|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

I am starting a new page and concentrating on the Irish invasion connections to Pembroke(shire) . Also Strongbow first went about the region collecting men of fortune to go on the expedition to Ireland....

Reference: English Society in the Eleventh Century Essays in English Mediaeval History

| - - - - -

Ireland

under the Normans _Volume I

...

THE FIRST CONQUERORS 1167-9

It was in August 1167 that Dermot returned to Ireland from his exile. Though he did not

wait for Strongbow or Fitz Stephen, he did not come quite alone. He was accompanied

by a knight of Pembrokeshire named Richard Fitz Godebert (who appears to have been a

Fleming from Roch Castle, near Haverford), and a small body of troops.

Roch Castle

is a 13th century castle,

located near Haverfordwest,

Wales.

Roch Castle

is a 13th century castle,

located near Haverfordwest,

Wales.

Built by Norman knight Adam de Rupe in the second half of the 12th century,[1] probably on the site of an earlier wooden structure. Roche is the usual French word for Rock, while rupestre signifies a plant growing among rocks.[2]

Built at the same time as Pill Priory near Milford Haven, Roch Castle was probably built in this location as one of the outer defences of "Little England" or "Landsker", as it is located near the unmarked border for which centuries has separated the English and Welsh areas of Pembrokeshire

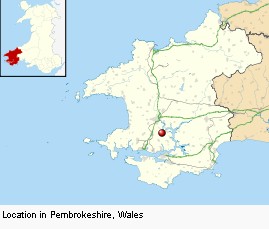

Pembrokeshire

- is a county in the south

west of Wales.

It borders Carmarthenshire

to the east and Ceredigion

to the north east. The county town is Haverfordwest

where Pembrokeshire County Council is headquartered.

Pembrokeshire

- is a county in the south

west of Wales.

It borders Carmarthenshire

to the east and Ceredigion

to the north east. The county town is Haverfordwest

where Pembrokeshire County Council is headquartered.

Much of Pembrokeshire, especially the south, has been English in language

and culture for many centuries. The boundary between the English and Welsh

speakers is known as the Landsker

Line. South Pembrokeshire is known as Little

England Beyond Wales.

...

Hwyel merged Dyfed with his own maternal inheritance of Seisyllwg, forming the new realm of Deheubarth.[4] The region suffered from devastating and relentless Viking raids during the Viking Age, with the Vikings establishing settlements and trading posts at Haverfordwest, Fishguard and Caldey Island.[4]

Dyfed, the region of Pembrokeshire, remained an integral province of Deheubarth but this was contested by invading Normans and Flemings who arrived between 1067 and 1111.[4] The region became known as Pembroke, after the Norman castle built in the Penfro cantref. But Norman/Flemish presence was precarious given the hostility of the native Welsh Princes. In 1136 Prince Owain Gwynedd to avenge the execution of his sister the Princess Gwenllian of Deheubarth and her children, with Gwenllian's husband the Prince Rhys swept down from Gwynedd with a formidable army and at Crug Mawr near Cardigan. There they met and destroyed the 3000 strong Norman/Flemish army. The remnants of the Normans fled across the bridge at Cardigan which collapsed and the Teifi river was choked with drowned Men at Arms and horses.

The Norman Marcher Lord Gilbert de Clare was also killed. Owains brother Cadwallader took de Clares daughter Alice as his wife. Owain incorporated Deheubarth into Gwynedd re-establishing control of the region. Mortally weakened Norman/Flemish influence never fully recovered in West Wales. Princess Gwenllian of Deheubarth is one of the best remembered victims.[5] In 1138 the county of Pembrokeshire was named as a county palatine

The county has long been divided between an English-speaking south (known as "Little England beyond Wales") and a historically more Welsh-speaking north, along an imaginary line called the Landsker.

The Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth, Princess Gwenllian's son, reestablished Welsh control over much of the region and threatened to retake all of Pembrokeshire, but died in 1197.[4] After Deheubarth was split by a dynastic feud, Llywelyn the Great almost managed to retake the region of Pembroke between 1216 and his death in 1240.

Little England beyond

Wales - The area was formerly part of the kingdom of Deheubarth,

but it is unclear when it became distinguished from other parts of Wales. B. G.

Charles gives a survey of the evidence for early non-Welsh settlements in the

area.[3]

The Norse

raided in the 9th and 10th centuries, and some may have settled, as they did

in Gwynedd

further north. There are scattered Scandinavian placenames in the area,

mostly in the Hundred

of Roose, north and west of the River

Cleddau.

...

The first explicit documentary evidence is that of Gerald

of Wales and Brut y Tywysogyon, which record that "Flemings"

were settled in south Pembrokeshire soon after the arrival

of the Normans in the early 12th century. Gerald says this took place

specifically in Roose.

Chepstow Castle

- located in Chepstow,

Monmouthshire

in Wales, on top of cliffs overlooking the River

Wye, is the oldest surviving post-Roman stone fortification in Britain.[1]

Its construction was begun under the instruction of the Norman

Lord William

fitzOsbern,[2]

soon made Earl

of Hereford, from 1067, and it was the southernmost of a chain of castles

built along the English-Welsh

border in the Welsh

Marches.

Chepstow Castle

- located in Chepstow,

Monmouthshire

in Wales, on top of cliffs overlooking the River

Wye, is the oldest surviving post-Roman stone fortification in Britain.[1]

Its construction was begun under the instruction of the Norman

Lord William

fitzOsbern,[2]

soon made Earl

of Hereford, from 1067, and it was the southernmost of a chain of castles

built along the English-Welsh

border in the Welsh

Marches.

Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (1st Creation) - Born 1130 Tonbridge, Kent, England

( Richard Fitz Gilbert de Clare founded the Priory of St Mary Magdalene in 1124 in Tonbridge and was an ancestor of Richard Fitz Gilbert a half brother of William the Conqueror)

Lord of Leinster, Justiciar of Ireland (1130 20 April 1176). Like his father, he was also commonly known as Strongbow (French: Arc-Fort). He was a Cambro-Norman lord notable for his leading role in the Norman invasion of Ireland.

Richard was the son of Gilbert de Clare, 1st Earl of Pembroke and Isabel de Beaumont. Richard's father died when he was about eighteen years old and Richard inherited the title Earl of Pembroke. It is probable that this title was not recognized at Henry II's coronation

As the son of the first Earl, he succeeded to his father's estates in 1148, but was deprived of the title by King Henry II of England in 1154 for siding with King Stephen of England against Henrys mother, the Empress Matilda.[2]

Richard was in fact, described by his contemporaries as the Earl of Striguil,

Striguil being where he had a fortress at a place now called Chepstow, in Monmouthshire on the Wye.[3] He saw an opportunity to reverse his bad fortune in 1168 when he met Dermot MacMurrough (Irish: Diarmait Mac Murchadha), King of Leinster.

| - - - - -

Striguil - or Strigoil is the name which was used from the 11th century until the late 14th century, for the port and Norman castle of Chepstow, on the Welsh side of the River Wye which forms the boundary with England. The name was also applied to the Marcher lordship which controlled the area in the period between the Norman conquest and the formation of Monmouthshire under the Laws in Wales Acts 15351542

The Marcher lordship of Striguil was established by William fitz Osbern, who started the building of the castle at Chepstow. On his death in 1071 the lordship passed to his son, Roger de Breteuil, but he plotted against King William, was captured and imprisoned, and had his estates forfeited. The lordship then reverted to the English crown until about 1115, when it was granted to Walter fitz Richard de Clare, the son of Richard fitz Gilbert. It remained with the de Clare family, including Richard de Clare known as "Strongbow", before passing to William Marshal on his marriage to Richard's daughter Isabel in 1189

| - - - -

Haverfordwest Castle

- Haverfordwest was believed to have been a Danish settlement prior to the

Norman conquest of West Wales in 1093/94

Haverfordwest Castle

- Haverfordwest was believed to have been a Danish settlement prior to the

Norman conquest of West Wales in 1093/94

The vast majority of sources indicate that the structure was originally a Norman architecture stone keep and bailey fortress, founded by the Englishman Gilbert de Clare, earl of Pembroke in 1120.[3][4] While this date is generally consistent, although some indicate 1110 or 1113,[5] Pembrokeshire Records insist that the castle was actually originally built by Tancred the Fleming, so the original medieval town and castle would have been Flemish not Norman and they claim that the castle remained in the possession of the Tancred family until 1210.[2] The original castle is believed to have been first attacked (unsuccessfully) by Gruffydd ap Rhys Prince of Deheubarth in 1135 - 1136. In 1173 the castle had its first royal visit by Henry II of England who passed by the town on coming back from a trip to Ireland.

| - - - -

Ireland under the Normans - Page 256

HENRY II IN IRELAND 255

(Henry lands in Ireland Oct 17, 1171)

On October 16, all being ready and the wind at last favourable, the king embarked ' at the

Cross ' below Pembroke, 2 and landed next day

at Crook, near Waterford, the exact landing- place being probably the ferry-point now called

Passage, about a mile from the old church of

Crook, 1 and five miles from Waterford. His army consisted of five hundred knights and their

esquires, and a large body of archers, about 4,000

in all. 2 A fleet of 400 ships was required to transport the men with their horses, arms, and

provisions. 3 Among the knights who accompanied

Henry were William FitzAudelin, the king's dapifer, Humphrey de Bohun, his constable,

Hugh de Lacy, Robert Fitz Bernard, sheriff of Devon, and Bertram de Verdun. 4

4 This list is given in the Song of Dermot, 11. 2601-10. According to the Gesta Hen. and Rog. Howden (ut supra)

,

William Fitz Audelin and Robert Fitz Bernard had been sent to Ireland some time before and met Henry at

Waterford. But we find both of these individuals witnessing a charter at Pembroke on October 7, 1171 (Round's

Commune of London, p. 152), so that at most they can only

have preceded the king by a few days. To the above list we may add from the witnesses to Henry's Dublin

charter,

William de Braose, Reginald de Curtenay, Hugh de Gunderville, Randulph de

Glanville, Hugh de Cressy , and Reginald de Pavilly ; and from Henry's charter to Hugh de Lacy, William

de Albiny, William de Stoteville, Ralph de Verdun, William de Gerpunville (the king's falconer), and Robert de Ruilly.

A topographical history of the county of Leicester - Rev. John Curtis

SHERIFFS, For the Counties of Leicester and Warwick, down to the 9th of Elizabeth, (the two counties having been under one charge from the reign of Henry II. until that period), and the list for this county continued to the present time.

1171-80 Bertram de Verdun.

1181 Randolph de Glaniville and Bertram de Verdun.

1182 Randolph de Glanville, Bertram de Verdun, Arnulph de Barton, and Adam

Aldelega.

1183 Randolph de Glanville, Adam de Audeley, Bertram de Verdun, and Arnnlph de Barton.

1184 Arnulph de Barton.

1185 Randolph de Glanville and Bertram de Verdun.

1186 Randolph de Glanville and Michael Beler.

1250 - William le

Utlag - Agmodesham - Buckinghamshire - The hundred of Burnham - Amersham

- 34 Henry III

1250 - (William)

- Willelmum le Utlag - Close Rolls, January 1250 - Henry III

Close rolls of the reign of Henry III preserved in the Public Record Office

1250. As for the wines carrying. - The mandate of the guards of the kings wines

- Suhampton, "as concerning the prises of forty tuns of wine which are in the custody of their own, and by the bailiffs of the king And the king of Suhampton 'acquietari he gave this order to the king, let them deliver the same bailiffs, for transporting them, which the king enjoined. Witness the King at Guldeford 'on the second day of January.

Concerning the men of Agmodesham to take up for the death of a man. -

The command is the sheriff of Buckingham, "as William Colebrond

'de Aumedesham, Robert Law, and William le Utlag', and the Elias Barleg 'to cause to come as far as London, so he set the sea on the Monday next after the feast of the Epiphany which is there the lord,

to answer for the death of William le Slee Johamiis of Puteham, whence he calls them. Witness as above.

34 Henry III

The hundred of Burnham - Amersham A History of the County of Buckingham Volume 3

Calendar of Ormond Deeds Vol. I. 1172-1350

1290 - Hugh de Utlaghe - Rosponte, New Ross Ireland - Adam Lagheleis son and heir of William Lagheleis grants to John son of Henry and his heirs in fee, a virgate in the vill of Nova pons [Rosponte, New Ross] in the street behind Market street, between the land then Hugh de Utlaghe's on the east and grantor's land on the west; paying yearly a clove gillyflower at Easter and to the chief lord 4^. silver. - Witnesses : Philip Beautur, seneschal of Rosponte, William de Branford, William son of Henry, provost, John le Espicer, John Kempe, David Mey, William le Seneschal, Stephen le sergeant, Richard le ganter, Robert Brun, Robert the clerk. [Circa 1290.]

1309 - ORMOND DEEDS

Witnesses : Eustace le Poer, John Droill, Fulc de Fraxineto, knights ; William Utlawe of

Kilkenny, John le Blunt of Kilkenny, John de la Roche, John son of Hugh le Clerke, John Godyn of Kilkomy, John Rys and John de la Barre, clerk. Given at Knocktopher on the 2nd day of March, anno Domini MCCCVIII and in the 2nd year of reign of King Edward son of King Edward.

[March 2, 1309.] Seals in perfect order.

433.

Walter de la Haye, knight, quit-claims to Nigel le Brun, knight, the whole manor of

Knocktopher, of which he gave him seisin on the second day of March. Witnesses : as in Deed 432. Given at Knocktopher on the 3rd day of March, anno Domini MCCCVIII. [March 3, 1309. N.S.] Seal perfect.

434.

1308 - Witness

William Utlawe of Kilkenny - Quitlaim of the manor of Knocktopher Walter de la

Haye, knight

" Walter de la Haye, knight, to all to whom these presents may come, greeting. Whereas lately we remitted and by our letters patent quit-claimed to David de Baa the suit which he owed at our Court of Knocktopher together with the royal service which he owed therefor, and also made him free of wardships, marriages and relief/and did also enfeoff Richard fitz Eustace in three acres of land with their appurtenances within the said manor and similarly did remit and quit-claim to Odo fitz John the services which he owed me for two carucates of land in Corbaly within the said manor/and afterwards on the morning after the feast of St. David last past was examined by Sir Alexander de Bikenore, Treasurer of Ireland and locum-tenens of the the Chancellor of Ireland, Sir Nigel le Brun, knight, Escheator of Ireland, Sir John de Hothum, Baron of the Exchequer at Dublin, and William de Bourn, clerk of the Lord Justiciar of Ireland, in the presence of Eustace le Poer and John le Botiller, knights, and

Masters John Desloys, Henry de Raggeleye, William Utlawe of Kilkenny, John de la Barre,

John de Penbrok, Walter de Letton, William de Wanton, Robert de Rocheford, Geoffrey fitz Walter and. many others then present/, at which time I made the above quit-claims and enfeoffment to the said David, Richard and Odo of the above-said services and tenements/1, Walter, then before

the above-said Alexander de Bikenore and the rest, admitted and do now by these presents admit that I have made the said quitclaims and enfeoffment to David, Richard and Odo above after and against the seisin of our lord the King made upon the manor of Knocktopher for my arrears in which I was held to the King upon my last account returned to the Exchequer of Dublin/ which arrears wrere reckoned at £746. And in order more fully to explain and attest what I did as described above, I have caused these my letters patent to be made." " Given at Knocktopher on the 3rd day of March, anno Domini MCCCVIII and in the 2nd year of King Edward son of King Edward"

[1308. O.S.].

1342 - William son of William Outlawe grants to

Johanna, who was the wife of William Outlawe, and to William son of Richard le Blound eight marcates of rent, payable yearly for the whole life of the said Johanna from all the messuages, lands and tenements (of above William son of William Outlawe) in Kilkenny ; granting power to the same Johanna and William son of Richard to distrain on all the said messuages for the above rent as often as it shall in part or whole be in arrears. Given at

Kilkenny on Monday next after the feast of the Ascension in the 42nd year of Edward III.

[May 13, 1342.] Seal missing.

1362 - church of

Jerpoint,

Roger son of William Outlawe and Dauid son of John fitz Nicholas the advowson of the church of Fynel as above. Witnesses : Robert Marescall, cleric, Nicholas Syfert, cleric, Maurice Deuenys, William Ley and Thomas Broun of Higginstowne. Given at

Fynel on February i, in the 36th year of Edward III. [February i,

1362, N.S.]

Reference: The Great Red Book of Bristol - Bristol (England) Vol 2 - Google Books

Page 305:

Burgage Tenure in Medieval Bristol

Fourteenth Century (1300's)

William Outlaghe for Richard de la Corder'

William Outlaghe for tenement formely of Richard de la Corderia

The Great White Book of Bristol - Bristol (England)

I am looking at another angle I had not thought of before, The colonization of Iceland by the Vikings around 900 AD , Harald The FairHair (Norway) began his "unification" of the country creating many "Exiles" and "Outlaws" who left in their ships for safer places to live. So this maybe the proto origin of the "Utlagi" family. Iceland has it's own "outlaw" sagas that although were written in the Twelfth-13th century were written about the 10th.

700~1000AD - Útlagi

placed this stone in memory of Sveinn -Rune sm103 - Småland,

Sweden

990~1010AD - Utlage

raised this stone in memory of Öjvind, a very good thegn -

Rune vg62 - Ballstorp, Västergötland, Sweden

957 - Outlawe(s) Banished

for political offences to Ireland by King Edwy - St. Dunstan Banished

959 - Outlawe(s) Return to England "with many wolves

heads" under King

Edgar reigns - St. Dunstan returns - 1613

Visitation Legend

960 - King

Edgar general pardon in return for a certain number of wolves' tongues

from each criminal

During the years 800-1200, Iceland and Greenland were settled by the Vikings. These people, also known as the Norse, included Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, and Finns

The Norse peoples traveled to Iceland for a variety of reasons including a search for more land and resources to satisfy a growing population and to escape raiders and harsh rulers. One force behind the movement to Iceland in the ninth century was the ruthlessness of Harald Fairhair, a Norwegian King (Bryson, 1977.)

Greenland

Vikings

Greenland

Vikings

In 960, Thorvald Asvaldsson of Jaederen in Norway killed a man. He was forced to leave the country so he moved to northern Iceland. He had a ten year old son named Eric, later to be called Eric Röde, or Eric the Red. Eric too had a violent streak and in 982 he killed two men. Eric the Red was banished from Iceland for three years so he sailed west to find a land that Icelanders had discovered years before but knew little about. Eric searched the coast of this land and found the most hospitable area, a deep fiord on the southwestern coast. Warmer Atlantic currents met the island there and conditions were not much different than those in Iceland (trees and grasses.) He called this new land "Greenland" because he "believed more people would go thither if the country had a beautiful name," according to one of the Icelandic chronicles (Hermann, 1954) although Greenland, as a whole, could not be considered "green." Additionally, the land was not very good for farming. Nevertheless, Eric was able to draw thousands to the three areas shown in Fig. 15.

Three Outlaw Sagas - Three Icelandic Outlaw Sagas. The Saga of Gisli. The Saga of Grettir. The Saga of Hord. Translated by G. Johnston and A. Faulkes. Edited and Introduced by A. Faulkes.

The three sagas translated from Old Icelandic in this volume are all about Icelanders in the Middle Ages who lived and died as outlaws in the Icelandic

countryside. Like all other sagas of Icelanders, these three are anonymous, but

they were certainly written by Icelanders, probably in the west or north-west of

Iceland. It is likely that The Saga of Gisli was written in the first half of the thirteenth century, perhaps about 1230, and thus is part of the first flowering of 'classical' Icelandic sagas. The Saga of Grettir is quite a lot later, from the fourteenth century, probably from about 1320 and later than most other sagas of Icelanders. Indeed the most recent editor of the saga (Örnólfur Thorsson, 1994) suggests that it may be from as late as the end of the fourteenth century. The Saga of Hord (called Holmveria saga, 'the Saga of the Holm-dwellers', in the principal manuscript) is also a late saga, probably from the second half of the fourteenth century. These last two sagas were therefore written quite a long time after the Icelandic Commonwealth was ceded to the Norwegian Crown in 1262-3, possibly even as late as the time of the union of the Norwegian, Swedish and Danish crowns (1397); and also after translated Romances and Heroic Sagas (fornaldar sögur, Sagas of Ancient Time or Legendary Sagas) may be regarded as having to a large extent superseded Sagas of Icelanders as the primary expression of Icelandic identity and values.

The attitudes to outlawry in Iceland in these texts are interesting to compare with those in English outlaw traditions; the earliest surviving legends of Robin Hood are from the fifteenth century.

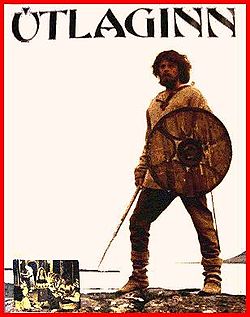

Útlaginn

(Outlaw: The Saga of Gisli) is an Icelandic

movie

filmed in 1981, detailing a blood

feud that took place in Viking

times. It is based upon one of the Icelanders'

Sagas called the Gísla

saga.

Útlaginn

(Outlaw: The Saga of Gisli) is an Icelandic

movie

filmed in 1981, detailing a blood

feud that took place in Viking

times. It is based upon one of the Icelanders'

Sagas called the Gísla

saga.

The film was released on 17 February 1984 to critical acclaim in Sweden,

and then in West

Germany. Written and directed by Ágúst

Guðmundsson, the theatrical version of the Saga of Gisli Sursson is said to

be an extremely culturally accurate representation of the peoples of the time

period.

...

This movie follows the story of Gisli, his family, and his adventures as an

outlaw included in the thirteenth century Icelandic

saga entitled Gísla

saga (Gisli Surssons Saga). The events take place from

940-980, but the saga itself was written around 1270-1320. Two written

versions of the saga exist, one of which is translated by Martin S. Regal.

However, there are slight deviations throughout the film. The role of Gislis

dreams seems unimportant throughout the course of the film until the final

battle between Gisli and his hunters, but in the saga his dreams played a bigger

role in predicting his fate. Also, the saga did not give faces to the women

portrayed in Gislis dreams. The film, however, depicts the good dream woman

as Gislis wife and the bad dream woman as his sister. This may have been done

in the film to ensure that the audience realized the critical roles that the

women played in the course of events in the story

| - - - - - - - -

Harald Fairhair

- (c. 850 c. 933), son of Halfdan

the Black, was the first king (872930) of Norway.

...

In 866, Harald made the first of a series of conquests over the many petty

kingdoms which would compose all of Norway, including Värmland

in Sweden, which had sworn allegiance to the Swedish king Erik

Eymundsson.

In 872, after a great victory at Hafrsfjord near Stavanger, Harald found himself king over the whole country. His realm was, however, threatened by dangers from without, as large numbers of his opponents had taken refuge, not only in Iceland, then recently discovered; but also in the Orkney Islands, Shetland Islands, Hebrides Islands, Faroe Islands and the northern European mainland.

However, his opponents' leaving was not entirely voluntary. Many Norwegian chieftains who were wealthy and respected posed a threat to Harald; therefore, they were subjected to much harassment from Harald, prompting them to vacate the land. At last, Harald was forced to make an expedition to the West, to clear the islands and the Scottish mainland of some Vikings who tried to hide there

History of Iceland

- The first permanent settler in Iceland is usually considered to have

been a Norwegian chieftain named Ingólfur

Arnarson. he settled with his family around 874, in a place he named Reykjavík

(Cove of Smoke) due to the geothermal steam rising from the earth.

...

Ingólfur was followed by many more Norse chieftains, their families and

slaves who settled all the inhabitable areas of the island in the next decades. These

people were primarily of Norwegian,

Irish and Scottish

origin. Some of the Irish and Scots were slaves and servants of the Norse chiefs

according to the Icelandic

sagas and Landnámabók

and other documents.... The traditional explanation for the exodus from Norway

is that people were fleeing the harsh rule of the Norwegian king Haraldur

Hárfagri (Harald the Fair-haired), whom medieval literary sources

credit with the unification of some parts of modern Norway during this period. It

is also believed that the western fjords of Norway were simply overcrowded

in this period.

...

In 930, the ruling

chiefs established an assembly called the Alþingi

(Althing). The parliament

convened each summer at Þingvellir,

where representative chieftains (Goðorðsmenn

or Goðar) amended laws, settled disputes and appointed juries to judge

lawsuits. Laws were not written down, but were instead memorized by an elected Lawspeaker

(lögsögumaður). The Alþingi is sometimes stated to be the world's

oldest existing parliament. Importantly, there was no central executive

power, and therefore laws were enforced only by the people. This gave rise to blood-feuds,

which provided the writers of the Icelanders'

sagas with plenty of material.

| - - - - -

Another aspect to this is that many "dispossessed" young men were recruited into the Christian religion ... Were the Utlagi exiles of King Edwy young monks of Saint Dunstan? and being of Viking ancestry fled to friendly viking Dublin Ireland?

OF SAGAS AND SHEEP:

TOWARD A HISTORICAL ANTHROPOLOGY OF SOCIAL CHANGE AND PRODUCTION FOR MARKET, SUBSISTENCE AND TRIBUTE IN EARLY ICELAND (10TH TO THE 13TH CENTURY)

by Jon Haukur Ingimundarson

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLGY

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA

1995

...

CHAPTER 9: A GOLD RING ON A BLOODY HAND. ON EPISODE THREE AND EPILOGUE OF BJARNAR SAGA HITDRLAKAPPA 242

...

The most common words for an outlaw in the family sagas are utlagi ("outlaw"; plural utlagar) and utilegumaour ("lying

out man"; plural utilegumenn) (Amory 1992). I will discuss the significance of Bjarnar saga's legalistic term for

outlaws in a moment.

...

The Icelandic family sagas do not make direct references to Icelandic cloisters and monks, which makes

sense since there were no monasteries in Iceland in the socalled "sagatime" (sogutimi), the period which is the family

stage (9th to the early 11th century).

The first cloisters in Iceland were established at ~ingeyrar (Southwest) in

1112, ~vera (Northwest) in 1155, and in Hitardalur in 1166-soon followed by the short lived monasteries on Flatey

island (1172-1184), about which little is known, and in 1181, the long-lasting, influential and literary-productive

Helgafell monastery. The last two mentioned monasteries were situated near Hitardalur to the north.

My idea that Bjarnar saga's evokes the knowledge of cloister-life in Hitardalur is not simply based on the

reference to virki. Bjorn's skogarmenn, who built the virki, calls forth the term

utlagi ("outlaw" or "outlying"),

with its multiple meaning assignments. It is possible that a saga writer, perhaps a

clergyman, replaced ultlagar--the

term Icelandic oral tales and family sagas use--with the legalistic skoqarmenn, when recording or putting together

the numerous tales about Bjorn Hitdaelakappi. The use of the word skogarmenn in place of

ultlagar leads to less direct

blasphemous comparison and identification of monastics with outlaws, i.e. a blasphemous portrayal of monastic persons,

their peculiar perceived roles in society, humble dispossessory backgrounds, and evasive status with respect

to secular/civil law.

In any case, I am interested in the concept of the "outlaw" as storytellers applied it for their subversive

depiction of social categories (perceived as anti-social in some sense) other than skogarmenn, i.e. the

men who by a

legal judgement at althing were expelled from the country, or were forced to live in hiding and sometimes as killers for

hire--see Amory 1992). I will argue that the outlaw representation of those who built Bjorn's virki and stayed

with him puts the finger on a disguised intelligent analysis of certain facts about the life and status of monastics in

an Icelandic farming community.

In her book Culture and History in Medieval Iceland, Kirsten Hastrup notes about conceptual structures an

equation between the law (log) and society, and an opposition between 'the social',or the 'inside', and 'the

wild', or the 'outside'. "Outlaws were absorbed into 'the wild', actually and conceptually," she says (1985:142). She

points out that log (the law) derives from leggja (to lay down), so law was what was 'laid down' (1985:11).

Therefore, according to Hastrup, utlagar were conceptualized both as 'lying out' in the wild and outside the law or

society.

...

I will therefore elaborate on Hastrup's analysis of medieval Icelander's "conceptual structures," with regard to 'outside' vs. 'inside', law equals society/community, and the position of

utlagi. I will make the argument that creators of Bjarnar saga applied the concepts utlagi (outlaw) and

utlaegur (outlawed) creatively--in order to convey ironic messages and express their critical social analysis.

First it should be said that storytellers must have been aware of the social fact that influential, affluent or

well connected individuals who committed serious transgressions against the law/society might not receive the

punishment of becoming full outlaws. On this, Bjarnar saga provides a example: when ~6r&ur and Kalfur

escape the

punishment of full outlawry, because they were able to pay a hefty fine instead, and because the powerful ~orkell

Eyj6lfsson's condition before the judgement was that his friend ~6r~ur should be

allowed to able to pay for his crime

by way of "wealth-payment" (fegjald), instead of being forced to leave the

country. In agreement with the above

observation and social fact was the realization that individuals would become legal outlaws only if they had

always been outlaws in another, non-legalistic sense, i.e. individuals who were without substantial alliance support,

those who were dispossessed, disinherited or excluded in one way or another from (while living within) community/society.

Now, my main concern is to show that monastic figures, including Bjorn, are depicted as outlaws in Bjarnar saga.

The very existence of ecclesiastics, monks in particular, invited storytellers to apply a cynical understanding of

"outlaw" and "outlawry" in order to describe, analyze, and explain their origins, statuses, and peculiar positions

within Icelandic farming communities. For one thing, it must have been observed that

a number of clergymen and monks

rose from the class of the lower peasantry, had been disinherited, or were illegitimate

children. In resemblance

to the legal utlagi, they were to leave their farm and family of origin, worldly community, and abandon possessions

and their former intimates. Of course, as I have pointed out earlier, ecclesiastical establishments must have been

quite integrated into, instead of isolated from the surrounding community of farming households. But similarly,

in spite of their received sentence, many outlaws would remain in hiding in Iceland, with intimates who aided and

harbored them, or district leaders who used their services as part of fulfilling their political ambitions (Amory

1992).

The use of a figure of "outlaw" to represent monastics in Bjarnar saga is clearly contingent on the observation

that "God's servants" (bj6nar drottins) did not view themselves as having to answer to secular authority, a

living within the framework of civil law/ordinary society.

Comparing monastics to outlaws was inspired by the fact that outlaws who did not leave Iceland, survived by acting outside the framework of secular law, and often performed,

as Amory suggests, "dirty deeds" (illvirki) on the behalf of politically-powerful families (who had the law in their own

hands) in return for material support and protection.

Thus I have built an argument for the analysis that the sk6garmenn who, according to rumor, built

Bjorn's fortress

refer to monks who performed services which Bjorn preceded over while he protected them. Bjorn's obscure men or

servants were in fact cloaked in two senses of that word (in cowls and under veil).

The making of a fortified circle

around Bjorn's farm at H6lmur, and his dominance within this circle or religious order--where he is portrayed,

interestingly enough, with a company thirty armed men over one Christmas celebration--marks the beginning of the end

for Bjorn. Since the mass on second day of Christmas is sung at H6lmur, we can read between the lines that Bjorn has

abandoned the church at Vellir in favor of another type of holy establishment at H6lmur, a fortified one. Bjorn has

made the transition from being a consecrated churchwarden to an obscure abbot and prior.

The use of the legal term for outlaws to describe Bjorn's obscure resident followers stems from the fact that members of monastic orders--unlike the

clergymen on private church farms--in some ways stood protected from the secular law code, outside the borders of

ordinary society. At the same time, Bjorn's "outlaws" reside inside a protective circle, the circular fortress;

they are the ultimate insiders who live outside the law and above the society.

| - - - - -

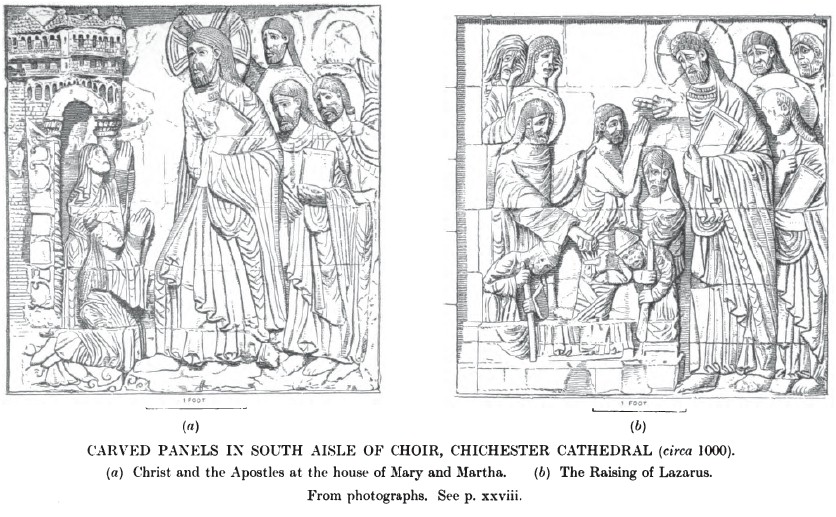

So here is more evidence that St. Dunstan was recruiting young monks for the clergy - for good or bad, he brought the Benedictine order to England under the reign of King Edgar. Priests stripped of wife and family would be completely dependent upon the church and would be much more obedient to Rome. Interestingly, this was still not enough for Rome. In 1066, William the conqueror was given permission from the Pope to invade England and with him he brought Norman priests even more loyal to the pope (William was borrowing money from everyone even the Pope/Lombards). Also another example of Britains' early worship of Mary Magdalene and Lazarus prior to the crusades (This was a Norman church built just after the conquest and prior to the crusades (and against the Cathars), The Normans of France certainly had exposure to the Cathars of Provence, France.

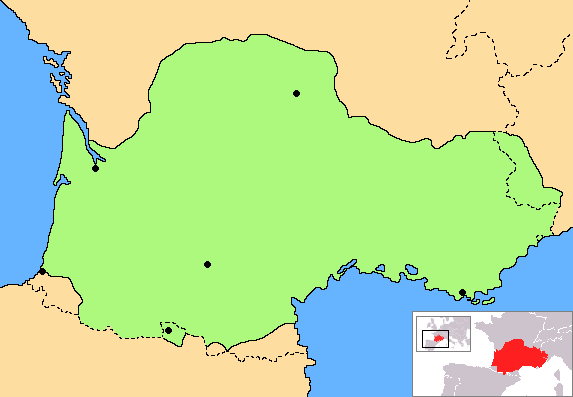

The Cathers Language: Occitan language is a Romance language spoken in southern France, Italy's Occitan Valleys, Monaco, and Spain's Val d'Aran: the regions sometimes known unofficially as Occitania. It is also spoken in the linguistic enclave of Guardia Piemontese (Calabria, Italy). Related - The Cat People: Catalan language

Linguistic

map of Occitania

Linguistic

map of Occitania

Notice also that Glastonbury was occupied with priests from Ireland:

The collected historical works of Sir Francis Palgrave

Chichester Cathedral - The Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, otherwise called Chichester Cathedral, is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Chichester. It is located in Chichester, in Sussex, England. It was founded as a cathedral in 1075, when the seat of the bishop was moved from Selsey... Chichester Cathedral was built to replace the cathedral founded in 681 by St. Wilfrid for the South Saxons at Selsey. The seat of the bishop was transferred here in 10

Selsey was the capital of the South Saxons kingdom, possibly founded by Ælle. Wilfrid arrived circa 680 and converted the kingdom to Christianity, as recorded by the Venerable Bede.[22] Selsey Abbey stood at Selsey (probably where Church Norton is today),[23] and was the cathedral for the Sussex Diocese until this was moved to Chichester in 1075 by order of William the Conqueror

139

Dunstan, Abbot of Glastonbury, had, at an early period of his

life, been admitted into that ancient monastery, which was then also a school or

college. Glastonbury1 was principally filled

by Scots, or monks from Ireland.

...

The popes of Rome were, about this time, most earnest in compelling the celibacy

of the clergy. In the Anglo-Saxon empire, this regulation had never yet been

enforced upon the inferior orders of the hierarchy. The principle upon which

the prohibition was founded, arose from a mistaken application of passages of

Scripture, appearing, when separated from their context, to justify a

restriction, which, if imposed as a yoke upon men's consciences, was wholly in

contradiction to the spirit of the Gospel. Considered, however, as a matter of

discipline and expediency, there were reasons of policy which might then render

it in some degree advisable. In the middle ages, when all the institutions of

society had a strong tendency to the establishment of hereditary right, and when

there was little written law, any usage or custom which had subsisted for two or

three generations, easily acquired the validity of positive legislation. Lands

had been granted to the clergy for their maintenance. A married priesthood would

soon have degenerated into a caste of sacerdotal nobility, holding their lands

as a patrimonial inheritance by the nominal condition of serving at the altar, but neglecting, in

fact, every duty which they were charged to perform.

143 Benedictine Order

955-973

At an earlier period, this state of things had been sufficiently realized in Northumbria, to shew the nature and extent of the imminent danger by which the church was threatened. If the system had prevailed, the spiritual ministration of religion would have been debased, the temporal advantages resulting to the community from the establishment of Christianity would have been wholly destroyed; therefore, we can well suppose, that many thinking men, honestly anxious for the real interests of religion, would labour for the prevention of such an abuse. Most closely connected with this question of celibacy, was the introduction of the Benedictine rule among the monks of England1.

Before Dunstan's time, each congregation of recluses lived according to its own internal regulations, nor were the several monasteries consolidated into one community.

A Roman of the name of Benedict, a man of sincere piety, had introduced a new code into the monastery which he founded upon Monte Cassino, in the ancient territory of the Samnitesa. Amongst much that was trifling, it contained more that was well adapted to increase the utility of the monastic life, and to restrain its vices, being particularly adapted to prevent the cloister from becoming a nestling place of sloth and profligacy. These monasteries, upon the continent, had united into one corporation.

The Benedictines of Italy were members of the same body as the Benedictines of Gaul. They were exempted from the jurisdiction of the bishops, and placed under a "General" of their own; and they soon became the ready instruments of papal

ambition.

The great object sought by the popes was the suppression of the independence of the different national churches of Christendom; and the celibacy of the clergy became a party badgea pledge of submission to the Church of

Rome, if yielded,a token of hostility, if refused. And in this spirit of conquest did Dunstan, and those who co-operated with him, engage in the plans which they pursued.

The Scottish or Irish, and Pictish and British churches, though in communion with Rome, were still independent of the papal

see. The Anglo-Saxon church was more inclined towards subjection, and the Benedictine rule had been introduced at Glastonbury. Yet the opposition was very strong.

...

146

The married clergymen, who refused to separate from their wives, were driven out by main force. Some, perhaps, were bribed into compliance by the king's [ Edgar ] bounty. As soon as a body of monks was established in any given church, large and ample donations were bestowed upon the new colony.

Such of the old English monks as had not yet received the Benedictine rule, were induced to fraternize with Monte

Cassino, either by approbation of the real merits of the systemfor merits it certainly hador in order to conciliate the king. During the Danish invasions and the consequent troubles, many of the endowments of the monasteries had been seized or acquired by the nobles and other laymen. Edgar often succeeded in persuading these persons to restore the property, which they could not hold with a good conscience. In other instances, if a stubborn "thane" resisted the persuasions of the monarch, and had made up his mind to despise the anathemas denounced against the usurpers of church property, Edgar purchased the land with his own money, and restored it to the church.

By these means, before the close of the reign of Edgar, forty-eight opulent Benedictine monasteries of monks and nuns were established in Anglo-Saxon

Britain; and these subsisted until the era fatal to all similar foundations.

Back to Runes and Ogham:

Ogham links to Pembrokshire: There are some four to five hundred surviving ogham inscriptions throughout Britain and Ireland with the largest number appearing in Pembrokeshire

Ogham -- Ancient History Encyclopedia

One of the stranger ancient scripts one might come across, Ogham is also known as the Celtic Tree Alphabet. Estimated to have been used from the

fourth to the tenth century AD it is believed to have been possibly named after the Irish god Ogma but this is debated widely. Ogham actually refers to the characters themselves, the script as a whole is more appropriately named Beith-luis-nin after the order of alphabet letters BLFSN.

Description

The script originally contained twenty letters grouped into four groups of five. Five more letters were later added creating a fifth group. Each of these groups was named after its first letter.

There are some four to five hundred surviving ogham inscriptions throughout Britain and Ireland with the largest number appearing in

Pembrokeshire. The rest of the inscriptions were located around south-eastern Ireland, Scotland, Orkney, the Isle of Man and around the border of Devon and

Cornwall. Ogham was used to write in Archaic Irish, Old Welsh and Latin mostly on wood and stone and is based on a high medieval Briatharogam tradition of ascribing the name of trees to individual characters.

The inscriptions containing Ogham are almost exclusively made up of personal names and marks of land ownership.

Origin Theories

There are four popular theories discussing the origin of Ogham. The differing theories are unsurprising considering that

the script has similarities to ciphers in Germanic runes, Latin, elder futhark and the Greek alphabet.

The first theory is based on the work of scholars such as Carney and MacNeill who suggest that Ogham was first created as a cryptic alphabet designed by the Irish. They assert that the Irish designed it in response to political, military and/or religious reasons so that those with knowledge of just Latin could not read it.

The second theory is held by McManus who argues that Ogham was invented by the first Christians in early Ireland in a quest for uniqueness. The argument maintains that the sounds of the primitive Irish language were too difficult to transcribe into Latin.

The third theory states that the Ogham script from invented in West Wales in the fourth century BC to intertwine the Latin alphabet with the Irish language in response to the intermarriage between the Romans and the Romanized Britons. This would account for the fact that some of the Ogham inscriptions are bilingual; spelling out Irish and Brythonic-Latin.

The fourth theory is supported by MacAlister and used to be popular before

other theories began to overtake it. It states that Ogham was invented in

Cisalpine Gaul around 600 BC by

Gaulish Druids who created it as a hand signal and oral language. MacAliser

suggests that it was transmitted orally until it was finally put into writing in

early Christian Ireland. He argues that the lines incorporated into Ogham

represent the hand by being based on four groups of five letters with a sequence

of strokes from one to five. However, there is no evidence for MacAlisters

theory that Oghams language and system originated in Gaul.

...

BabelStone The Ogham Stones of the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man, situated midway between Ireland and Britain, has always been at a sea-faring crossroads, and over the centuries has been exposed to influences from many different cultures. This is well reflected in the relatively large number of monumental inscriptions that have survived on the island, which include both runestones and Ogham stones, exhibiting a mixture of Irish, British, Pictish and Norse influences.

| - - - -

Reference:

R. I. Page - Raymond Ian Page (25 September 1924 10 March 2012) was a British historian of Anglo-Saxon England and the Viking Age, and a renowned runologist who specialized in the study of Anglo-Saxon runes.

Runes And Runic Inscriptions (David Parsons-Carl T. Berkhout) (London-1998)

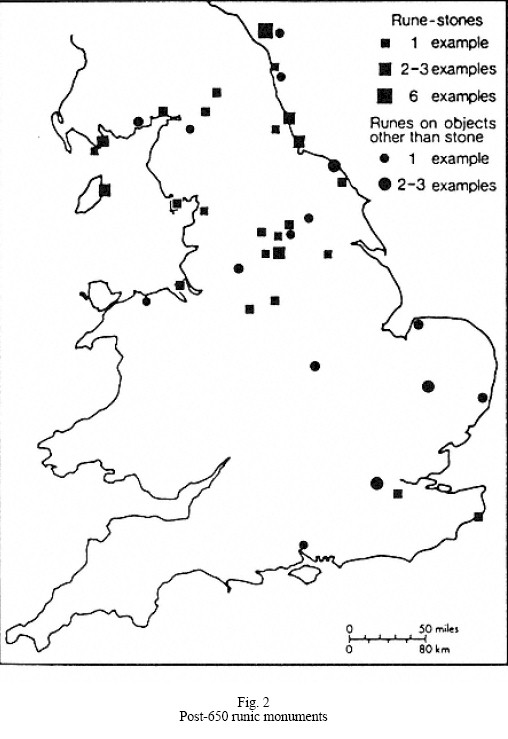

Our archaeologists and metal detectors continue to find new inscriptions with high frequency. The tentative distribution

maps I produced in 1973 showing inscriptions that could be clearly localised and dated before/after 650 were out of date

by 1987 when 'New Runic Finds in England' (below, pp. 27587) was published. That article is in turn outdated.55

Bringing the two 1973 maps up to the present produces figs 1 and 2. The pre-650 map is most dramatically changed,

with much fuller scatters of runes in East Anglia and the East Midlands and an outlier further north. East Anglia is also

more prominent in the post-650 map than it was in 1973, and it is obvious that this region must be given more attention

in any future discussion of English runes. What cannot be shown on any of these maps is the significance of the coin

evidence, for I do not know how that could be presented. Suffice it to point to the increased weight that new discoveries

have given to East Anglian and Kentish runic coins. Two considerations make the new maps no more definitive than

their earlier versions. (i) the dividing date of 650 is, as I have said, one of convenience rather than

principle. Above I

give examples of problems of setting close dates to English runic monuments. 650 seems to work as a dividing line, but

that is all that can be said for it. (ii) the maps remain tentative. For instance, I attribute three inscriptions to Brandon in

my later map but only two, I think, can be put clearly post-650. The third, on a bone handle, is included by association.

Again, I have not added the Worcester find to the later map though I suspect it properly belongs there. That might be

established in a formal excavation report. It would be an intriguing addition.

The past few years have brought an upsurge of interest in Anglo-Saxon runic studies, in part because of the entry to the

field of distinguished younger scholars. I hope the present collection helps by giving something of the background to

English runic research. The papers have been reprinted without major changes.

...

| - - - -

Add in the Ogham:

BabelStone - The Ogham Stones of Wales

Wales has the greatest number of Ogham stones of any region outside of Ireland (35 stones with definite Ogham inscriptions), but as can be seen from the map below, they are unevenly distributed, with large numbers in the south-west and the south-east, and only a handful in the north :

Location of Ogham stones and other Ogham-inscribed objects (England, Wales, Scotland and the Isle of Man are now complete; Ireland will be added by the end of Summer 2010.

Red tags mark the sites of

certain Ogham inscriptions (a dot indicates that the stone is in situ)

Yellow tags mark the sites of

dubious or unconfirmed Ogham inscriptions

Blue tags mark museums or

other sites where Ogham stone are held

Very important information about

early law "The All Thing" (Thing for All the land) and how a breech created a "wolf in the

sanctuary"

Notice the connection of "The Thing" to -> "All

Thing" -> Althing -> Atheling - a prince of any of the royal

dynasties .

Notice how both Runes and Ogham script is related to Greek alphabet and that Saxons were also Northmen that were considered remnants of Alexander the Greats' Greek Army. Alexander in his conquests went about collecting all the secret knowledge of the eastern conquests he could. The Hebrews may well have been liberated by Alexander from bondage of the Babylonians.

The Viking Age - the early history, manners and customs of the ancestors of the English-speaking nations - PAUL B. DU CHAILLU

The Viking Age- the early history, manners, and customs...

ORIGIN OF NAME ENGLAND. 19

That the history of the people called Saxons was by no means certain is seen in the fact that

Witikind, a monk of the tenth

century, gives the following account of what was then considered to be their origin 1 :

" On this there are various opinions, some thinking that the Saxons had their origin from the Danes and Northmen ;

others, as I heard some one maintain when a young man, that they are derived from the Greeks, because they themselves

used to say the Saxons were the remnant of the Macedonian army, which, having followed Alexander the Great, were by

his premature death dispersed all over the world."

...

In the Sagas the term England was applied to a portion only of Britain, the inhabitants of which were called

Englar,

Enskirmenn. Britain itself is called Bretland, and the people Bretar.

...

[The Promises to the Fathers - Truth in History

- Now Bret-land means literally covenant-land, or the land

of the covenant, as Britain means the island of the covenant. Here are two

witnesses in the ancient names of this land indicating that it is the land of

the covenant promised for the planting of Israel in the covenant which God made

with David, and the island of the covenant according to the descriptions

of the islands in the west at the ends of the earth as given by Isaiah. But,

in addition to this, consider the following truths: The Hebrew word for man is

ISH. Hence BRIT-ISH means literally covenant-man, or man of the covenant. The

islands to the northwest of Britain are called Hebrides to this day. Why? How

did they get that name? The simple and rational explanation is that they were

settled and named by the Hebrews. ]

It is an important fact that throughout the Saga literature describing the expeditions of the Northmen to England

not a

single instance is mentioned of their coming in contact with a people called

Saxons, which shows that such a name in Britain

was unknown to the people of the North. Nor is any part of England called Saxland.

OUTLAWRY. 578

Irredeemable crimes Outlaws regarded as enemies of society Custom of pleading for an outlaw Liabilities of a murderess Substitution of

corporal punishment and fines for outlawry Purchase of an outlaw's peace.

THE laws did not aspire to improve the moral condition of the criminal and try to make him a better man, except through

fear of punishment ; their object in early days was to prevent private revenge, and stop people taking matters into their own

hands. Crimes against personal rights or those of property were punished by fines as indemnity to the injured.

By paying

an indemnity the criminal released himself from the revenge of the injured and of his family, or from the outlawry which his

conduct or crime had brought upon him.

If any man had wronged another he was placed outside the pale of the law until the weregild was paid ; and if he or his

family could not pay he was outlawed, and the outlawry was declared at all the Things in the country.

...

BUYING PEACE FROM THE KING. 583

If a man was outlawed he had to buy his peace, "fridkaup," from the king, who determined what the amount should be.

[ Notice This allows an Outlaw who is a "friend" of the King to be above all - protected ]

" Now it may happen that the king permits the outlaw to stay in the land at the entreaties of chiefs, or in some other

way. Then he (the outlaw) must buy peace with the king according to his mercy (the price paid by the outlaw to stay

in peace in the country is determined by the king), and pay that half of his fine which is unpaid with sale-meetings

(auctions), of the kind that men of good sense see that he is well able to hold. If he is not willing to pay, the kinsmen of

the dead may take revenge on him, even though he be reconciled (in peace) with the king, and they will not be

outlawed though they slay him. But those who took care of his property while he was an outlaw must pay him back as

much as they received in lands and movables, and the rent of the land besides " (Frostathing's Law, Introd. 5).

SACREDNESS OF TEMPLES. 359

...

The temples were considered so holy that any one damaging them or entering them armed was declared an outlaw, and

no one who had committed an offence punishable by law was allowed to enter ; such person was called Vary i Veum (wolf

in the sanctuary). The grove or fields surrounding the temples were often regarded as inviolate, so that no act of

violence would be permissible within their precincts. This was expressed by the ancient name of Ve (sanctuary, sacred

place), which was extended so as to embrace the T/m^-place, which was also regarded as sacred, while the Thing was

going on.

THE THING . 515

The Thing was held in an open place called Thingvoll (Thing-plain), in earlier times

near a temple. 1 On the Thingvoll, or near it, there always seems to have been a

Thing-brekka, or Thing-hill, from which all announcements were made.

The Thing-plain was a sacred place, which must not be sullied by bloodshed arising from blood-feud (lieiptarblod) or

any other impurity. The Thing, from the time it was opened until it was dissolved, was during pagan times under the

protection of the gods. It was opened with certain religious ceremonies, which included a solemn peace declaration (grida

seining) over the assembly, which in earlier times was pronounced by the Hersir near whose temple the Thing took

place. Every breach of the peace at a Thing was a sacrilege which put the guilty one out of the pale of the law he was

like the violator of the temple peace a varg i veum (wolf in the

sanctuary), an outlaw in all holy or inhabited places, and an utlagi (outlaw) for all until he had made reparation

for his crime.

Reference: Anne-Christine-Larsen-the-vikings-in-ireland.pdf

The Vikings in Ireland - Anne-Christine Larsen

- Viking Ship Museum, Dec 30, 2001 - 172 pages

This compilation of 13 papers by scholars from Ireland, England and Denmark, consider the extent and nature of Viking influence in

Ireland. Created in close association with exhibitions held at the National Musem of Ireland in 1998-99 and at the National Ship Museum in Roskilde in 2001, the papers discuss aspects of religion, art, literature and placenames, towns and society, drawing together thoughts on the exchange of culture and ideas in

Viking Age Ireland and the extent to which existing identities were maintained, lost or assimilated.

In the late 12th-century Dublin roll of names Scandinavian personal names only make comparatively rare

appearances. Among those to appear most frequently are a number of compound names

in Thor-: Turold, Turbeorn, Torpin (Thorfin), Thur -got, Turkil, Thurstein and the short form Toki.

All

these names were also in common use in the Nordic homelands. The only signs of Irish-Nordic creative

initiative among the names in the Dublin roll are the forename Iarnfin, an otherwise unrecorded

compound, and the by-names Utlag outlaw, borne by Torsten and

Reginaldus, and the partially anglicised Vnnithing undastard, borne by

Philippus.

---- >>> Back to Outlawe Research Journal - Page 5