporters to the relative safety of Scotland, took advantage of this display of resistance and left Scotland and,

came to York with all the Northumbrians and the men of the market town made peace with himWilliam rapidly marched north and surprised the Northumbrians and "ravaged the town and killed many hundreds of men" and recaptured York. For good measure he plundered the city; at *St. Peter's minster he made a profanation, and all other places also he despoiled and trampled upon

Edgar Aetheling fled back to Scotland where he was joined by more refugees.

Back in the West Country the sons of king Harold II returned. After the previous summers successful expedition Godwin and Edmund came once more with a fleet full of mercenary troops. They tried to capture Exeter this time but failed as the Normans had strengthened the city walls and built a castle and so returned to raiding Somerset and Cornwall. This time Brian of Penthievre organised an army against them and in a series of enagagments inflicted heavy losses on the brothers. They returned to Ireland and abandoned any further ideas of opposition to William I.

Faced with the news that her grandsons had failed to make any headway, Gytha abandoned Flatholm and sailed for Flanders and into obscrurity.

Unfortunately for William there was more trouble to come as the king of Denmark, Swein Estrithson arrived in the Humber esturary accompanied by his sons and his brother the Jarl Osbern, with a fleet of either 240 or 300 ships (the different versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle disagree on this point).

The appearance of large Danish fleet in the Humber was possibly the most significant challenge that William had yet encountered particularly as the Danes were soon joined by a number of native dissidents.

The Winchester Chronicle describes how the;

Prince Edgar and Earl Waltheof and Maerleswein and Earl Gospatric with the Northumbrians and all the people of the land riding and marching with an enormous raiding army, greatly rejoicing; and thus all resolutely went to York and broke down and demolished the castle and won countless treasures, and there killed many hundreds of Frenchmen

It was at this moment that Eadric the Wild together with his Welsh allies re-emerged from the hills and proceeded to attack and captured Shrewsbury and moved into Cheshire, where Chester was still holding out and refusing to recognise William I as king.

William advanced north to first counter the Danish threat. As he approached them the Danish fleet put to sea and began harrying the east coast. Satisifed that there was to be no organised move against London, William left part of his force behind to watch over the Danes and their allies and crossed the Pennines to meet the threat of Eadric.

There William I|William] was joined by Brian of Penthievre, fresh from his victory over the sons of Harold and together they defeated the combined force Welsh and marcher force at the battle of Stafford, although sans Eadric, who had scurried back to the safety of Wales some time before.

Having 'pacified' the western borderlands, William I|William] could now deal with the north, an issue that had become more pressing now that Hereward the Wake had began his revolt in the Fenland region of East Anglia. William I|William]therefore drove his army back across the Pennines to York and re-entered the city without opposition.

It was then that William carried out the notorious 'Harrowing of the North', when his army set out on an orgy of destruction, burning, looting and killing anything and everything they came across in the broad arc of territory between the Humber and the Wash; the Winchester Chroncile says that William "wholly ravaged and laid waste the shire" the Peterborough version simply says that he "completly did for it".

William paused to celebrate Christmas at York then spent the rest of the winter ravaging the Cleveland hills.

The year 1070

William's 'Harrowing of the North' a calculated act of political terrorism had its desired effect, as "This year Earl Waltheof made peace with the king". William,

gave the county of Northampton to earl Waltheof, one of the greatest of the English, and married him to his own niece Judith to strengthen the bonds of friendship between themaccording to Orderic Vitalis and was later to grant him the earlodum of Northumberland as well.

Gospatric too made a deal with William, and given that he still held the fortess at Bamburgh he was able to avoid any retribution for his opposition of the previous year.

With the revolt in Northumberland now silenced William once again crossed the Pennines with an army, his objective this time being Chester which stubbornly refused to recognise his authority. Despite difficulties with the weather, supplies and the mutiny of some of his French mercenary troops he arrived at Chester which promptly surrendered without a fight. Next according to Orderic Vitalis he suppressed all risings throughout Mercia with royal power.

The fall of Chester appears to have prompted Eadric the Wild to join the list of former rebels now making their peace with William I and two years later even joined William on his expedition of Scotland.

The threat of the Danish fleet remained however, and having over-wintered in the Humber. At the beginning of 1070 they established a base at the Isle of Ely and were joined by a mumber of local people including the famous Hereward the Wake. The appointment of a Norman bishop to the see of Peterborough seems to have meant that the city was now regarded as a legitimate target. The Danes and Hereward co-operated in an assault on Peterborough when the Danes stripped the cathedral of its valuables.

Although William made little headway in his attempts to dislodge the rebels from Ely, Swein Estrithson now appears to have decided that there was nothing more for him to gain in Britain and the two kings were now reconciled; "the Danes went out of Ely with all the aforesaid treasure, and carried it away with them."

The year 1071

William might have been reconciled with both Waltheof and Gospatric but the two sons of Aelfgar were still at large; as the Chronicle explains they "ran off and travelled variously in woods and open country". Morkar eventually joined Hereward the Wake at Ely, but Edwin was "treacherously slain by his own men"

The arrival of Morkar at Ely seems to have spurred William into action and he launched a combined naval and land based assault against Ely and was eventually able to storm the rebel base by means of a specially constructed causeway. The outlaws then all surrendered; that was, Bishop Aylwine, and Earl Morkar, and all that were with them; except Hereward alone, and all those that would join him, whom he led out triumphantly

Hereward was to remain an irritant for a few years to come, but was never again able to significantly challenge Norman rule in England.

Northern Martial Arts [Archive]

Because of their renowned martial prowess, tested in battle, Berserkers

were valued fighting men in the armies of Pagan kings. Harald Fairhair,

Norwegian king in the ninth century, had Berserkers as his personal bodyguard,

as did Hrolf, king of Denmark. The bear- warrior symbolism survives in the

present day in the bearskin hats

worn by the guards of the Danish and British monarchs. But despite their

fighting prowess, their religious duties were still observed. For example,

"Svarfdoela Saga" records that a Berserker postponed a single combat

until three days after Yule so that he would not violate the sanctity of the

gods.

The Ulfhednar wore wolf-skins instead of mail byrnies ("Vatnsdoela

Saga"). Unlike the Berserkers, who fought in squads, the Ulfhednar entered

combat singly as guerilla fighters. A wolf-warrior is shown on a

helmet-maker's die from Torslinda on the Baltic island of Oland. In Britain,

there is a carving on the eleventh-century church

at Kilpeck in Herefordshire showing a wolf-mask with a human head looking out

from beneath it. This may be a stone copy of the usable masks hung up on Pagan

temples, worn in time of ceremony or war. Similiar masks, used by shamans, serve

as spirit receptacles when they are not being worn. In his "Life" of

Caius Marius, Plutarch

describes the helmets of the Cimbri as the open jaws of terrible predatory

beasts and strange animal masks.

In medieval Scandinavia, housecarls (Old Norse: húskarlar, singular húskarl; also anglicised as huscarl (Old English form) and sometimes spelled huscarle or houscarl) were either non-servile menservants, or household troops in personal service of someone, equivalent to a bodyguard to Scandinavian lords and kings.

This institution also existed in Anglo-Saxon England after its conquest by the kingdom of Denmark in the 11th century. In England, the royal housecarls had a number of roles, both military and administrative; they are well-known for having fought under Harold Godwinson at the battle of Hastings. The original Old Norse term, húskarl, literally means "house man"; see also the Anglo-Saxon term churl or ceorl, whose root is the same as the Old Norse karl, and which also means "a man, a non-servile peasant"[1].

By the end of the 11th century in England, there may have been as many as 3,000 royal housecarls (the Þingalið)[15]. As the household troops of Harold Godwinson, the housecarls had a crucial role as the backbone of Harold's army at Hastings. Although they were numerically the smaller part of Harold's army, their superior equipment and training meant they could be used to strengthen the militia, or fyrd, which made up most of Harold's troops. Thus, the housecarls were positioned in the center, around their leader's standard, but also probably in the first ranks of both flanks, with the fyrdmen behind them [24].

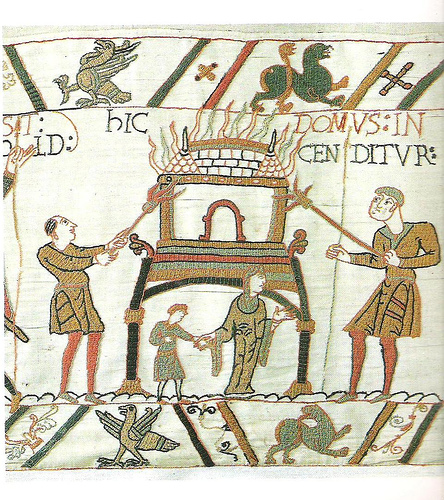

The Bayeux Tapestry depicts the housecarls as footmen clad in mail, with conical nasal helmets, and fighting with the great, two-handed Dane axe

Laurence J Brown - Housecarl (Conquest and Resistance, England 1066 to 1088)

The impression of many people, especially those not of English birth and

including a surprising number of history academics, is that that was that,

having lost their king, most of the nobility and the best fighting men, the

English then stopped resisting the Normans. Thus, they think, the Conquest,

as such, took effect immediately King Harold died. Nothing could be further from

the truth. From the rear guard action at the Battle of Hastings, know as the

Fight at the Fosse, where Norman casualties were higher than even those of the

main battle, to the final quenching of resistance some twenty years later, the

Normans knew little peace from their English subjects. Indeed has it ever ended?

Those who know the English class system with its continuous snipping would say

that the struggle against the 'Norman Yoke' continues to this day.

...

Although Ely fell in 1071, Hereward escaped and with a band of followers

remained a thorn in King William's side for many years to come.

Anglo Saxon 'Wulfnoth' meaning 'Wolf-daring' - “Wulfnoth” meaning “wolf boldness”

Wulfnoth Cild - (died 1015) was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman who is thought to have been the father of Godwin, Earl of Wessex and thus the grandfather of King Harold Godwinson. Earl Godwin's father was certainly named Wulfnoth, a relatively uncommon name. He is thus assumed to be the same person as Wulfnoth Cild, a thegn in Sussex.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that in 1009, Wulfnoth, commanding a force of 20 ships, was accused (of some unspecified offence) to King Æthelred the Unready by Earl Brihtric (or Beorhtric), Eadric Streona's brother. Wulfnoth retaliated by ravaging the south coast, leading to Brihtric being sent with a force of 80 ships to deal with him. Brihtric's ships were caught in a storm, driven ashore, and then burned by Wulfnoth and his men. Wulfnoth was sentenced to exile but his son Godwin remained in England.[1]

Wulfnoth's brother Æthelnoth became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1020.

The theory has been advanced by Alfred Anscombe in 1913 and more recently by D.H. Kelley that Harold Godwinson was descended through Godwin and Wulfnoth from King Æthelred via Æthelmær the Stout and Æthelweard the Historian (see link below).[2] The controversy is over whether Wulfnoth was the son of Æthelmær the Stout. There were at least two prominent men called Æthelmær at the time and it is often difficult to establish which one did which. Æthelmær the Stout was also known as "Cild of Sussex" and this line of ancestry is mentioned in the chronicle of John of Worcester.[3] However this is not mentioned in context of Harold's claim to the throne, nor did Godwin ever claim it for himself. However had he done so he might have been executed by Cnut instead of promoted — as was Æthelmær and his son Æthelweard II and various sons of Æthelred the Unready. The Dictionary of National Biography however, describe Godwin and Wulfnoth as parvenus of obscure origin. John of Worcester also describes Godwin as the son of a shepherd or swineherd,[4] perhaps contradictarily due to dual authorship. Godwin and Wulfnoth's alleged obscure origins have become part of accepted myth after 1066.

In 1014, the will of King Æthelred's son the Æthelstan Ætheling states that Godwin was to receive "the estate at Compton which his father possessed." This land was willed by Alfred the Great for the descendants of his elder brother Æthelred I and has been used by Professor David Hurmiston Kelley amongst others as evidence of Wulfnoth's descent from Æthelred.

Æthelmær the Stout's other son was Æthelnoth, who became Cnut's chaplain and later Archbishop of Canterbury (even though Cnut executed his brother). The circumstances of Wulfnoth's death are rather obscure, but occurred in 1015 at the same time as Cnut's takeover. Professor Frank Barlow refers to Æthelnoth as Godwin's uncle.[5] This descent would give Harold (and his brothers) a prior claim to the throne, even over the descendants of Alfred (since Æthelred was older than Alfred) but the BBC History website states that he had no claim.

Exeter - is a historic city in Devon, England.

In 1067, possibly because Gytha Thorkelsdóttir (Thorkel) , mother of King Harold, was living in the city, Exeter rebelled against William the Conqueror who promptly marched west and laid siege. After 18 days William accepted the city's honourable surrender in which he swore an oath not to harm the city or increase its ancient tribute. However, William quickly arranged for the building of Rougemont Castle to ensure the city's compliance in future. Properties owned by Saxon landlords were transferred into Norman hands, and on the death of Bishop Leofric in 1072, the Norman Osbern FitzOsbern was appointed his successor

Isle of Ely - Outlawe : Notice Thorkil ~= Ketel

1169 - Bromholm Priory - House of Glanville - Charter of Bartholomew de Glanville To Bromholme Priory - Walteri Utlage - Et duas partes decimarum meorum hominum: scilicet avunculi mei Rogeri de Bertuna: Et Galfridi presbiteri de Honinges: et Turstani despensatoris: et Warini de Torp: Et Ricardi Hurel: et Walteri Utlage: et Roberti de Buskevill: et decimam totam Ricardi filii Ketel